Rev. Adam Rankin of Lexington, Fayette County, Kentucky is the source of some fun Rankin family history issues. He also caused considerable controversy in his denomination during his lifetime. Genealogical questions aside, Rev. Adam’s life is a story unto itself.

Here are the major issues about Rev. Adam:

-

- What was Rev. Adam’s life all about? He is famous for stoking the flames of an uproar about an arcane theological issue. He was rabidly fanatic on the matter, and that may be an understatement.

- Who were Rev. Adam’s parents? I have found no evidence of Rev. Adam’s family of origin in traditional primary sources such as county records – deeds, wills, tax lists, marriage records, and the like. Instead, there is only secondary evidence, usually deemed less reliable than primary evidence. In Rev. Adam’s case, however, the secondary sources are unusually credible.

- What is the Y-DNA evidence about Rev. Adam’s line? Y-DNA testing establishes that Rev. Adam was a genetic relative of Adam and Mary Steele Alexander Rankin, as family tradition claims.

Rev. Adam’s theological mess

There is a wealth of evidence regarding Rev. Adam’s personality in history books. George W. Rankin’s 1872 History of Lexington describes Rev. Adam as a “talented, intolerant, eccentric, and pious man, [who] was greatly beloved by his congregation, which clung to him with devoted attachment through all his fortunes.”[1]

Even more colorfully, Rev. Robert Davidson’s 1847 history of Kentucky Presbyterianism says that Rev. Adam “appears to have been of a contentious, self-willed turn from his youth … and his wranglings at last ended in a schism. Obstinate and opinionated, his nature was a stranger to concession, and peace was to be bought only by coming over to his positions … his pugnacious propensities brought on at last a judicial investigation.”[2]

An early twentieth-century Kentucky history describes Rev. Adam as “a strange, eccentric man, a dreamer of dreams, a Kentucky Luther, and, perhaps, a bit crazed with the bitter opposition his views received.”[3]

What on earth do you suppose all the fuss was about?

Ahem. The theological issue about which Rev. Adam was fanatical is the so-called “Psalmody controversy.” Psalmody, said Rev. Davidson, was “his monomania.”

The what controversy? I have a friend who is a retired Presbyterian minister, and he has never heard of it.

An article titled “How Adam Rankin tried to stop Presbyterians from singing ‘Joy to the World’” describes the issue and its origins:

“In 1770 [sic, 1670], when Isaac Watts was 18 years of age, he criticized the hymns of the church in his English hometown of Southampton. In response to his son’s complaints, Watts’ father is reputed to have said, ‘If you don’t like the hymns we sing, then write a better one!’ To that Isaac replied, ‘I have.’ One of his hymns was shared with the church they attended and they asked the young man to write more.

For 222 Sundays, Isaac Watts prepared a new hymn for each Sunday, and single-handedly revolutionized the congregational singing habits of the English Churches of the time. In 1705, Watts published his first volume of original hymns and sacred poems. More followed. In 1719, he published his monumental work, ‘The Psalms of David, Imitated.’ Among those many familiar hymns is the Christmas favorite ‘Joy to the World,’ based on Psalm 98.

For many years, only Psalms were sung throughout the Presbyterian Churches and the old ‘Rouse’ versions were the standard. The first General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States convened at the Second Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia in 1789. One of the Prebyterian ministers of the time, a man by the name of Rev. Adam Rankin, rode horseback from his Kentucky parish to Philadelphia to plead with his fellow Presbyterians to reject the use of Watts’ hymms.”[4]

Rev. Adam had to be a virtual lunatic on the issue to ride more than 600 miles from Lexington to Philadelphia, right? Assuming the Reverend’s horse was capable of 12-hour days at an average speed of four miles per hour, that’s a good 12-day trip each way.[5] And we must surely assume that Rev. Adam rested on the Sabbath.

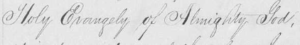

The trip is even more extraordinary because Rev. Adam had no “commission” to attend the Assembly, meaning he was not an official attendee.[6] He simply requested to be heard by the Assembly on the subject of Psalmody. Specifically, he sought a repeal of a 1787 resolution allowing Watts’ hymns to be used in churches. Rev. Adam presented this query to the General Assembly:

“Whether the churches under the care of the General Assembly, have not, by the countenance and allowance of the late Synod of New York and Philadelphia, fallen into a great and pernicious error in the public worship of God, by disusing Rouse’s versification of David’s Psalms, and adopting in the room of it, Watts’ imitation?”[7]

The Assembly listened to him patiently. Then it urged (gently, it seems to me) Rev. Adam to behave in a similar fashion by extending “that exercise of Christian charity, towards those who differ from him in their views of this matter, which is exercised toward himself: and that he be carefully guarded against disturbing the peace of the church on this head.”[8]

You can probably guess how well Rev. Adam followed that advice:

“No sooner had he returned home than he began to denounce the Presbyterian clergy as Deists, blasphemers, and rejecters of revelation, and debarred from the Lord’s Table all admirers of Watts’ Psalms, which he castigated as rivals of the Word of God.”[9]

Emphasis added. “Debarred from the Lord’s Table” means that Rev. Adam refused to administer communion to parishioners who disagreed with him about Watts’ hymns. It is hard to imagine a more radical punishment in a Presbyterian church short of, I don’t know, burning dissenters at the stake.[10]

Rev. Adam didn’t mince words. He verbally abused his Psalmody opponents in ways that would make even some partisan politicians cringe. He called them weak, ignorant, envious, and profane, compared them to swine, said they bore the mark of the beast and that they were sacrilegious robbers, hypocrites, and blasphemers. It makes Newt Gingritch’s instruction to his House colleagues circa 1986 to call members of the opposing party “traitors” and the “enemy” seem almost collegial by comparison.

In 1789, several formal charges were brought against Rev. Rankin before the Presbytery to which his church belonged. One charge was that he had refused communion to persons who approved Watts’ psalmody. Apparently attempting to dodge a trial, he made a two-year trip to London. When he returned, his views unchanged, his case was tried in April 1792. Rev. Adam just withdrew from the Presbytery, taking with him a majority of his congregation.[11]

He then affiliated with the Associate Reformed Church, although the honeymoon was brief. Rev. Davidson wrote that Rev. Adam “was on no better terms with the Associate Reformed than he had been with the Presbyterians; and his pugnacious propensities brought on at last a judicial investigation.” In 1818, he was suspended from the ministry. He and his congregation simply declared themselves independent.

Rev. Adam wasn’t merely stubborn and pugnacious. He may also have been somewhat deluded. He claimed early on that he was guided by dreams and visions, convinced that “God had raised him up as a special instrument to reinstate ‘the Lord’s song.’” Eventually, he was led by a dream to believe that “Jerusalem was about to be rebuilt and that he must hurry there in order to assist in the rebuilding. He bade his Lexington flock farewell, and started to the Holy City, but, on November 25, 1827, death overtook him at Philadelphia.”[12]

I find myself wishing he had made it to Jerusalem just to see what happened. Of course, there is no telling what additional trouble we might now have in the Middle East if he had done so.

Rev. Adam’s widow moved to Maury County, Tennessee along with her sons Samuel and Adam Rankin Jr. She died there. Her tombstone in the Greenwood Cemetery in Columbia reads simply “Martha Rankin, consort of A. Rankin of Lexington, KY.”[13] It was probably no picnic, being a planet in Rev. Adam’s solar system.

Moving on to the next issue …

Who were Rev. Adam’s parents?

As noted, there appears to be no primary evidence available on Rev. Adam’s family of origin. The family oral tradition is that he was a son of Jeremiah and Rhoda Craig Rankin of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. Jeremiah, in turn, was one of the three proved sons of the Adam Rankin who died in 1747 in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania and his wife Mary Steele Alexander Rankin.

Family tradition also says that Jeremiah died young in a mill accident. There are no probate records in the Rankin name concerning his estate in Cumberland County, so far as I have found. There should be, because he owned land inherited from his father. Likewise, I haven’t found any guardian’s records in Cumberland, although Jeremiah’s children were underage when he died. In fact, the only reference I have found to Adam’s son Jeremiah in county records is Adam’s 1747 Lancaster County will.[14] I may have missed something. It wouldn’t be the first time. Or perhaps the records no longer exist.

Fortunately, there are at least two pieces of credible secondary evidence about this family: (1) Rev. Robert Davidson’s History of the Presbyterian Church in the State of Kentucky and (2) oral tradition preserved in an 1854 letter written by one of Rev. Adam’s sons. Both provide evidence concerning Rev. Adam’s family of origin.

Here is what Rev. Davidson wrote about Rev. Adam (boldface and italics added).

“The Rev. Adam Rankin was born March 24, 1755, near Greencastle, Western Pennsylvania [sic, Greencastle is in south-central Pennsylvania]. He was descended from pious Presbyterian ancestors, who had emigrated from Scotland, making a short sojourn in Ireland by the way. His mother, who was a godly woman, was a Craig, and one of her ancestors suffered martyrdom, in Scotland, for the truth. That ancestor, of the name of Alexander, and a number of others, were thrown into prison, where they were slaughtered, without trial, by a mob of ferocious assassins, till the blood ran ancle [sic] deep. This account Mr. Rankin received from his mother’s lips. His father was an uncommon instance of early piety, and because the minister scrupled to admit one so young, being only in the tenth year of his age, he was examined before a presbytery. From the moment of his son Adam’s birth, he dedicated him to the ministry. He was killed in his own mill, when Adam, his eldest son, was in his fifth year. [Rev. Adam] graduated at Liberty Hall [now Washington & Lee University], about 1780. Two years after, Oct. 25, 1782, at the age of twenty-seven, he was licensed by Hanover Presbytery, and, about the same time, married Martha, daughter of Alexander McPheeters, of Augusta county.”[15]

Perhaps the most important thing Rev. Davidson said about Rev. Adam was in a footnote: “This sketch of Mr. Rankin’s early history so far is derived from his autobiography, prepared, shortly before his decease, for his friend, Gen. Robert B. McAfee, then Lieut. Governor of the State.” That qualifies as information straight from the horse’s mouth, so to speak.[16] Several facts stand out in Rev. Davidson’s sketch:

-

- The death of Rev. Adam’s father in a mill accident confirms the family oral tradition. The date is established at about 1760-61, when Rev. Adam was in his fifth year.[17]

- Adam’s mother was, as the family history says, a Craig.[18]

- There was a Presbyterian martyr among Rev. Adam’s ancestors, although the murdered man was his mother’s ancestor, not his father’s. The oral family history in this branch of the Rankin family identifies the pious Scots ancestor as Alexander Rankin, two of whose sons were reportedly martyred before the survivors escaped to Ulster. The failure of Rev. Adam’s autobiography to reference that legend suggests he probably never heard it.

- Adam was born in Greencastle, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. That county was created in 1750 from Lancaster, where Adam and Mary Steele Alexander Rankin lived. Adam and Mary’s sons William and James began appearing in Cumberland in the 1750s. Rev. Adam’s birth in Greencastle is consequently good circumstantial evidence that he was from the family of Adam and Mary Steele Rankin.

The other significant piece of evidence regarding Rev. Adam’s family is an 1854 letter written by John Mason Rankin, Rev. Adam’s youngest son.[19] It has copious genealogical information about John Mason’s siblings, nieces and nephews, and extended family. John Mason obviously wrote from personal knowledge as to his father’s generation and their children, all of whom lived in Fayette and Woodford Counties, Kentucky. He also had information from the family’s oral tradition regarding the family’s earlier ancestry. Most importantly, his mother also lived with him near the end of her life. I would bet that she was an impeccable source of information about her family.

The original of John Mason Rankin’s letter is supposedly in the custody of a museum in San Augustine, Texas. Gary and I visited there in 2024, and the museum custodian had never heard of such a letter and didn’t know where it might be located. Fortunately, there is a lovely little library in San Augustine which features a genealogical section and an extremely helpful librarian. She had a Rankin file including xerox copies of the 1854 letter, as well as a less significant letter written earlier.

There are a couple of interesting things about the 1854 letter, in addition to the wealth of genealogical detail. First, it has some important information that is contradicted by John Mason Rankin’s Bible. Second, there are some minor and unsurprising errors.

First, John Mason identified the original immigrants in his Rankin family as the brothers Adam (his ancestor), John, and Hugh. This precisely echoes information contained on the famous bronze table in the Mt. Horeb Presbyterian Cemetery in Jefferson County, Tennessee. The tablet has a colorful story about the Rankin family in Scotland and Ireland that is worth reading.[20]

The Mt. Horeb tablet also identifies the family’s original Rankin immigrants as the brothers Adam, John and Hugh, and names Adam’s wife Mary Steele. That makes it certain that John Mason Rankin and the Mt. Horeb tablet were dealing with the same immigrant family. John Mason says he descends from Adam and Mary Steele Rankin. The Mt. Horeb Rankins descend from the John Rankin who died in 1749 in Lancaster. John was reportedly Adam’s brother according to both family traditions. Y-DNA testing has disproved that theory: Adam and John were NOT genetic kin.

The John Mason and Mt. Horeb tablet legends diverge prior to the Rankin immigrant brothers, however. John Mason’s letter does not include the colorful stories of Alexander Rankin and his sons in Scotland and Ireland. That part of the Mt. Horeb legend was apparently also omitted from Rev. Adam’s autobiography, or Rev. Davidson would surely have mentioned it. This creates an inference that the Mt. Horeb legend about the Killing Times in Scotland and the Siege of Londonderry in Ireland may not have been a part of Rev. Adam’s family’s oral history. That is my own belief.

In the interest of full disclosure, here are some minor errors or discrepancies in John Mason’s 1854 letter:

-

- Adam Rankin (wife Mary Steele Alexander) died in 1747, not 1750.

- John Mason identified the father of the three immigrant Rankins (John, Adam, and Hugh, allegedly brothers) as Adam. The Mt. Horeb tablet identifies the three men’s father as William. John Mason Rankin’s Bible also identifies the three men’s father as William. So far as I know, there is no evidence regarding the identity of either Adam’s or John’s father. The owner of the Bible, however, believes the information in the Bible is correct — the immigrant Adam’s father was named William — and that John Mason Rankin simply erred in the 1854 letter. For a variety of reasons, I agree.

- What John Mason called “Cannegogy Creek” usually appears in the colonial records as “Conogogheague” Creek. In later records, it is spelled “Conococheague.” In any event, John Mason was clearly talking about the creek where Jeremiah’s mill was located. Two Presbyterian churches on or near that creek are the churches attended by Adam and Mary Steele Rankin’s sons William and James. That puts the three proved sons of Adam – James, William, and Jeremiah – in close geographic proximity, a nice piece of circumstantial evidence supporting their family relationship.

- Jeremiah Rankin, Rev. Adam’s brother, had four sons, not three: Adam, Joseph, Andrew, and Samuel.

And that brings us to the last issue …

Y-DNA evidence concerning Rev. Adam’s line

A male descendant of Rev. Adam Rankin – a son of Adam and Mary Steele Rankin’s son Jeremiah – has Y-DNA tested and is a participant in the Rankin project. He is a 67-marker match with a genetic distance of 5 to a man who is descended from Adam and Mary Steele Rankin’s son William. That isn’t a particularly close Y-DNA match. Their paper trails nonetheless indicate with a high degree of confidence that Adam of Lancaster County is their common Rankin ancestor. Their Big Y results confirm it.

Six proved descendants of the John Rankin who died in 1749 in Lancaster have also Y-DNA tested and participate in the Rankin DNA project. They are a close genetic match to each other, and their paper trails are solid.

Here’s the rub. The six descendants of John are not a genetic match with the two descendants of Adam. Unless some other explanation can be found, the mismatch means that John and Adam did not have the same father. Let’s hope that more research and/or Y-DNA testing will shed further light on the issue.

One more thing: I posted an article about the John Mason Rankin letters after our trip to San Augustine. See it here.

And that’s all the news that’s fit to print. See you on down the road.

Robin

* * * * * * *

[1] George W. Rankin, History of Lexington, Kentucky (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1872) 108-110.

[2] Rev. Robert Davidson, History of the Presbyterian Church in the State of Kentucky (New York: R. Carter, 1847) 95. For “The Rankin Schism,” see p. 88 et seq. The book is available online here.

[3] John Wilson Townsend and Dorothy Edwards Townsend, Kentucky in American Letters (Cedar Rapids, IA: The Torch Press, 1913) 17.

[4] Staff of the Ebenezer Presbyterian Church, March 20, 2015, “How Adam Rankin Tried to Stop Presbyterians From Singing ‘Joy to the World,’ published by The Aquila Report at this url.

[5] Average horse speed stats are available at this website. Estimated distance is from Google maps. I would bet the one-way trip took more than 12 days.

[6] Davidson, History of the Presbytrian Church 82.

[7] Ernest Trice Thompson, Presbyterians in the South, Volume One: 1607-1861 (Richmond: John Knox Press, 1963) 115-116.

[8] Id. at 218-219.

[9] Id.

[10] I was baptized and confirmed in, and currently belong to, a Presbyterian church. I am, after all, a Scots-Irish Rankin. My church’s motto is “ALL ARE WELCOME.” That phrase has several layers of meaning in this era of immigrant hatred, but its most fundamental meaning is that everyone is invited to participate in communion.

[11] Rankin, History of Lexington, Kentucky 108-110.

[12] Townsend, Kentucky in American Letters 17.

[13] Fred Lee Hawkins Jr., Maury County, Tennessee Cemeteries with Genealogical and Historical Notes, Vols. 1 and 2 (1989).

[14] Lancaster Co., PA Will Book J: 208, will of Adam Rankin dated 4 May 1747, proved 21 Sep 1747. Adam devised land to his sons James, Adam, and Jeremiah.

[15] Davidson, History of the Presbyterian Church in the State of Kentucky 95. Chapter III of the book is titled “The Rankin Schism,” 88 et seq. The book is available online as a pdf, accessed 30 Aug 2018.

[16] I’m looking for that autobiography. No luck so far.

[17] I said Rev. Adam’s father died “about” 1760-61 simply because of the difficulty a 70-year-old man would naturally have pinpointing the exact time something happened when he was a child. Also, Rev. Davidson said that Rev. Adam “was in his fifth year.” I’m not sure whether tthat means he was four going on five, or five going on six.

[18] Rev. Davidson may have been more impressed by the Craig connection than the Rankin name on account of Rev. John Craig, a famous Presbyterian minister from Ireland who lived in Augusta Co., VA. See, e.g., Katharine L. Brown, “John Craig (1709–1774),” Dictionary of Virginia Biography, Library of Virginia, published 2006 available online here.

[19] You can find a transcription of the 1854 letter at this link.

[20] See a transcription of the Mt. Horeb tablet in Chapter 4 here.