Every genealogist knows that names can be reliable pointers to ancestral lines. And that pursuing your family tree inevitably produces some good stories. I’m sharing some of both here.

Burke

Our first son’s name is William Burke Willis. William is downright generic, but Burke is a solid clue. In fact, my mother’s birth surname was Burke. Her father was William Logan Burke (“WLB”). Thus, our son was obviously named for my grandfather, known as W. L. or “Billy” Burke. That name persisted: Gramps was one of at least five William Logan Burkes in the family.

The first WLB was born in 1860 in Wilson County, Tennessee. He migrated to Waco, Texas, where he became an early Sheriff and U. S. Marshall of McLennan County. The Sheriff’s father was Esom Logan Burke — thus the “L” in those five middle names. I haven’t proved a Logan on the Burke tree, but I’ll wager there is one.

Here are two Burke stories.

My earliest proved Burke ancestor was John Burke of Jackson County, Tennessee. John owned a fair amount of land on White’s Bend of the Cumberland River. Beautiful county, that is. He had a ferry there, owned enslaved persons, and ultimately fathered sixteen children in two marriages. Some of the sons turned out to be what my grandmother would call “no account,” but Esom Logan was a solid citizen, a Wilson County farmer.

John was born in Virginia during 1780-1790. He has accounted for a fair share of my gray hair: I cannot prove his parents. An early family history undoubtedly contains a great deal of truth, but is likely wrong about John’s parents. Y-DNA has not yet helped.

Desperate, I consulted the Draper Manuscripts. This is a vast trove of historical records, including letters, genealogical and historical notes, land records, newspaper clippings, and interview notes, all collected by Lyman Copeland Draper, a Wisconsin historian. The collection focuses on the frontier history and settlement of the old Northwest and Southwest Territories of the US from the 1740s to 1830. Draper’s papers are assembled in 491 volumes. To describe the collection as labyrinthine would be a massive understatement.

When you are looking for info in Tennessee around 1800 or so and are in a masochistic mood, head for the microfilms of the Draper Manuscripts. First, though, consult a book titled Guide to the Draper Manuscripts or something along those lines.

Lo and behold, I found a John Burke in a Tennessee volume! Draper described him as a renowned teller of fabulous tall tales. The example recounted by Draper: a near neighbor, let’s call him Thomas, was riding home one day and saw John out in the field. Thomas called out to him.

John, said Thomas, how about if you tell me one of your famous tall tales?

John didn’t miss a beat. You don’t have time for such foolishness, he said. I just saw one of your cows loose in your cabbage patch having a fine meal.

The neighbor headed home at a brisk trot. There was no cow in the cabbage patch, of course.

I am not certain that the above John Burke was the same man as my ancestor John Burke of Jackson County. I have not been able to find that story again, hoping it might identify the county where John the storyteller lived. That probably says something about the accessibility of the Draper Manuscripts. However, I definitely know that my grandfather, the second WLB, was also a fabulous storyteller. My grandmother tore out a clipping from one of the Houston newspapers one day and mailed it to my mother, writing on it, “your daddy in print with a big one.” Here is a transcription of the clipping, a column by Bill Walker titled “The Outdoor Sportsman.”

“A roaring gas flame in the big brick fireplace in the Cinco Ranch clubhouse warmed the spacious room and the several members of the Gulf Coast Field Trial Club who gathered there for coffee Saturday morning before the first cast in the shooting dog stake.

“Usually when veteran field trial followers get together the conversation turns to great dogs of yesteryears and this group was no exception.

“W. L. “BILLY” BURKE related one about an all-time favorite of ours — Navasota Shoals Jake.

“Burke and the late W. V. Bowles, owner of Ten Brock’s Bennett and Navasota Shoals Jake, were hunting quail in the Valley on one of those rare hot and sultry winter mornings. Jake pointed a covey several hundred yards from the two men and out in the open.

“BOWLES suggested they take their time approaching the pointing dog, since he was known to be very trustworthy. When the two hunters did not immediately move to Jake, the dog broke his point, backed away to the cool shade of a nearby tree and again pointed the birds.

“THE COVEY was still hovering in a briar thicket when Bowles and Burke arrived. Navasota Shoals Jake was still on point.”

Lindsey

OK, moving on. Our second son is named Ryan Lindsey Willis. Yep, there are Lindseys on my tree — one of my favorite lines. My nearest Lindsey ancestor’s name was Amanda Adieanna Lindsey Rankin. I loved her as soon as I learned the name; I wish I had her picture. She answered a knock on the front door of her father’s Monticello, Arkansas house one night in 1863, and immediately fell in love (according to her recounting) with “the handsomest soldier you ever saw.”

That was John Allen Rankin, wearing an almost brand-new uniform. The last battle in which he had fought was Champion’s Hill, east of Vicksburg, where the Confederates were soundly beaten. They were out-generaled. The Confederate in charge, General Stephen Lee (no relation to Robert E.), marched his soldiers piecemeal into Grant’s entrenched position.[1] About 4,300 Confederate soldiers and 2,500 Union soldiers were casualties. It was considered a Union victory and a decisive battle in the Vicksburg campaign.

On 19 May 1863, whatever was left of John Allen’s division after Champion’s Hill arrived at Jackson, Mississippi. He was in the 1st Mississippi CSA Hospital in Jackson from May 31 to June 13, 1863. The diagnosis: “diarrhea, acute.” That was near the end of the second year of his one-year enlistment.

On September 1, 1863, now in Selma, Alabama, the army issued John Allen a new pair of pants, a jacket and a shirt, all valued on the voucher at $31.00. Good wool and cotton stuff, presumably. Probably the best suit of clothes John Allen ever owned. That was the last the Rebel army ever saw of him. He was shortly declared AWOL and placed under arrest in absentia.

The next thing you know, he was in Monticello, making Amanda Lindsey swoon.

My earliest conclusively proved Lindsey ancestor was a William who died in 1817 in Nash County, North Carolina.[2]He left a charming will instructing his eldest son John Wesley Lindsey to “see that thay [the younger children] mind thare Stepmother and thare larning bisness and are kept out of all dissepated cumpaney and also to have sum chance of schoolling at least to know how to read the word of God.”[3]

William’s youngest son, Edward Buxton Lindsey — my ancestor — is also a story. When he was sixteen, he attended an auction of a deceased brother’s estate. Undoubtedly under the watchful eye of his brother John Wesley, Edward acquired almost everything he needed to start adult life and continue his larning bisness: a bedstead and linens, a pocket knife, a man’s saddle, a razor, an arithmetic book, a cyphering book, and an ink stand.

Edward married four times, which was a serious disgrace in the eyes of his daughter Amanda. He wound up old and widowed in Claiborne Parish, Louisiana in 1880, raising a young son from his last marriage. I felt sorry for him and tried fruitlessly to find his grave, hoping to pay my respect. I don’t think he got much of that from anyone else, except for two of those four wives: two wives divorced him and two died, including Elizabeth Odom Lindsey, his first wife and Amanda’s mother. I wish I had a picture of him, too. He must have been a charmer.

Estes

Family names are usually a blessing (see Burke, above). Sometimes they create chaos. Case in point: my ancestor Lyddal Bacon Estes (“LBE”). My irreverent husband calls him Little Sizzler.

When I identified LBE as the father of Mary F. Estes who married Samuel Rankin (parents of John Allen, the Confederate deserter), I rubbed my hands in glee. With those three surnames, I reasoned, finding his parents would be a piece of cake. Hahahaha …

The genealogy gods apparently do not like cockiness.

Turned out there were three men named Lyddal Bacon Estes whose lifetimes overlapped (not counting my LBE’s namesake son). One of them probably did not have the middle name Bacon, or at least he left no record of either a name or middle initial, notwithstanding appearances in county records.

All three LBEs trace are from the same Estes line of Virginia. And those three surnames don’t lie: there are both Bacon and Lyddall ancestors on my tree. As it turned out, I had to sift through hundreds of Estes records in Lunenburg County, Virginia, searching for LBE’s parents. Conclusive proof nevertheless eluded me. I finally proved them to my satisfaction by the process of elimination: there was only one male Estes in the huge Lunenburg Estes family who could reasonably have been LBE’s father. And only one female, also an Estes, who could reasonably have been his mother.[4]

I like the Estes line, too. The original immigrant to the Colonies was an Abraham Estes, a fine given name for the first of the line to arrive here. The Estes family traces back nicely to Kent, England in the late 1400s. They lived on the east coast and were fisherman and linen weavers.

Broadnax

Also in Kent were my Broadnax family ancestors, a set of certifiable bluebloods. The original immigrant to the Colonies was John Broadnax, a Cavalier, who was undoubtedly fleeing from Cromwell’s. He left his family behind in England. He appeared in Virginia just long enough to have his inventory recorded in York County.

I don’t much care for the Broadnax line because (1) it has been so thoroughly researched it is not challenging (and is therefore no fun) and (2) my view of my father’s mother, Emma Leona Broadnax “Ma” Rankin is my most recent Broadnax ancestor. Ma was, uh, how shall I say this? Not exactly warm and fuzzy. She was an unsmiling, bigoted, tea-totaling Southern Baptist who kept her house in Gibsland, Bienville Parish, Louisiana, heated to about 90 degrees. No mechanical assistance was necessary to achieve that temperature in the summer, it being Louisiana and all. But the heating bills in winter must have been spectacular, especially considering the high ceilings in that old house.

Ma’s husband, John Marvin “Daddy Jack” Rankin, son of the Rebel deserter, was poor as a church mouse. I once asked my favorite Rankin cousin — Butch, we called him as a kid, so he is stuck with that moniker for life — what Daddy Jack did for a living. All of my Rankin cousins were or are considerably older than I, my father being the youngest of the four Rankin siblings and not becoming a father until the ripe old age of 39. So they all know more than I did about the Gibsland Rankins.

Butch’s succinct response: Anything he could, hon. Anything he could. He was a driver of a dray wagon in one census and a waiter in a restaurant in another. A certificate among my father’s records proves he was Bienville Parish sheriff for one term, another non-lucrative profession.

The cousins once showed me an old popcorn wagon stored under the rear of the Rankins’ Gibsland house, which was built on a steep slope. We all figure Daddy Jack sold popcorn from time to time, perhaps turning a profit when Bonnie and Clyde were killed and their corpses displayed in GIbsland. Ma Rankin took in mending to help make ends meet, although they often did not. The Rankin fortunes didn’t revive until their kids, or at least their three sons, escaped rural North Louisiana.

At the first Rankin Cousins reunion at Butch’s house in 1995-ish, my cousin Diane, a child psychiatrist, asked me why in hell Ma Rankin, from the still-wealthy Broadnax family despite a serious setback after the Civil War, married penniless Daddy Jack.

Are you kidding me, Diane? You remember her, uh, personality? She cannot possibly have had many prospects.

One of the cousins, Ellis Leigh Jordan, brought a movie camera to the reunion. He trained it on each of the seven cousins individually and made us tell something about Ma. The word “strict” was grotesquely overused. All four of Ma’s children turned out to be atheists, not surprising in light of Ma’s relentless proselytizing. Furthermore, a fondness for alcohol persisted in the family. Nobody knows where any genetic propensity came from. I think being raised by Ma would drive anyone to drink.

I never knew Daddy Jack, who died in 1932 at age 56. But I knew Ma well enough. Gibsland is sufficiently close to Shreveport, where I grew up, to allow for monthly Sunday visits. I hated those visits with a passion. To describe Ma as merely humorless would prove that either my imagination or my vocabulary is failing me. “Strict” isn’t adequate, either. She once stopped a desultory conversation dead in its tracks, a bullet through its brain, like so …

The setting was her hot-as-hades living room at a Thanksgiving get-together. At least three and perhaps all four of Ma’s children were in attendance. Grandchildren were there as well, restlessly squirming in our seats. At least I was squirming: this was 1957, and I was only eleven. My cousin Marvin, the next youngest, was 15 or 16; Butch and Diane were 18. Ma’s favorite conversational topic was usually other people’s gall bladders, her own still being intact. Thankfully, that topic died quickly for lack of subjects.

Uncle Louie, Diane’s father, finally tried to break one of the prolonged silences by commenting on Sputnik, the satellite launched by the USSR the previous May.

Pretty soon someone will put a man on the moon, Louie opined.

Ma, arms crossed over her chest, fired her conversation-ending bullet: If God had meant for man to be on the moon, he would’ve put him there.

My cousins and I fled to the yard, where we pelted each other with pecans. The frigid cold was a respite.

… And now I have gone on too long. It was fun writing this.

See you on down the road. I’m happy to say that another contribution from Spade is in the works.

Robin

* * * * * * * * * *

[1] General Stephen Lee used exactly the same awful strategy at the Battle of Ezra Church, west of Atlanta, and got Allen W. Estes, brother of Mary Estes Rankin, killed.

[2] Although I cannot conclusively prove his parents, William Lindsey’s grandfather — was a William of Brunswick Co., VA and Edgecombe Co., NC. William had three proved sons: William, Joseph, and John. Y-DNA establishes that one of them was my William’s father, but I can only prove that it wasn’t Joseph. I suspect it was the other William.

[3] North Carolina State Library and Archives, CR069.801.6, “Nash Co. Wills 1778 – 1922, Keith – Owen,” file folder for William Lindsey dated 1817, containing a handwritten will of William Lindsey dated 16 Feb 1817 and proved May 1817.

[4] LBE’s parents were first cousins: John Estes, son of Elisha Estes and Mary Henderson, and Mary Estes, daughter of Benjamin Estes and Frances Bacon. Elisha and Benjamin were sons of the Lunenburg Estes patriarch, Robert Estes Sr. Robert Sr. was a son of Abraham the immigrant. In yet another illustration of the value of names, LBE’s first son was named Benjamin Henderson Estes. His first daughter, my ancestress, was Mary Frances.

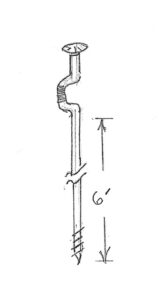

Her idea was to “drill down into some of the coffins to extract DNA.” Thus her nickname. She died not long thereafter, apparently not having succeeded with her DNA recovery project. If she had, any human DNA would undoubtedly have been mixed with pine tree DNA. Not sure if FTDNA could handle that.

Her idea was to “drill down into some of the coffins to extract DNA.” Thus her nickname. She died not long thereafter, apparently not having succeeded with her DNA recovery project. If she had, any human DNA would undoubtedly have been mixed with pine tree DNA. Not sure if FTDNA could handle that.