Several years ago, a researcher asked if Andrew Willis, a Revolutionary War pensioner who died in 1823 in Washington County, Maryland, was descended from the immigrant John Willis of “Wantage” in Dorchester County. I published an article concluding we could not make that connection. Now, thanks to Sherry Taylor’s investigation of her Willis lines, it turns out we were wrong! Revolutionary War muster rolls, pension files, census records, deeds, and probate filings establish that Washington County Andrew was a brother of Jarvis Willis, another Revolutionary War veteran and a proved descendant of Wantage John. Also, a tip of the hat to David McIntire, a researcher who almost nailed this years ago. Below is the revised article; the original has been sent to the trash.

The Question

Washington County Andrew was a Revolutionary War veteran who received a pension for service as a private in the 5th Regiment of the Maryland Line. There are five men named Andrew who were descended from Wantage John Willis and alive during the relevant period. Was one of those five the same man as the pensioner in Washington County? This article describes Washington County Andrew’s nuclear family and his geographic location. It then looks at each of the five men to see if they fit the facts about Washington County Andrew — his family makeup, geographic location, and military service. A bust on any of the three parameters means that particular person was not the same man as Washington County Andrew.

Washington County Andrew – The Facts

Andrew Willis first appears in Washington County, Maryland in the 1800 census. That census lists him with (presumably) a wife, three sons, and two daughters.[1] The 1810 census shows him with the same family members.[2]

In 1812, Edward Willis (who is proved as Andrew’s son) purchased a small tract of land in Washington County on Antietam Creek.[3] His father was about 60 years old at that time. Edward may have purchased land his father had been renting and effectively became the head of household.

In 1818, Andrew applied for a pension. He stated he had served in the Maryland Fifth Regiment, had resided in Washington County for about twenty years, was 66 years old (thus born about 1752), was a laborer but unable to work, owned no home of his own, was impoverished, and his wife was old and frail. He said they lived with a son whom he did not identify.[4] He was awarded a pension paid from 31 Mar 1818 through his death on 4 Dec 1823. His pension was then paid to his wife Lettie/Letha Willis until her death.

As expected from the pension application, the 1820 census did not list Andrew Willis. It named Edward Willis heading a household that apparently included his parents, his brother and wife, and his sister. Subsequent records provide their names: brother and sister-in-law Isaac and Nancy, and sister Elizabeth.[5]

Edward died intestate in 1825 with a very small estate and no widow or children.[6] Under Maryland law, his estate went to his surviving parent(s) or to his siblings and their heirs if his parents were deceased. In 1829, Edward’s heirs sold the Antietam Creek land. The sellers were Hezekiah Donaldson and his wife Sarah, Nehemiah Hurley and his wife Elizabeth, and Isaac Willis and his wife Nancy.[7]

Edward’s mother did not participate in the sale, so she had already died. Sarah Donaldson, Elizabeth Hurley, and Isaac Willis were Edward’s living sisters and brother. Anyone not included in the deed could not have been a surviving sibling or child of a deceased sibling. That eliminates as possible siblings two Willis males who lived concurrently in Washington County.[8] Also, an unnamed son of Andrew and Lettie who appears in the 1800 and 1810 censuses but is absent from the 1820 census must have died without heirs. Otherwise, he, his spouse, or their child would have participated in the 1829 sale.

The facts prove Washington County Andrew’s nuclear family, as follows:

Andrew Willis b 1752 d 1823

His wife:

Lettie LNU Willis b 1756-65 d before 1829

Their children:

Edward Willis b 1785-90 d 1825

Isaac Willis b 1791-94 d after 1850

Sarah Willis b 1791-94 m in 1818 to Hezekiah Donaldson[9]

Son FNU Willis b 1791-99 d before 1820 Census

Elizabeth Willis b 1800 m between 1820-25 to Nehemiah Hurley

Their daughter-in-law:

Nancy LNU b abt. 1790 m before 1820 to Isaac Willis

The evidence also proves Andrew resided in Washington County from at least 1800 until his death in 1823. The only evidence of his residence prior to that is his army service. The Fifth Maryland Regiment recruited from the counties of Queen Anne’s, Kent, Caroline, and Dorchester on the Eastern Shore. He was almost certainly from one of those counties.

By 1830, the family disappeared from Washington County. After Andrew, Lettie, and Edward died, the surviving family members moved to Ohio. In 1850, son Isaac Willis applied for a grant of land in Ohio based on Andrew’s service in the war. Isaac filed on behalf of himself and the other heirs of Andrew Willis.[10]

Finding the Right Andrew Willis

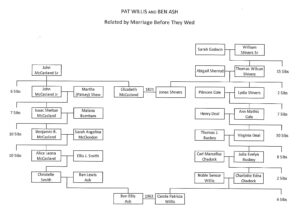

Five descendants of Wantage John Willis who were alive during and after the war are candidates to be the same man as Washington County Andrew. Two were from Caroline County and three from Dorchester. They are shown below in bold face type in an abbreviated descendants’ chart showing their relationship to Wantage John. We will hunt for the man whose family matches the one above and who was in the right place to match Washington County Andrew’s residency and military service.

1) John “Wantage John” Willis d 1712

Caroline County Descendants:

2) John “Marshy Creek John” Willis d 1764

3) John “The Elder” Willis

4) Andrew “Friendship Andrew” Willis d about 1778

5) Andrew No.1 Willis

3) Isaac Willis

4) Andrew No. 2 Willis

Dorchester County Descendants:

2) Andrew “New Town” Willis d. 1738

3) Andrew No. 3 Willis

4) Andrew No. 4 Willis

3) John “New Town” Willis

4) Andrew No. 5 Willis

4) Jarvis Willis

Spoiler Alert!

Andrew Nos. 1 – 3 each had a nuclear family that did not match Washington County Andrew’s. Andrew No. 4 was too young to have served in the war. We can eliminate each (detail shown at the end of the article) and turn to Andrew No. 5, who must have been the same man as Washington County Andrew.

Andrew No. 5

Andrew No. 5 was the possible son of a John Willis in Dorchester County. John who inherited part of a tract called New Town as a contingent devisee when his brother George died. John did not pass New Town to any of his children; he sold it in 1784.[11] That might indicate none of his heirs were interested in the land, or they had moved away.

We know that one proved son , Jarvis Willis, did so. Jarvis served in the army during the revolution and moved to North Carolina after the war.[12] He joined the regular army on 17 Feb 1777, served three years as a Corporal, and was discharged 14 Feb 1780 at Morristown, New Jersey.[13] He then appeared in Stokes County, North Carolina before 1790. Significantly, an Andrew Willis in Dorchester County enlisted in the same regiment and the same company on the same day as Jarvis and was discharged with him at the same place on the same day.[14] Surely, these men were brothers. Jarvis appeared in the Dorchester County 1783 Tax Assessment with no land and eight people in his household.[15]

Jarvis and Andrew showed up in Stokes County, North Carolina by about 1790. That census listed Jarvis Willis with a family of eight, matching his earlier household. Andrew Willis was not in that census but appeared on a Stokes County tax roll in 1791 with 250 acres of land.[16] Jarvis was listed on the same tax roll in the same district. He and Andrew may have shared the land. The 1792 tax roll showed Andrew’s acreage reduced to 200 acres, and Jarvis held 50. On a later roll, Jarvis had 125 acres, half Andrew’s original amount.

By 1793, Stokes County listed Andrew as “insolvent” and owing £5.10 in taxes.[17] Usually, this meant the party had abandoned their land and left the county. Where did he go? If he is the same man as Washington County Andrew, he took his family and retraced their steps 300 miles up the Great Wagon Road to Washington County, Maryland where he appeared in the census in 1800 and applied for a pension in 1818. Such reverse migrations were not common. I usually question the validity of any claim that someone migrated “backwards.”

In this case, the identical army service of Jarvis and Washington County Andrew outweigh any hesitancy about reverse migration. The date of enrollment is especially important. Officers of each company personally enlisted men to fill their ranks. For an officer to enroll two men on the same date meant the men almost certainly were in the same place when they signed up. There was no person more likely to be in the same location as Jarvis Willis on their enrollment date in February 1777 than a brother. With no other Andrew in the vicinity that seals the deal.[18]

Conclusion

Evidence about family makeup eliminates the first three men from being Washington County Andrew. Inability to have served in the army because of his youth rules out the fourth. We have no evidence of the fifth Andrew’s family on the Eastern Shore to compare to the Washington County family. However, there is strong circumstantial evidence implying Jarvis Willis is the brother of the fifth Andrew. His connections to Jarvis are significant – they enrolled in the same Continental Line company at the same time, served for three years, left the army on the same date, and later appeared together and may have shared land in Stokes County, North Carolina. Then Andrew Willis left at just the right time to arrive in Washington County to appear in the census there and to file a pension application. I conclude that the Andrew in Washington County is the brother of the veteran Jarvis Willis and therefore a descendant of Wantage John Willis.

The Descendant Andrews Eliminated

Andrew No. 1

An Andrew Willis acquired land in Caroline County called Friendship Regulated in 1754. After Andrew’s death, his son Thomas distributed the land to his siblings according to his father’s oral instructions. Son Andrew No. 1 received 87½ acres.[19] The Supply Tax List of 1783 shows him in possession of that land with a household of five males and five females. A year later, Andrew No. 1 and his wife Sarah sold the land and did not appear in Caroline County again.[20] Their family, apparently four sons and four daughters (all born before 1783), are too old to be the Washington County family in which no child was born before 1785. Andrew No. 1 is not the same man as Washington County Andrew.

Andrew No. 2

Andrew No. 2 was the son of Isaac Willis and seems at first a likely candidate to be the same man as Washington County Andrew. After all, Washington County Andrew named one of his sons Isaac. Further, Andrew No. 2 disappeared from Caroline County before the 1800 census. Could he have moved to Washington County?

Sure. But the 1783 Supply Tax Assessment in Caroline County shows this Andrew with a household of one male and three females. That does not fit the Washington County family where the male children were older than the females and where no child was born before 1785. This rules out this man as Washington County Andrew.[21]

Andrew No. 3

Andrew No. 3 acquired about 60 acres in 1781.[22] He had that land in the 1783 Supply Tax Assessment for Dorchester County along with a household of seven people. Like the others we have examined, he had children born before 1783, while Washington County Andrew had none that old. He cannot be Washington County Andrew.

Andrew No. 4

Andrew No. 3 had a son, Andrew No. 4, to whom he devised the 60 acres. Andrew No. 4 was born in 1768.[23] He was the right age to have a young family in Washington County, but he was too young to have been in the war as a private. He was only nine when Washington County Andrew enlisted in the regular army and only fifteen when the war ended. He cannot be Washington County Andrew, either.

Again, thank you Sherry Taylor for your work on the Willis lines. Next, I must write about Jarvis Willis, who was Sherry’s primary interest. She is descended from one of Jarvis’s daughters! But I had to correct this article about Andrew first.

______

[1] 1800 Census Washington County, MD. The listing for Andrew Willis includes a man and woman 26-44 years old with two males under 10, one male age 10-15, and two females under 10. Note that if Andrew was born in 1752 per his pension application, the census understates his age by four years, which is not an unusual discrepancy.

[2] 1810 Census Washington County, MD. Ages of all family members track to the next appropriate age category except for the youngest daughter, who remains less than 10. She may have been an infant in 1800 and was 10 years old in 1810. Or, she may have died before 1810 and the census lists a new daughter.

[3] Washington County, MD Deed Book Y: 439.

[4] See Pension File S35141. Andrew stated he could not remember the exact dates but thought he enrolled in 1778 and was discharged in 1781. He was off by one year on both dates, according to official records.

[5] 1820 Census, Washington County, MD shows Edward Willis’s household with two men age 26-44 and one over 45, one female 15-25, one 26-44, and one over 45. The older man and woman are Andrew Willis and his wife Lettie. The two younger men are their sons Edward and Isaac. The youngest female is their daughter Elizabeth. The woman age 26-44 is Isaac’s wife Nancy LNU.

[6] Washington County, MD Bond Book C: 427 and Administrative Accounts Book 7: 413. Nehemiah Hurley was administrator, Nehemiah Hurley, Hezekiah Donaldson and Isaac Willis were bondsmen.

[7] Washington County, MD Deed Book KK: 610.

[8] William Willis and Levin Willis, who appear in census and deed records of the era, were not Edward’s brothers.

[9] Morrow, Dale W., Marriages of Washington County, Maryland, Volume 1, 1799-1830, (Traces: Hagerstown, MD, 1977), D64.

[10] 31 Dec 1850 letter from Bennington & Cowan, St. Clairsville, Belmont County, Ohio on behalf of Isaac Willis, online at Fold 3 pension file S35141 of Andrew Willis. Isaac knew his father was from the Eastern Shore of Maryland but was not sure of the county. He thought it might have been Kent. However, there is no Kent County Andrew. He also thought Andrew’s company commander was named Bentley. That was close. It was Benson.

[11] Dorchester County, MD Deed Book NH 2:546. John Willis sold to Levin Hughes. No signature of a wife, so she is presumed deceased. Also, at NH 2:88 Mary Willis Meekins, widow of Benjamin, sold in 1782 her half of New Town. Both shares originated with Andrew Willis, died 1738, who devised half each to sons Richard and George. George’s share descended to his brother John upon George’s untimely death. Richard willed his share to his daughter Mary who married Benjamin Meekins.

[12] Palmer, 19. 6 Dec 1758, Jarvey [Jarvis] Willis, parents John and Nancy Willis.

[13] Archives of Maryland, Muster Rolls and Other Records of Service of Maryland Troops in the American Revolution, 1775-1783, (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1900), 254. Corporal Jarvis Willis and Private Andrew Willis listed with identical enrollment and discharge dates. https://archive.org/details/musterrollsother00mary

[14] Roll of Lt Perry Benson’s Company, 5th Maryland Regiment of Foot in the service of the United States commanded by Colonel William Richardson, 8 Sep 1778. Corporal Jarvis Willis and Private Andrew Willis appear on the same roster, both sick in hospital.

[15] Andrew did not appear in the tax list. Neither Jarvis nor Andrew appeared in the 1790 census in Dorchester.

[16] Harvey, Iris Moseley, Stokes County, North Carolina Tax List, 1791, (Raleigh, NC, 1998), 11. There is no record showing how Andrew or Jarvis acquired the land.

[17] Harvey, Iris Moseley, Stokes County, North Carolina Tax List, 1793, (Raleigh, NC, 1998), 43

[18] The only other person close by was Andrew No.4 who was nine years old, too young to have been enlisted as a private.

[19] Caroline County, MD Deed Book GFA: 269, 1778

[20] Caroline County, MD Deed Book GFA: 777, 1784

[21] 1790 Census Caroline County, MD lists Andrew Willis with a household inconsistent with the 1783 Tax List. The household has five males age 16 or older, six males under 16, four females, and one slave. Possibly, this is several families living together. In any event it does not match the Washington County family.

[22] Dorchester County, MD Deed Book 28 Old 356. Andrew Willis purchased 59½ acres from Mary and Benjamin Meekins. The tract was originally owned by Henry Fisher and may have been called Fisher’s Venture in the 1783 Supply Tax Assessment.

[23] Palmer, Katherine H., Old Trinity Church, Dorchester Parish, Church Creek, MD, Birth Register, (Cambridge , MD) 19. 12 Feb 1768, Andrew Willis, parents Andrew and Sarah Willis.

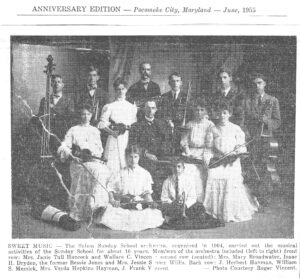

A photo of the group published in the local paper shows her seated at the far right. According to the paper, the ensemble organized in 1904 and played for about ten years.

A photo of the group published in the local paper shows her seated at the far right. According to the paper, the ensemble organized in 1904 and played for about ten years.

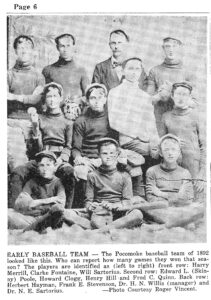

Some team members appear to be high school students, others young adults. This was typical of the era – think “Field of Dreams” – when towns fielded amateur teams for friendly competition.

Some team members appear to be high school students, others young adults. This was typical of the era – think “Field of Dreams” – when towns fielded amateur teams for friendly competition.