Robin Rankin Willis, June 2019

If you are a history buff, the National Museum of American History might be your cup of tea. It is part of the complex of Smithsonian museums on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and it is a real treat to visit.

One of the wonderful exhibits currently on display there is titled “American Stories.” It features an eclectic collection of artifacts from different eras in American history, beginning with the nation’s birth. Items on display include, e.g., a fragment of Plymouth Rock, Abraham Lincoln’s pocket watch, a sample of penicillin mold donated by Alexander Fleming, Willie Mays’s hat, glove and shoes, and the trophy awarded to Gertrude Ederle, the first woman to swim the English Channel. The exhibit has some humor: Sesame Street’s “Swedish Chef” muppet is one of the display items.

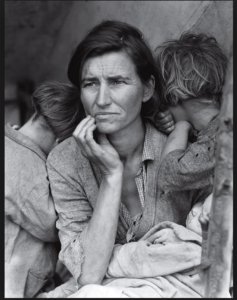

The exhibition also has roughly 200-250 copies of portraits, photos or drawings – perhaps 8”x 8” each? – of Americans displayed on the walls in chronological groupings. The people pictured include politicians, scientists, entertainers, soldiers, social activists, artists, athletes, and a sprinkling of ordinary folks. Some examples: Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Sojourner Truth, Albert Einstein, Babe Ruth, Charles Lindbergh, Thomas Jefferson, Andy Warhol, and an anonymous woman whose photograph became a powerful image of Depression-era Dust Bowl misery.

I was delighted to spot a photograph of a Rankin. A woman, no less: Jeanette Pickering Rankin, the first woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Some of you might recoil at her politics, but still admire her courage and principles. Jeanette’s younger sister Edna was also a remarkable and accomplished person. Here, briefly, are their stories.

Jeanette Pickering Rankin (1880, Montana, – 1973, California)

Rankin was born on a Montana farm in 1880, the eldest of seven children of John and Olive Pickering Rankin. She received a B.S. in Biology in 1902 from the University of Montana, where she was undoubtedly the lone female in her science classes. After graduation, she worked briefly as a schoolteacher, apprentice seamstress, and at a settlement house providing social services to poor immigrants. In 1908-09, she studied social work at the School of Philanthropy (now part of Columbia University) in New York City.

She finally found her calling in 1911, when she became a lobbyist for the National American Suffrage Association. She took a leading role in the women’s suffrage movement in Montana, making speeches and testifying before the legislature. She must have had an impact. In 1914, Montana became one of ten states extending voting rights to women, six years before the 19th amendment was ratified.

In 1916, she was elected to an at-large seat in the U.S. House of Representatives from Montana. She was a Republican. As a freshman representative, she cast one of the two votes for which she is now primarily known. A determined pacifist, she was one of only 50 members of the House of Representatives to vote against entry into World War I. The reaction back in Montana was brutal. One newspaper called her “a dagger in the hands of the German propagandists, a dupe of the Kaiser, a member of the Hun army in the United States, and a crying schoolgirl.”[1]

In 1917, Congresswoman Rankin proposed the formation of a Committee on Woman Suffrage. Naturally, she became chair. In 1918 (after the WWI vote), she addressed the House about the Committee report supporting a constitutional amendment on women’s right to vote. Here is what she said, in part:

“How shall we answer the challenge, gentlemen? How shall we explain … the meaning of democracy if the same Congress that voted to make the world safe for democracy refuses to give this small measure of democracy to the women of our country?”

The resolution supporting the report narrowly passed in the House but died in the Senate.

Here is another picture of her which I imagine to be during that time, although I actually have NO basis for dating the image. She looks younger to me than in the first photograph. Strong woman. Gorgeous, IMO …

Congresswoman Rankin didn’t limit herself to the cause of suffrage. She also introduced the first bill to grant women citizenship independent of their husbands. She introduced the first bill supporting health care for women during pregnancy. According to her 1919 passport application, she took an overseas trip to France, England, Italy, Norway, Holland, Sweden and Switzerland as a newspaper correspondent. I don’t know what subjects her reportage covered, but it is a safe bet that they included feminist issues.

She also supported striking copper miners, an unpopular stance in pro-mining Montana. The state legislature responded by eliminating the at-large voting system for House seats and putting her in a heavily Democratic district. Realizing she had little chance at reelection to the House, she ran for the Senate. She narrowly lost in the Republican primary, despite being vilified in the press.

She spent the 1920s and 1930s working as a lobbyist for various social welfare and antiwar organizations. In the federal census, she described her occupations as “orator” (1920), “lobbyist” (1930) and “secretary, social work” (1940). In 1940, she ran again for a Montana House seat. She won with the support of Fiorello La Guardia and other nationally known progressives. She probably also had the support of Montana women who remembered her work getting them the right to vote.

Then came the House vote for which she is infamous. On December 8, 1941, she was the only member of Congress to vote against a declaration of war with Japan. The verbal hostility directed at her during the roll call vote was so fierce that she was given a police escort back to her office. Of course, a less principled and courageous person might have skipped the vote entirely, knowing it was a hopeless cause.

Discretion being the better part of valor, she did not run for re-election.

She never abandoned either her pacifism or her social activism. In 1968, at the age of 87, she led some 5,000 women who called themselves the “Jeannette Rankin Brigade” on a march to the U.S. capitol building, where they presented an anti-Vietnam War petition to the Speaker of the House. She also wrote letters and gave speeches against the war.

One of the display cases in the “American Stories” exhibition contains a number of political buttons from the sixties and seventies. She would undoubtedly have approved of all of them. They include, for example, buttons saying “Vietnam Moratorium,” “I support the American Agricultural Strike,” “We Shall Overcome,” and “Don’t call me GIRL, I am a WOMAN.” Another button contains the language of the Equal Rights Amendment: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” If a young Jeanette’s voice had been part of the national dialog about that amendment, who knows? The outcome may have been different.

Now, on to her sister …

Edna Rankin McKinnon (1893, Montana – 1978, California)

Jeanette’s sister Edna was the the youngest of the Rankin siblings. Sorry about the blurry photo – it was the best I could find. She went to college at Wellesley, the University of Wisconsin, and the University of Montana, where she received her law degree in 1918. She became the first native-born Montana woman to be admitted to the Montana bar. Like her big sister, she supported equal rights for women, joining a suffrage parade down Pennsylvania Avenue when Woodrow Wilson was reelected in 1918.

In 1919, she married John W. McKinnon. A 1974 article about her published in the Clovis News-Journal said this:

“Edna Rankin McKinnon really had few ambitions: she was a delicately pretty and somewhat frivolous girl who felt that with her marriage to a wealthy young Harvard man she had found her place in life.”

Uh-huh. Edna’s marriage lasted eleven years, then she needed to support herself and her children. Jeanette helped her find a job with the Legal Division of the Resettlement Administration, a New Deal agency created by FDR. Soon after that, she attended a public lecture on birth control, and her vocation was born.

“‘I was electrified,’ she said. ‘My questions tumbled out faster than the speaker could answer them. I had never before heard the subject discussed … And I thought that if my own confusion and ignorance were multiplied millions of times, then the needs of the women of the world were staggering.’ “

She went to work for Margaret Sanger, a pioneer in the field of family planning who went to prison eight times for attempting to open birth control clinics. Yes, some state laws made that a crime: see Griswold v. Connecticut,[2] a 1965 Supreme Court case concerning a Connecticut law that criminalized the encouragement or use of birth control.

Here is some of Ms. McKinnon’s employment history:

- Executive Director of the National Committee for Federal Legislation on Birth Control, a division of the Margaret Sanger Research Bureau

- Field Worker for the Margaret Sanger Research Bureau in Montana, 1937

- Executive Director, Planned Parenthood Association, Chicago

- Field Worker, Pathfinder Fund, which supported family planning in this country and abroad, later supported by a grant from the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Ms. McKinnon visited 32 states helping to establish family planning clinics. Between 1960 and 1966, she traveled to India, Africa, and the Middle East promoting family planning. After officially retiring in 1966, she took another round-the-world tour to continue crusading for family planning.[3]

Edna and Jeanette evidently spent their last years together. Both died in Carmel, Monterrey County, California. Both are buried in the Missoula Cemetery in Missoula County, Montana. You can see Jeanette’s tombstone here and Edna’s tombstone here.

I have not attempted to trace their Rankin ancestry. The 1880 census says their father John was born in Canada and his parents were born in Scotland. There are no surviving Rankins descended from John, as his only son Wellington (yet another accomplished member of this family) died childless. If anyone in this country named Rankin is related to Jeanette and Edna, he or she must descend from an earlier branch of the Rankin family. One of these days, I will try to find a male descendant from that Scots-Canadian Rankin line who might be persuaded to Y-DNA test.

Meanwhile, other Rankins are tugging at my sleeve. See you on down the road.

Robin

Sources:

(1) https://www.history.com/news/7-things-you-may-not-know-about-jeannette-rankin

(2) Max Binheim and Charles A. Elvin, U.S. Women of the West (Los Angeles: Publishers Press, 1928), entry for Rankin, Jeannette.

(3) https://www.biography.com/political-figure/jeannette-rankin

(4) https://mtwomenlawyers.org/1910-1919/edna-rankin-mckinnon-18/

* * * * * * * * * *

[1] I have a hard time visualizing a crying schoolgirl who is a member of an army, but am not surprised that the sophomoric part of that invective was based on her gender.

[2] Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965). The Supreme Court in Griswold declared the Connecticut law an unconstitutional invasion of marital privacy. Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972), established the right of unmarried people to possess contraception on the same basis as married couples.

[3] Edna Rankin McKinnon was the subject of a biography by Wilma Dykeman titled “Too Many People, Too Little Love” (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974).