When I first started writing this blog, another family history researcher told me that people would prefer stories to my academic, footnoted, law-review-style crapola. In all fairness, she didn’t expressly badmouth my articles. She didn’t need to. The statement that people would prefer to read stories instead of, uh, whatever the heck my stuff might be, is about as subtle as the neon lights in Times Square, except less flattering.

In any event, I’m edging toward stories. Gradually. This post is about some relatives and ancestors who left Tennessee for Texas: two Trice brothers, a young male Burke, and a Trice widow with eight children. They all wound up in Waco, McLennan County, Texas. My original plan was to figure out the reason(s) they chose to migrate and craft a story with motivation as the unifying theme. I couldn’t make it work due to lack of both imagination and descriptive skills. All of them apparently went to Texas looking for wide-open spaces and opportunities.

Now, see, that is exactly the sort of thing people say about Texas that makes everyone hate the place. Since I have already lit that fire, however, I’m going to fan the flames by carrying on about Texas for a bit before getting to the Trices and Burkes. Please stick with me, because there are a couple of anecdotes here that might count as stories. A cross-dressing Trice. A Burke with a pet wild turkey. Annoying quail. A bird dog named Navasota Shoals Jake. Also, some cool old photos.

At one time, it seemed like half of Tennessee was heading to Texas. In the period after Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821, more people migrated to Texas from Tennessee than from any other state. Cheap land was undoubtedly the big draw. I doubt anyone was enticed by the fact that every poisonous snake indigenous to North America has a home somewhere in Texas. All four types — rattlers, copperheads, water moccasins, and coral snakes — appear in Harrison County, the location of a summer camp I attended. Frankly, my mother was more difficult to cope with than the snakes, which have a live-and-let-live approach to coexistence. She was also a native Texan. I wonder if that is a non sequitur.

Some of the guys who died at the Alamo in 1836 were among the early wave of Tennessee migrants to Texas.[1] More than thirty Tennesseans fought there, including Davy Crockett.[2] He is the source of what may be the most fabulous sore loser quote in the entire history of American politics. Accepting his loss for a race for a congressional seat from Tennessee, he famously said, “You may all go to hell, and I will go to Texas.” Unfortunately, that didn’t work out well for him. John Wayne did OK.

The state has inspired other noteworthy quotes. Larry McMurtry (author of Lonesome Dove) said “Only a rank degenerate would drive 1,500 miles across Texas without eating a chicken fried steak.”[3] Someone else said that, back in the covered wagon days, you could leave Beaumont with a newborn son and he would be in the third grade by the time you reached El Paso, which qualifies as primo Texas braggadocio.[4] A travel writer for some major newspaper voted Texas “the most irritating state.” He didn’t explain why, but it has a whiny undertone, don’t you think? Traffic? Cedar pollen? Bless his heart.

In the same general spirit, two friends who live in California told me last week that they can’t imagine how I tolerate living in Texas. That is both an uncanny coincidence — two people with the same observation — and less-than-fortuitous timing, since the western third of their state is under two feet of water and the eastern third is blanketed by six feet of snow. The California weather competes daily with the war in Ukraine for the lead story in the New York Times and Washington Post. The continuing deluges have given rise to a brand-spanking new meteorological term: “atmospheric river.” And let’s not forget earthquakes that can collapse double-decker freeways. No, thankee, I’ll take the copperheads and humidity.

Back to Texas: the Alamo and the Battle of San Jacinto live on eternally in the hearts of some die-hard Texas natives, including Ida Burke Rankin, now deceased. Her only child had the misfortune to be born in northwest Louisiana, just twenty-seven miles from the border of the promised land. The kid lost count of how many times Ida reminded her to “REMEMBER THE ALAMO!!!! Approximately fifteen minutes after her husband’s Shreveport funeral, Ida packed up and moved back to Texas. Her grandfather Burke had married a Trice. Both are featured in this narrative, eventually.

Sam Houston was undoubtedly the most famous Tennessee migrant to Texas, having become governor of the state. His reputation was launched by a decisive victory at the Battle of Jan Jacinto, where he commanded the Texian forces.[5] Texans later marked the battlefield with a monumental obelisk and stationed the Battleship Texas nearby, just in case Mexico had notions of a rematch. The San Jacinto monument is ten or eleven feet taller than the Washington monument. That was surely no accident, and is yet another in the endless list of reasons why everyone hates Texas. Besides which, ours has a 220-ton star on top.[6]

The Trices and Burkes played in vastly different ballparks than General Houston, of course, being pretty much forgotten to history except perhaps in Waco. The ones featured in this article left Wilson County, Tennessee at different times, although they undoubtedly knew each other’s families. Both the Trices and Burkes owned land on Spring Creek, a lovely little arm of the Cumberland River nestled among gently rolling hills on the south side of the river.

The first two Trices to arrive in Texas, so far as I know, were the brothers William Berry Trice and Sion B. Trice. They arrived in 1853. Here is what a local history book says about Berry:[7]

He “was born in Wilson county, Tennessee, in the year 1834. His father was a substantial farmer, but never accumulated much property. He was deprived of the advantage of an early training, and never attended school a day in his life.”

“Substantial farmer,” what hooey! Berry undoubtedly contributed that fiction. Truth is, the Wilson County Trices were basically subsistence farmers, as were the Burkes. Neither family accumulated any property other than the land they farmed. Berry’s biography continues:

“In the year 1853 he was convinced beyond a doubt that a good future awaited him, and wanting more latitude for his operations, he concluded to go west. He left home with thirty-five dollars, and accomplished, in forty-seven days, what very few young men would have thought of undertaking — a journey on foot from Wilson county, Tennessee, to Waco, Texas. He walked the entire distance. Immediately after his arrival here, instead of seeking the shade and waiting for something to turn up, he hired himself to drive a wagon at $12.50 per month.”

The article doesn’t say so, but my family oral history is that Berry’s brother Sion accompanied Berry on the walk to Texas, a distance of more than 800 miles. Their parents, Edward and Lilly Smith Trice, were still alive when they left. I’m betting Berry and Sion weren’t waiting around for a substantial inheritance, which — as it turns out — wasn’t in the offing. Edward and Lilly had nine children, including Berry, Sion, and my great-great grandfather Charles Foster Trice.

Berry and Sion were involved in the construction of the famous Brazos River bridge in Waco – the first suspension bridge west of the Mississippi[8] (more Texas braggadocio). Trice Brothers Brick and J. W. Mann did the brick work for the bridge, furnishing two million, seven hundred thousand bricks.[9] Berry and Sion became rich as sin in the process, ensuring funding for some impressive Trice monuments in Waco’s old Oakwood Cemetery.

Before making a fortune in bricks, Berry drove a wagon, cut and split rails, and worked in a sawmill. He was elected constable in 1855 and Justice of the Peace eight years later. When he was elected constable, he couldn’t even write his name.[10] His second wife was the widow of a former sheriff named Alf Twaddle, possibly the worst surname on the planet.

In the 1860 and 1870 census, Berry described himself as a “brick maker.” By 1880, he was a “farmer and banker.” At Berry’s death, he was president of Waco National Bank; he was then, or had been, a director. He was, according to The Handbook of Waco, “one of the wealthiest men in our community.” He owned five farms, although I am confident there was no dirt under his fingernails. Nor did Berry miss any meals: he weighed over 400 pounds when he died.[11] The local history book describes him colorfully:

” … Not only is he of great weight in financial circles, but his ponderosity amounts to four hundred and twenty-five pounds, and, in physique, he possesses more latitude and longitude than any man in the county. He is … surrounded with all the conveniences and comforts of life.”

Ponderosity! I am embarrassed for whoever wrote that. With respect to the comforts of life, the inventory of Berry’s estate included, among many other things, a telescope, a piano, and a gold-headed cane. In the hundreds of estate inventories I’ve seen, that is the one and only telescope.

I’m not sure what Sion did before he and Berry founded the Trice Brothers Brick Yard, or how much he weighed. He is also buried in the Oakwood Cemetery along with more Trices and Trice in-laws than I can count. There is a telling slip of paper among Sion’s probate records describing expenses incurred on behalf of his two daughters: a receipt for “tuition in music to Misses Beaulah and Hattie Trice from Apr. 18 to Oct 1st 1879 … 5 months at $10 per month.”[12] Sion wasn’t nearly as famous as Berry, but he clearly didn’t want for anything, either.

Coincidentally — or not — the first Burke who appeared in Waco found a temporary home with Berry Trice. William “Burks” was listed in the 1880 census in Berry’s household. He was twenty at the time. Farmer was his stated occupation, although I suspect he left Tennessee at least in part to escape farming. His full name was William Logan Burke, the first of a fistful of men in my family with that name.[13] He was my great-grandfather and the eldest son of Logan (full name Esom Logan Burke) and Harriet Munday Burke. Logan and Harriett also owned land on Spring Creek in Wilson County. I’m not sure exactly when William Logan Burke left home, but I’m afraid he bailed out on his widowed mother and four underage siblings after their father died. When Logan died in 1877, his eldest son was still only seventeen. I would bet he was still at home, though I have no evidence. By 1880, he was in Waco.

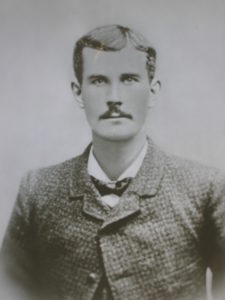

The first William Logan Burke wasn’t a farmer for long. He became “one of the early Sheriffs” of McClennan County, then a U.S. Marshall or Assistant Marshall. Owing to the plethora of men sharing his name among my Burke relatives, we call the first WLB “the Sheriff.” I know virtually nothing about him except that he was often absent from home. His daughter-in-law (Ida Huenefeld/Hannefield Burke) explained his frequent absences like so: “he was out chasing outlaws.” Here is a formal portrait of him, the only good likeness I have. Too bad he wasn’t wearing a badge.

The Sheriff married a Trice, although not one of the rich ones. She belonged to the third set of my family’s Tennessee migrants to Waco: Elizabeth (Betty) Morgan Trice. Her parents, Charles Foster Trice and Mary Ann Powell, also lived on Spring Creek in Wilson County. Foster was a blacksmith. Mary Ann was a quick-thinking lady who once outfitted him in a woman’s dress and bonnet, sitting him in a rocking chair in front of the fireplace, peeling potatoes, just before Union Army “recruiters” came to call.

Spring Creek wasn’t kind to Foster. He died in 1881 in a cave-in of the creek bank. There was a coroner’s inquest into his death, which was ruled an accident.[14] His land had to be sold because his personal estate was inadequate to pay debts. Foster didn’t make it to Waco, but his widow Mary Ann and eight children moved there some time between 1881 and 1886.

Mary Ann is buried in Waco’s Oakwood Cemetery along with the other Trices, Betty and the Sheriff, and Ida Hannefield Burke’s parents Ella Adalia Maier and John Henry Hannefield. Mary Ann died in 1928, when her great-granddaughter Ida Burke was eighteen. Ida heard the potato-peeling-dress-wearing story directly from the horse’s mouth, so to speak.

Mary Ann’s daughter Betty Morgan Trice Burke was a tiny redhead who could, according to my grandmother, “hold her liquor like a man.” Her only surviving child, the second William Logan Burke, was a dead ringer for his mother. Here she is, in a fabulous dress featuring elaborate ribbon trim, a brooch at her neck, and a fancy watch pinned to the dress.

The Sheriff died of tuberculosis in 1899, when the second William Logan Burke was eleven. The Sheriff’s widow, Betty Trice Burke, married a kind man named Sam Whaley in 1906, although she had been ill for a good while. She died just a few months after she married Sam, when her son was eighteen. Her obituary mentions both the Trice family’s elevated status in the community and the Sheriff. Her memorial in Oakwood Cemetery, a flat marker, is considerably more modest than Berry’s.

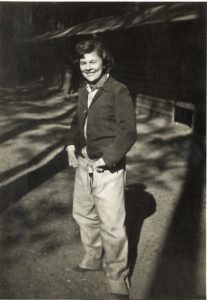

She had four children, but only one — her spitting image, my grandfather — survived her. Here he is as a young man:

“Gramps,” we cousins called him, was a genuine, Grade-A, certified Texas character, born in Waco in 1888. He went by W. L., or just “Billie.” I adored him, and vice versa. He taught me how to shoot a BB gun at a moving target by hanging the lid of a Folger’s can on a string from a tree branch. He gave me a fishing rod and reel, never used in my non-fishing family. Every time my grandparents came to Shreveport, he brought me some kind of critter. Baby chickens. Baby ducks. Goldfish. Once, he brought a pair of quail for which my father built a fabulous cage. Unfortunately, they launched into their “bob-WHITE!” calls each day at sunrise. They have surprisingly good lungs for such small birds. Neighbors registered complaints. One night, the quail mysteriously “escaped.” My father often said that he fully expected his father-in-law to bring me an elephant one day.

Sometime in the 1950s, Gramps had a pet wild turkey named Clyde. I am not making this up. When we were visiting my grandparents in Houston, we would all sit outside after dinner in those old uncomfortable slatted metal chairs when it was nice outside, meaning anything over 70 degrees. No air-conditioning in the 1950s. Clyde would sit on the arm of Gramps’s chair and apparently enjoy the conversation, looking at whomever was talking. Once, when we were driving back to Houston from Fredericksburg, Gramps abruptly pulled the car over to the side of the road beside a sorghum field, saying “I’m gonna get some of that good milo maize for my turkey.” Whereupon he climbed over the barbed-wire fence and grabbed a handful. My grandmother didn’t bat an eye, having known him since they were teenagers. I don’t know what became of Clyde, but I know he was spoiled rotten.

Gramps was a polo player and, after he was too old to play, a referee; a hunter who raised bird dogs, including a prizewinner named “April Showers;” a fisherman; and a spinner of tall tales. One of them made it into either the Houston Chronicle or the Post, I don’t know which. Granny cut it out and mailed it to my mother, with a penciled note saying “Your daddy in print with a big one.” It was in a column titled “The Outdoor Sportsman” by Bill Walker. Here is a transcription:

“A roaring gas flame in the big brick fireplace in the Cinco Ranch clubhouse warmed the spacious room and the several members of the Gulf Coast Field Trial Club who gathered there for coffee Saturday morning before the first cast in the shooting dog stake.

“Usually when veteran field trial followers get together the conversations turns to great dogs of yesteryears and this group was no exception.

“W. L. “BILLY” BURKE related one about an all-time favorite of ours — Navasota Shoals Jake.

“Burke and the late W. V. Bowles, owner of Ten Broeck’s Bonnett and Navasota Shoals Jake, were hunting birds in the Valley on one of those rare hot and sultry winter mornings. Jake pointed a covey several hundred yards from the two men and out in the open.

“BOWLES suggested they take their time approaching the pointing dog, since he was known to be very trustworthy. When the two hunters did not immediately move to Jake, the dog broke his point, backed away to the cool shade of a nearby tree and again pointed the birds.

“THE COVEY was still hovering in a briar thicket when Bowles and Burke arrived. Navasota Shoals Jake was still on point.

Here is Gramps in his 60s as a polo referee:

I should probably also include a picture or two of his daughter, Ida Burke Rankin, the die-hard Texan who admonished me to “Remember the Alamo!” They wouldn’t let women play polo in her day, of course, although I am confident she would have beat the heck out of everyone. Undoubtedly to show them, whoever “they” were, she used to ride her father’s polo ponies like a bat out of hell whenever she thought he wouldn’t find out. She once fell off on a blacktop road and said she couldn’t sit down for three days. She claims Gramps never knew, but I’ll bet he did. He was nobody’s fool.

And one more, when I was about three:

Next, I might have to write about Granny, a character in her own right.

See you on down the road.

Robin

[1] Here is a link to an article about the Battle of the Alamo by the reputable Texas State Historical Association, complete with images of Davy Crockett, William Barrett Travis, and James Bowie. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/alamo-battle-of-the

[2] There were either 31 or 32 or Tennesseans at the Alamo. An authoritative list has the same name twice, and it is unclear whether those names represent one or two men. See the list at this link: https://www.historicunioncounty.com/article/tennesseans-who-died-alamo

[3] For the record, 1,500 miles exaggerates both the length or width of Texas. It is 827 miles from Beaumont to El Paso on I-10, and about 850 from Texhoma, OK, on the OK-TX panhandle border, to McAllen on the Rio Grande. This is another reason people hate Texans: bragging about how big the state is.

[4] The math doesn’t audit on that bit of hyperbole, either. If mules or horses walk at 3 mph for 8-hour days, the journey would surely take less than six months even with interruptions.

[5] Here is a link to an article about the Battle of San Jacinto. It also has a fabulous picture of the San Jacinto monument. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/san-jacinto-battle-of

[6] See a closeup of the star and a photo of the monument here: https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/san-jacinto-monument-and-museum

[7] John Sleeper and J.C. Hutchins, The Handbook of Waco and McLennan County, Texas (Waco: Texian Press, 1972), article titled “William B. Trice.”

[8] Here is a photograph of the bridge, now a pedestrian walkway. https://www.loc.gov/resource/highsm.29747/?r=-0.163,-0.02,1.362,0.789,0

[9] Id., article titled “The Waco Suspension Bridge.”

[11] John M. Usry, early Waco Obituaries 1874 -1908 (Waco: Central Texas Genealogical Society, 1980), citing the July 16, 1884 issue of the Waco Daily Examiner at p. 2 col. 5, obituary of W. B. (Berry) Trice.

[12] Probate packet #671 at the courthouse in Waco, McLennan Co., TX.

[13] William Logan Burke, the escapee from Tennessee, was the first with that name. His only surviving child, my grandfather, was also William Logan Burke, who went by “W.L.” or just “Billie.” His only son was the third William Logan Burke, who was called Bill, or “the Kid” in his polo playing days. Bill’s elder son was known as “Little Bill.” He went by William Logan Burke III, although he was actually the fourth in the line. Little Bill’s brother Frank, who just goes by Burke, gave one of his sons that name. That makes five. My elder son’s name, by the way, is William Burke Willis, in honor of my wonderful grandfather.

[14] Tennessee State Library and Archives, Wilson Roll # B-1407, County Clerk (Loose Records Project) Box 59, Fld. 20 – Box 60, Fld 13. Vol: 1742-1962. This film contains Box 59, Folder 22, which contains an inquest into the death of C. F. Trice. I have a copy around here somewhere …