By Gary Noble Willis and Robin Rankin Willis

The coincidence part

We like to do genealogy trips to state archives, county courthouses, and so on. We drive rather than fly, and occasionally find ourselves off the beaten path or onto one that makes us scratch our heads. This happened once when we were traveling to Raleigh, NC from Houston, on I-20 going through Atlanta. We had to stop for gas, so Gary pulled off the freeway onto MLK Blvd. He immediately found a gas station, and I got out to stretch my legs with a quick walk. Heading up the hill, I found an historical marker about the Battle of Ezra Church — the one in the picture, above.

For the next two hours, I had a niggling feeling that I was supposed to know something about that battle: Ezra Church had grabbed my attention. Finally, I spit it out: “Gary, why does the battle of Ezra Church ring such a loud bell with me?”

Gary, a serious military and family historian, had a ready reply. “Because a member of your Estes family died there.”

What are the odds that we would wind up next to a battlefield where a relative fought and died, while getting gas in the middle of a huge metropolitan area?

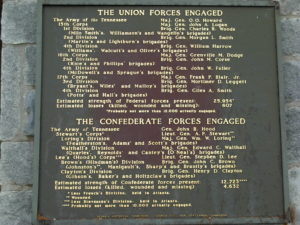

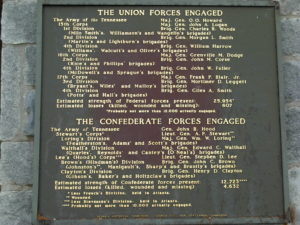

On our way home two weeks later, we pulled off again on MLK Blvd and took a tour of the battlefield, which is in the midst of a neighborhood. It is not even far enough from Atlanta to be called a suburb. There is a park there, with commemorative markers and the like. Here is one.

Notice the marker says that probably not more than 12,000 Union troops were actively engaged in that battle. Yet there were 4,600 Confederate dead. What sort of military madness was going on there, we wondered?

The article

When we got home, we researched the battle and jointly wrote an article about the three Estes brothers who were in Ham’s Cavalry, including the one Estes brother who fought and died at the Battle of Ezra Church. If you like history, especially Civil War history, you might like this article. I like it because, among other things, I found out from their war records that the three Estes brothers in Ham’s Cavalry had black hair and a fair complexion, just like their great-great-great nephew, my father.

Here is the article, which was originally published in “Estes Trails,” Vol. XXIII No. 3, Sept. 2005:

The Confederate Sons of Lyddal Bacon Estes Sr. and “Nancy” Ann Allen Winn Estes

Lyddal Bacon Estes Sr. (“LBE”) and “Nancy” Ann Allen Winn,[1] who married in Lunenburg County, Virginia on 10 March 1814, had five sons: (1) Benjamin Henderson Estes (“Henderson”), (2) John B. Estes, (3) Lyddal Bacon Estes Jr. ( “LBE Jr.”), (4) William Estes, and (5) Allen W. Estes. At least three of the five sons – Henderson, LBE Jr. and Allen – fought for the Confederacy, and this article is about them.[2]

Henderson and LBE Jr. served during 1861-1862 in an infantry regiment involved in the unsuccessful defense of Fort Donelson, Tennessee.[3] Beginning in 1863, the three Estes brothers all served as officers in Company A of Ham’s Cavalry. That unit was also known as the 1st Battalion, Mississippi State Cavalry, and then as Ham’s Cavalry Regiment after it transferred from state to Confederate service.[4] Company A was nicknamed the “Tishomingo Rangers” – indicating that the unit was formed in Tishomingo County, Mississippi and that many members of the unit may have lived there, as did the Estes family.[5] The three brothers’ military service records beginning in 1863 contain some interesting genealogical information for researchers on this Estes line, and also help to put a human face on what might otherwise be impersonal Civil War history.[6]

Infantry Service

B. H. Estes appears as a 3rd Lieutenant and 2nd Lieutenant with Company D of the 3rd Mississippi Infantry Regiment, and then as a 3rd Lieutenant of the 23rd Infantry Regiment, Company D.[7] The unit was originally raised as the 2nd Mississippi Infantry under Col. Davidson in August-September 1861 and sent to Kentucky, where it was known as the Third Regiment and, after November 1861, the Twenty-Third Regiment. The regiment was involved in the defense and surrender of Fort Donelson in February 1862, although some of the unit escaped. Captured members of the regiment were held at Springfield, Illinois, Indianapolis, Indiana and at Camp Douglas, Chicago, where a number died and are buried. Survivors were exchanged in the fall of 1862 and the regiment was reorganized and recruited replacements.[8]

LBE Jr. apparently served in the same unit. He (or some L. B. Estes, presumably the same man) is reported as serving as a Lieutenant in Company G of the 2nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment, part of Davidson’s command which became renumbered as the 3rd and then the 23rd.[9] Like his brother, we don’t know whether he was captured and exchanged, or escaped capture, at the surrender of the fort. In any event, both Henderson and LBE Jr. were available to serve in Ham’s Cavalry by March 1863.

It is possible that, after the prisoner exchange of 1862, both returned to their homes in Tishomingo County. By that time, Tishimingo and other northern Mississippi counties were outside Confederate control and beyond the reach of conscription or forced service. However, local partisan companies or so-called “state troops” were organized in these regions and sometimes operated without Confederate oversight. Often such troops were part-time soldiers, living at or near home and tending to their farms. That seems to have been the case with Ham’s Cavalry as originally organized.[10]

Henderson Estes (12 Dec. 1815 – 6 Jan. 1897)[11]

After 1862, the Civil War file for Henderson (who is shown consistently in the file as “Captain B. H. Estes”) indicates that he enlisted twice: this was not unusual, because soldiers frequently enlisted for a limited term and then “re-upped” when the initial term had expired. In most Confederate records, the name of the officer who enlisted or re-enlisted the soldier is also stated in the file. What is unusual in Henderson’s case is that his file indicates that he enlisted himself for his first term of service. Stated another way, the file shows that Capt. B. H. Estes was the enlisting officer for Capt. B. H. Estes. This suggests that Henderson may have been, and probably was, the person who organized the Tishomingo Rangers. This is supported by the fact that he signed one of the muster rolls as company commander, since it was common for an organizer to be a company leader. Further, since he was in his late forties when the war broke out, Henderson would have been a logical candidate to organize a unit that was presumably composed primarily of younger men. He was also from a relatively prosperous family, which was a virtual prerequisite for organizing a unit: the organizer frequently, if not usually, helped outfit the unit he recruited.

Henderson enlisted himself and his brothers LBE Jr. and Allen W. Estes in Kossuth, Mississippi on March 10, year unstated, for a term of 12 months. That enlistment must have occurred by at least March 1863, because Henderson appears on the Company A muster roll records for September 18, 1863 through April 30, 1864. A March 1863 enlistment would also be consistent with the dates of his earlier infantry service. The record indicates that Henderson enlisted for a second time on January 20, 1864 in Richmond, Virginia. No enlistment term is stated. Henderson was not actually in Richmond on that date, since Ham’s Regiment never participated in any battles in Virginia. It is likely that Richmond was given as the place of re-enlistment for administrative simplicity, since the troop was in the field at the time and was possibly re-enlisted en masse. Shortly thereafter, on May 5, 1864, Ham’s Cavalry transferred from Mississippi state service to Confederate service. A descriptive list of Company A, Ham’s Cavalry Regiment, notes that Henderson was 5’7″, with blue eyes, black hair, and a fair complexion.[12] He is described as a farmer, born in Virginia, age 48, which is consistent with the census records in which Henderson appears as a head of household.[13]

LBE Jr. (Sept. 20, 1826 – Apr. 18, 1903)[14]

LBE Jr., a Second Lieutenant, also enlisted on May 10 for a term of twelve months, by enlisting officer Capt. B. H. Estes. The year was not stated but, like Henderson, it was probably 1863. LBE Jr.’s record states that he was mustered into Confederate service on May 5, 1864 by Capt. L. D. Sandidge for the duration of the war. His file, like Henderson’s, records his appearance on the muster roll of Company A from at least September 18, 1863 through April 30, 1864. LBE Jr.’s file also indicates that Company A was in Tupelo, Mississippi as of 15 December, 1863. Like his brother Henderson, LBE Jr. stated that he was a farmer. He gave Tennessee as his place of birth and his age as 37. LBE Jr. was almost certainly born in McNairy County, Tennessee, because that is where LBE Sr. and family appeared in the 1830 federal census. LBE Jr. re-enlisted, along with Henderson, on January 20, 1864. He appears on the descriptive list as 5’6″, age 37, blue eyes, dark hair, and fair complexion.

Allen W. Estes (about 1832 – July 29, 1864)[15]

Allen’s service record states that his name appears on a register of officers and soldiers of the Confederate Army who were killed in battle or died of wounds or disease. The youngest of the three brothers, Allen was age 32 when he enlisted. He was the tallest, at 5’8″, and had the same black hair, blue eyes, and fair complexion as his elder brothers. He was also a farmer, and, like LBE Jr., born in Tennessee, presumably McNairy County. His file states that Allen had his own gun; his brothers probably did as well, although only Allen’s file mentions that matter. Each of the three also undoubtedly had his own horse, which was a requirement for a member of a cavalry unit.

Like his brothers, Allen enlisted at Kossuth on March 10 (presumably 1863) for a period of 12 months. His rank at enlistment was Second Sergeant, and he appeared on the Company A muster rolls with that rank for July 8 through January 20, 1864, when the unit was transferred from state to Confederate service. On May 5, 1864, he appeared in his file for the first time as a Captain. Duration of his enlistment: “for the war,” although another record in his file indicates that Allen enlisted for a period of three years. The length of his enlistment was moot, however, because Allen died on July 29, 1864, in a hospital in Atlanta, Georgia. Allen left a widow Josephine (neé Jobe) and a son Joseph, born about 1862.[16]

Ham’s Cavalry

Ham’s Cavalry was active in various conflicts in Mississippi, Tennessee and Alabama. The regiment participated with Gholson’s Brigade in three attacks on July 6 and 7, 1864, in an unsuccessful attempt to cut off the retreat of Union forces from Jackson toward Vicksburg, Mississippi.[17] Additionally, the unit was almost certainly involved in the battle at Tupelo on the 14th and 15th of July, 1864. In that engagement, Confederate Generals Stephen D. Lee and Nathan Bedford Forrest, with about 8,000 troops, attacked Union General A. J. Smith’s federal force of about 14,000 in a series of uncoordinated and piecemeal assaults. The Confederates were defeated with heavy casualties.[18] Battlefield maps clearly reveal the superior defensive position occupied by the Union forces on a ridge about one mile west of Tupelo.[19]

Atlanta is approximately 270 miles from Tupelo, and ten days after the battle at Tupelo, Ham’s Cavalry was again with Gholson’s Brigade in the lines at Atlanta, dismounted – that is, fighting as infantry rather than as cavalry. This recounting of the unit’s participation in that battle is from Dunbar Rowland’s Military History of Mississippi, 1803 – 1898:

“On July 28th [1864], fighting west of Atlanta, [Ham’s Cavalry] made a desperate charge on the breastworks in the woods, and sustained heavy losses. Colonel Ham was mortally wounded, and died July 30. Captain Estes, of Company A, and Lieutenant Winters, commanding Company D, were killed.”[20]

The Captain Estes referenced by Rowland was obviously Allen, who died the following day in an Atlanta hospital. Another account refers to this engagement as the Battle of Ezra Church (or the Battle of the Poor House), and indicates serious errors in judgment and leadership by some of the commanding officers. Confederate commander John B. Hood had ordered Generals Stephen D. Lee (who had also been present at the battle of Tupelo) and Alexander P. Stewart, each with two divisions, to intercept an advancing Union force under General O. O. Howard in order to prevent the federal troops from cutting the last western rail line leading to Atlanta:

“[Hood] instructed the generals not to engage in a battle, just halt the Federals’ advance down the Lick Skillet Road. He was preparing for a July 29 flank attack against Howard. Lee, however, violated orders. At 12:30 p.m. on July 28 his troops assaulted Howard at Ezra Church. Howard was prepared … and repulsed Lee’s first attack. Stewart launched a series of frontal attacks over the same ground … The Federals repulsed the attacks and inflicted heavy losses…”[21]

A battlefield map shows that Howard’s Union forces, located about three miles west of the Atlanta railroad depot, occupied a strong defensive position on a ridge line behind a rail barricade.[22] Attacking in such circumstances was not only contrary to express orders, it was virtually suicidal.[23] Estimated casualties: 562 U.S., 3,000 Confederate.[24] A marker at the battlefield states that Brantly’s Brigade of Mississipians on the extreme left of the Confederate forces made it over the log barricades of the 83rd Indiana Regiment. However, they were swept back by a counterattack. Ham’s dismounted cavalry was probably part of this attack, and this (we speculate) may be where Captain Allan Estes fell.

We do not, of course, want to honor the Confederate army, which was fighting to maintain slavery. We can nevertheless honor individuals who fought bravely for either side. Ironically, the family of Allen Estes, who died in that horrible war, did not own slaves.

By the following spring, whatever was left of Ham’s Cavalry was assigned to Armstrong’s Brigade as part of Ashcraft’s Consolidated Mississippi Cavalry.[25] According to Rowland’s History:

“The command made a gallant fight against odds, in the works at Selma, Alabama, April 2, 1865. Here a considerable number were killed, wounded or captured … The officers and men were finally paroled in May, 1865, under the capitulation of Lieut. Gen. Richard Taylor, May 4.”[26]

There is no indication in their individual military records as to when or where Henderson and LBE Jr. ended their Confederate service. However, LBE Jr.’s file expressly states that he enlisted for the duration of the war, suggesting that he was probably among those paroled at Selma. Given the history of the unit, it seems amazing that two of the three Estes brothers managed to survive.

Both LBE Jr. and Henderson Estes returned to Tishomingo County after the war. Henderson appeared in the records there as a Justice of the Peace in the late 1860s[27] By 1870, his mother Nancy had died, and he had moved his family to McLennan County, Texas.[28] By 1880, LBE Jr. had joined Henderson and their sister, Martha Estes Swain, in McLennan County.[29] LBE Jr. and his sister Martha are buried in the Fletcher Cemetery in Rosenthal, McLennan County; Henderson is buried at the Robinson Cemetery, also in McLennan County.[30]

© 2005 by Robin Rankin Willis & Gary Noble Willis.

[1] Nancy did not have four names, of course. She went by Nancy, which was most likely a nickname for Ann. She appeared in the records as Ann Allen Winn (Lunenburg Will Book 6: 204, FHL microfilm 32,381, will of her father Benjamin Winn, naming among his other children Ann Allen Winn), Nancy Allen Winn (Lunenburg Guardian Accounts 1798 – 1810 at 136, FHL microfilm 32,419, account naming Nancy Allen Winn and other orphans of Benjamin Winn), and Nancy A. Winn (numerous Tishomingo Co., MS records, e.g., Tishomingo probate Vol. C: 391, FHL Microfilm 895,897, bond for administrators of the estate of Lyddal B. Estes).

[2] We haven’t found any record of Civil War service for the other two sons, John B. Estes and William Estes. John left Tishomingo before 19 Aug 1853, when he and his wife Avy or Amy Ann Somers executed a deed from Nacogdoches Co., TX. Tishomingo DB Q: 305, FHL Microfilm 95,878. John appeared in the 1860 and 1870 U.S. census for Nacogdoches Co. but not thereafter. William Estes had already left Tishomingo by at least 18 Feb 1853, when he executed a general power of attorney in favor of Benjamin H. Estes. Tishomingo DB Q: 307, FHL Microfilm 895,878. The power of attorney recites that William was then a resident of San Francisco Co., CA.

[3] H. Grady Howell, For Dixie Land, I’ll Take My Stand (Madison, MS: Chickasaw Bayou Press, 1998) at 830-31.

[4] http://www.mississippiscv.org/MS_Units/Hams_MS-CAV.htm.

[5] LBE Sr. and his family appeared in Tishomingo in the 1837 and 1845 Mississippi state census and the 1840 U.S. census. LBE Sr.’s widow Nancy appeared in the 1850 and 1860 census for Tishomingo Co. The service records for all three Estes brothers state that they originally enlisted in Kossuth, MS, now located in Alcorn Co. (created from Tishomingo in 1871). All the companies in Ham’s Cavalry were recruited from Tishomingo, Yalobusha, Itawamba and Noxubee Counties. http://www.mississippiscv.org/MS_Units/Hams_MS_CAV.htm

[6] Unless expressly noted otherwise, the information in this article is from the National Archives & Records Administration’s military service records for B. H. Estes, L. B. Estes, and A. W. Estes. These Civil War files for the Estes brothers cover service from 1863, but not the earlier service referenced elsewhere.

[7] Howell at 830; www.mississippiscv.org/MS_Units/23rd_MS_INF.htm, which provides information from Dunbar Rowland’s Military History of Mississippi, 1803-1898.

[8] See www.mississippiscv.org/MS_Units/23rd_MS_INF.htm, information from Dunbar Rowland’s Military History of Mississippi, 1803-1898.

[9] Howell at 831. An L. B. Estes is also reported as having served as a non-commissioned officer (a corporal) in Company D of the 32nd Infantry Regiment. Based on the dates of formation of this unit and the 2nd Mississippi, it is likely these are two different people. Since Henderson Estes was in the same command, it is likely that Lt. LBE rather than Corporal LBE is the son of LBE Sr. and Nancy Estes.

[10] See www.mississippiscv.orgMS_Units/Hams_1st_MS_ST_CAV.htm.

[11] Central Texas Genealogical Society, Inc., McLennan County, Texas Cemetery Records, Volume 2 (Waco, Texas: 1965) at 154 (abstract of tombstone of Benjamin Estes in the Robinson Cemetery). He is listed in the 1840 census as “Henderson Estes,” see U.S. Census, Tishomingo Co., MS, p. 231.

[12] The NARA record indicates that the descriptive list is contained in an original record located in the office of the Director of Archives and History, Jackson, MS, M.S. 938010.

[13] 1860 U.S. census, Tishomingo Co., MS, Kossuth P.O., dwelling 606, (Benj. H. Estes, age 43, farmer, b. VA); 1870 U.S. census, McLennan Co., TX, Waco, dwelling 755 (B. H. Estes, age 55, farmer, b. VA); 1880 U.S. Census, Brown Co., TX, Dist. 27 (Benjamin Estes, 64, b. VA, parents b. VA).

[14] Central Texas Genealogical Society, Inc., McLennan County, Texas Cemetery Records, Volume 2 (Waco, Texas: 1965) (abstract of tombstone of Lyddal Bacon Estes in the Fletcher Cemetery, Rosenthal).

[15] See 1860 U.S. Census, Tishomingo Co., MS, Boneyard P.O., dwelling 583 (listing for Nancy A. Estes and Allen Estes, age 27, thus born about 1833); service record of A. W. Estes (age 32 at enlistment in 1863, thus born about 1831).

[16] Irene Barnes, Marriages of Old Tishomingo County, Mississippi, Volumes I and II (Iuka, MS: 1978) (marriage of Josephine Jobe and W. A. Estes (sic, Allen W.), Oct. 1859; marriage of Mrs. Josephine Estes and G. L. Leggett, August 1868). Grimmadge Leggett and wife Josephine appeared in the 1880 census, Alcorn Co. MS with his stepson “Jos. Ester” [sic], only child of Allen W. Estes; see also 1900 census, Alcorn Co., MS.

[17] See http://www.mississippiscv.org/MS_Units/Hams_MS_CAV.htm.

[18] See http://www.decades.com/CivilWar/Battles/ms015.htm. Casualties estimated at 648 US, 1,300 CS.

[19] Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, DC: (Government Printing Office, 1891-1895, reprinted 1983 by Arno Press, Inc. and Crown Publishers , Inc. and in 2003 by Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc.), at p. 167, Plate 63 – 2.

[20] See http://www.mississippiscv.org/MS_Units/Hams_MS_CAV.htm.

[21] See http://wwwhttp://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/civwar/html/

[22] See Atlas (note 14) at p. 153, Plate 56 – 7.

[23] General Lee also made serious military errors at Tupelo, committing understrength forces piecemeal against federal troops occupying a solid defensive position. He was obviously well-regarded, because he was the Confederacy’s youngest Lt. General and was the commander of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi and East Louisiana.

[24] See . Another source estimates casualties at 700 U.S. 4,642 CS. http://wwwhttp://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/civwar/html/.

[25] Howell at 213-214, listing Henderson Estes, Captain, and Toney Estes (LBE Jr.’s nickname), First Lieutenant, Company A, Eleventh Mississippi Cavalry (Ashcraft’s).

[26] See http://www.mississippiscv.org/MS_Units/Hams_MS_CAV.htm.

[27] Fan A. Cochran, History of Old Tishomingo County, Territory of Mississippi (Canton, OH: Barnhart Printing Co., 1972)

[28] Nancy does not appear in the 1870 census. An 1872 deed from Henderson to LBE Jr. recites that Nancy was deceased and that Henderson resided in McLennan Co., Texas. Tishomingo DB 2: 590, FHL microfilm 0,895,389.

[29] 1880 U.S. Census, McLennan Co., TX, p. 261 (listing for Lydal P. [sic] Estes and family).

[30] John M. Usry, Fall and Puckett Funeral Records (Waco, Texas: Central Texas Genealogical Society, 1974); McLennan County, Texas Cemetery Records, Volume 2.