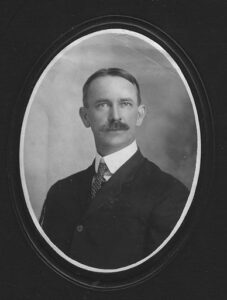

When we left Dr. Willis in 1899 in a Field of Dreams Part I, he had just remarried after the untimely death of his first wife Mary E. McMaster. Their two children were Mary Catherine, age eight, and Harry McMaster, age six, when Dr. Willis remarried. Jessie Sensor, his new wife, was only eighteen, a very young stepmother for these two! She was the daughter of The Reverend George Guyer Senser and Julia Frances Mendenhall.[1]

During the year between his wife’s death and his remarriage, surely family or friends helped Henry care for the children. The kids lived at Henry’s home on Second Street. Their maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Grace McMaster, lived close by in Pocomoke City on Market Street between First and Second. Henry also had a live-in cook in the household, Annie Marshall. Regardless, the trauma of losing Mary had to have been extremely painful for Henry and their children.

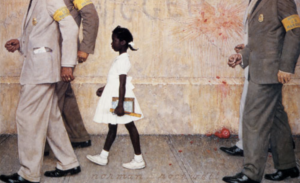

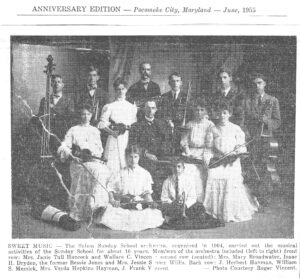

Jessie joined the family and settled into the Willis home on Second Street. They lived there for another nine years. The 1900 census lists the four Willis family members and Annie.[2] The Willises began attending church at the Salem Methodist Church at 500 Second Street Jessie’s father preached there on a rotating basis. Jessie was active in the church, as she had been throughout her life. She played the violin in the Salem Sunday School Orchestra.

A photo of the group published in the local paper shows her seated at the far right. According to the paper, the ensemble organized in 1904 and played for about ten years.[3] Henry and Jessie’s first child was also born in 1904, a daughter they named Grace after Jessie’s younger sister.

A photo of the group published in the local paper shows her seated at the far right. According to the paper, the ensemble organized in 1904 and played for about ten years.[3] Henry and Jessie’s first child was also born in 1904, a daughter they named Grace after Jessie’s younger sister.

In 1908, the family moved to Wilmington, Delaware. Records do not indicate why the family relocated. Dr. Willis seemed to be doing well in Pocomoke City. He had served one term as a commissioner of the Orphan’s Court in Worcester.[4] He and Jessie owned their home and an office building. Initially, the children’s grandparents were close by. Elizabeth McMaster lived in town and the Sensors were only 20 miles distant. That support system disappeared when Elizabeth McMaster died, and several years later the Methodist Church reassigned George Sensor to churches in New Jersey.[5] Maybe the lure of the larger city enticed Jessie and Henry to move. Moving closer to Jessie’s parents may also have been a factor. Wilmington is about 35 miles from Camden and Wenonah, New Jersey, where Reverend Sensor was newly assigned. The extended family took another hit, however, when Rev. Sensor died in 1913. Whatever the reasoning at the time, Henry and Jessie sold their home in Pocomoke and moved.[6]

Financial Mystery

The family’s financial situation is a mystery. Henry inherited several hundreddollars from his father’s and grandfather’s estates.[7]He purchased property on Second Street in Pocomoke City for $350 in 1890. He and Jessie sold it for $2,100. That would have been a nice profit except that it was mortgaged for $1,500. The net cash to the family was only $600 less any fees. Henry and Jessie did not have enough money to buy a house in Wilmington, so they rented.

It appears that Dr. Willis had been increasingly in debt in Worcester County. Deed records show that only months after purchasing the home in Pocomoke, he borrowed money against it. Further, he refinanced the debt in larger amounts over the years.[8] When his first wife inherited an interest in property from her father, they mortgaged that as well, even before they owned part of it outright. They refinanced that property several times at increasing amounts.[9] There is no record of how Henry used the borrowed money. Did he try to start a drug store, as suggested by his purchase of soda fountain equipment? One mortgage of the office building that was part of the inherited McMaster property indicated it was occupied by, and presumably rented to, a fish and oyster dealer.[10]There should have been some income from that rental. Interestingly, deed records do not show Henry and Jessie ever selling the McMaster property. Was it repossessed for nonpayment of debt? Whatever the actual state of their finances, Henry and Jessie never bought a home in Wilmington. They lived in rented houses for the rest of their lives.

Wilmington

Dr. Willis worked as a general practitioner in Wilmington. He received specialist training in eye, ear, nose and throat diseases and was for several years the city vaccine physician for the southeastern district. Jessie worked as a secretary and pastor’s assistant at Harrison Street Methodist Church a short distance from their home(s). She became Superintendent of the Beginners Department of the Church School and staged many religious productions by the church youth. We can assume her income helped maintain the household. Family legend states that Dr. Willis sometimes took payment in kind from his patients, e.g., a chicken or two instead of currency.

Henry’s mother, Emily R. Willis moved to Wilmington from Preston by at least 1909 and lived with her son’s family until her death in 1921.[11] Emily apparently took good care of her money and probably helped with household expenses. Her personal property estate in 1921 amounted to almost $6,500, all in bank deposits or a secured loan. Henry and his sister Mary each inherited about $2,700 after expenses.[12]

Tragically, the couple’s daughter Grace died of meningitis at the age of five in 1909.[13] Henry and Jessie soon adopted a child about the same age, Katheryn, whom everyone called Kitty. In 1916, Jessie gave birth to a son, Noble Sensor Willis, who was a full generation younger than his half-sister Mary. Mary was still listed in the household in the 1920 Federal Census at age 28 and worked as a secretary.[14]

Mary Catherine Willis

Mary Willis never married. She worked most of her life for the YWCA. In 1916, she attended a reunion of The McMaster Clan in America, in Ashbury Park, New Jersey. Her uncle John S. McMaster organized this national group after extensive research on the family’s Scottish roots.[15] The McMaster Clan elected her Foreign Secretary in 1920.

At the time, she was headed for Peking, China, as a secretary for The Language School, a missionary group sponsored by the YWCA. Her 1920 passport covered visits to Hong Kong, China and Japan.[16] A McMaster family history book lists both Mary and Harry with a permanent address in Wilmington, Delaware.[17] Mary returned from China to the United States before WWII broke out and continued working for the YWCA. She retired in St. Petersburg, Florida, where she died 29 Sep 1966. Mary is buried in the family plot at Silverbrook Cemetery, Wilmington, Delaware.[18]

Harry McMaster Willis

Harry Willis left Wilmington in 1917 to join the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, the precursor organization of the Army Air Corps.[19] He was a sergeant stationed in Wichita Falls, Texas, in 1918 when he married Margaret Allmond, a native of Wilmington.[20] She was the daughter of Dr. Charles M. and Emma Allmond. We can easily speculate that the doctors Willis and Allmond knew each other.

Harry and Margaret were married in Wichita Falls rather than Wilmington. Dr. Allmond accompanied his daughter on probably a two-day train trip from Wilmington to Wichita Falls for the wedding.[21] After being discharged from the service, Harry and Margaret moved back to Wilmington where he became an insurance agent. His listing with the McMaster Clan in 1920 showed him serving with 198th Aero Squadron, but with an address in Wilmington.[22]

Harry and Margaret raised two daughters, Margaret and Emma May, who married two Larson brothers. The young women were wed several years apart in the home of their grandparents, Dr. and Mrs. Allmond, by the pastor at Second Baptist Church. Harry’s wife Margaret died in 1967. Harry subsequently married Virginia Baker Borton, widow of Everett E. Borton. Harry died in Wilmington in 1974 and Virginia in 1981.

Part III

While his elder children were becoming independent, Dr. Willis’s health began to fail. He died of heart disease 11 April 1926.[23]Widow Jessie was left to raise eleven year old Noble Sensor Willis with only her income from working at the church. How she did that will have to wait for the third part of this family story.

One hint about what is to come — Harry’s stint with the Air Corps in World War I likely influenced the direction his young half-brother, Noble, took before World War II. Noble graduated from Duke University into the teeth of the depression in 1939. Unable to find a job that would use his new college degree, he enlisted in the Air Corps. Did Harry’s prior service have anything to do with that decision? We do not know, but it seems logical that it would. More to come.

______

A summary descendancy chart will help picture this family –

Henry Noble Willis (1865 – 1926)

Married 1st Mary E. McMaster (1867 – 1898)

Children:

Mary Catherine Willis (1891 – 1966)

Harry McMaster Willis (1893 – 1974)

Married 1st Margaret Lobdell Allmond (1896 – 1967)

Married 2nd Virginia Baker Borton ( – 1981)

Married 2nd Jessie Sensor (1881 – 1937)

Children:

Grace Willis (1904 – 1909)

Katheryn Willis (1905 – 1972)

Noble Sensor Willis (1916 – 1969)

[1] Several sources online give Jessie Sensor and her sister Grace the middle name Mendenhall, but I have found no evidence supporting either. In fact, some census records show their brothers with middle names or initials but not the two girls.

[2] 1900 Federal Census for Worcester Co., MD, Pocomoke City, page 23B, Second Street, dwelling # 80:

Dr. Henry N. Willis, 34, b Dec 1865, married 1 year, b MD; Jessie S. Willis, 19, b Jan 1881, married 1 year, b NEB; Mary C. Willis, 8, b Jul 1891, MD; Harry M. Willis, 6, b Jul 1893, MD; Annie Marshall, cook, 32, b 1868 VA

[3] The photo appeared in the 1955 Anniversary Edition of the local newspaper, the “Worcester Democrat,” copy of the clipping in possession of the author.

[4] Obituary newspaper clipping in possession of the author.

[5] Elizabeth Grace McMaster died in 1903 per tombstone on Find-A-Grave

[6] Worcester County Deed Book OCD 2:29 – 26 Jun 1908, Henry N. and Jessie S. Willis sell the Home Lot for $2,100

[7] Caroline County Deed Book ECF 61:369, 7 Dec 1894 – James S. Willis purchased lands of Zachariah Willis from his siblings or their heirs for $200 each. With sibling Henry F Willis deceased, his widow Emily R. Willis and children Mary W. Clark and Henry N. Willis shared the proceeds. Emily was apparently living with her daughter; both their signatures were notarized on the same document in Sussex County, Delaware.

[8] Worcester County Deed Book entries related to the Home Lot – FHP 1:116 – Henry N. Willis purchases for $350 in Sep 1890; FHP 1:275 – borrowed $500 in January 1891; FHP 1:310 – borrowed another $500 in February 1891; FHP 5:403 – borrowed $1,400 in October 1894 to refinance, netted $400; FHP 6:482 – borrowed $1,500 in July 1895 to refinance, netted $100.

[9] Worcester County Deed Book entries related to the Office Lot – FHP 1:202 – Elizabeth Grace McMaster gifts property to her four children in Dec 1890; FHP 3:535 – borrowed $600 secured by ¼ undivided interest in March 1893; FHP 4:524 – siblings gift the Office Lot to Mary E. Willis in December 1893; FHP 5:320 – borrowed $1,500 in July 1894 to refinance, netted $900; FHP 9:116 – borrowed $1,800 in Feb 1897 to refinance, netted $300.

[10] Worchester County Deed Book FHP 12:239 – 13 May 1899, Henry Willis borrowed $80 to be repaid at the rate of $20 every three months secured by the office building occupied by James W. Bonnefield [sic Bonneville] who appears in the 1900 census as a fish and oyster dealer.

[11] The 1909 City Directory for Wilmington lists the members of the household at 320 S. Heald Street as Henry N. Willis, Jessie S. Willis, Mary C. Willis, Harry W [sic M] Willis, and Emily R. Willis. It does not show a separate business address for Dr. Willis indicating he may have been seeing patients in his home. The 1910 Federal Census shows the same residents but lists the address as 315 S. Heald.

[12] Orphan’s Court of Caroline County, Maryland, Probate Records of the Estate of Emily P. Willis, died 13 Feb 1921, total personal property $6,452.41, net after expenses $5,407.52, distributed to each Henry N. Willis and Mary W. Clark $2,703.76.

[13] Return of a Death in the City of Wilmington, Grace Willis, 11 May 1909, Meningitis, born MD, Heald and New Castle Street.

[14] 1920 Federal Census for Wilmington shows the household at 703 West Tenth Street; Henry N. Willis, 54, physician; Jessie S, 38; Mary C., 28, secretary YWCA; Catherine [sic, Katheryn], 18; Noble, 3½; Emily P. 86.

[15] McMaster, Fitz Hugh, The History of the MacMaster-McMaster Family, The State Company, Columbia, South Carolina, 1926, 43.

[16] Passport application

[17] McMaster, 106. Miss Mary Clarke [sic Catherine] Willis, 919 Adams Street, Wilmington, Del. Born July 9, 1891, Pocomoke City, Md.; niece of John S. McMaster. The listing incorrectly states her middle name as Clarke rather than Catherine.

[18] Silverbrook Cemetery Records, Wilmington, Delaware, p 234 – Old Book; Lot #4 1/2, Section M, Deed # 418, Burial 16350, Grave 6, Mary C. Willis, 75 yrs., 10/4/66

[19] Delaware World War I Servicemen’s Records, 1917-1919, on Ancestry, Harry McMaster Willis, age 24, service date 8 Nov 1917.

[20] Wilmington Morning News 11 Oct 1918, page 12, at Newspapers.com. Sergeant Harry M. Willis married Margaret Lobdell Allmond on 30 Sep 1918 in Wichita Falls, Texas

[21] Undated newspaper clipping on Ancestry. Likely, Wilmington Morning News, Sunday, 29 Sep 1918. Also, the 1909 Wilmington City Directory lists Charles M. Allmond physician and druggist at 627 Market with a home at 914 West Street. Margaret L. Allmond is not listed in the directory. She is listed as 14 years old in the 1910 Federal Census.

[22] McMaster, 107. Harry McMaster Willis, 919 Adams Street, Wilmington, Del. Born July 27 1893 at Pocomoke City, Md.; nephew of John S. McMaster; member of 198th Aero Squadron.

[23] State of Delaware Death Certificate No. 1274, HN Willis, MD, 11 April 1926 at 7 a.m., 1215 W. 9th Street, Wilmington, Del. Cause of death myocarditis