I need help with John Burke. The problem with John calls for the ability to look at facts in creative ways and do some outside-the-box critical thinking. I’m more of a two-plus-two-equals-four kind of person, and my linear logic is not working well. I hope anyone with ideas will leave a comment. The issue is what to make of a family legend saying that John Burke’s older brother and his family, with whom John was migrating, were killed by Native Americans. It matters because it is part of a larger issue: where was John Burke’s family of origin, and when?

The massacre legend comes from the second of two written family histories about John Burke. I posted an article on 8/11/17 about the first history, a document written by John Burke’s great-grandson Victor Moulder — Part 1 of this series. The second history is titled “Burke Family in Tennesse [sic] and Kentucky by Victor and Geo. B. Moulder 1946.” George and Victor were brothers who had a good bit to say, most of which I will defer for a later article.

The massacre story – if taken literally with respect to time and place – is not consistent with historical facts. Of course, every genealogist who has dealt with oral family history legends knows that they are rarely 100% factually correct. Nevertheless, they virtually always contain an element of truth, or at least point toward some truth. So far, I have been unable to figure out the “true facts” to which the massacre story points.

Here is the relevant part of the Moulders’ story:

“John Burke … migrated [from Virginia] at the age of 14 to the Upper Yadkin River Country, North Carolina with an older brother and family who were killed by Indians … joined a company of immigrants to Tennessee, walked and worked his way as a cobbler.”

To place the timing of the story, the Moulders say John Burke was born in 1783. That date is consistent with the 1820 and 1830 censuses, which show John as having been born during 1780 to 1790.[1] A birth date in 1783 would put the date of the Burke family migration at 1797. Glossing over the precise dates, the gist of the story is that a teenage John Burke’s older brother and his family were killed by Native Americans in the late 1790s in the Upper Yadkin River Valley.

Either the date, the location, or both must be incorrect, because there weren’t any hostilities between Native Americans and European settlers in the Upper Yadkin River Valley in the 1790s. At least I haven’t been able to find any.

At this point, we need briefly to address some geography and Native American history. This is emphatically not a scholarly treatment by any stretch of the imagination, so please alert me to anything that doesn’t jibe with what you know.

First, location: the Upper Yadkin River Valley

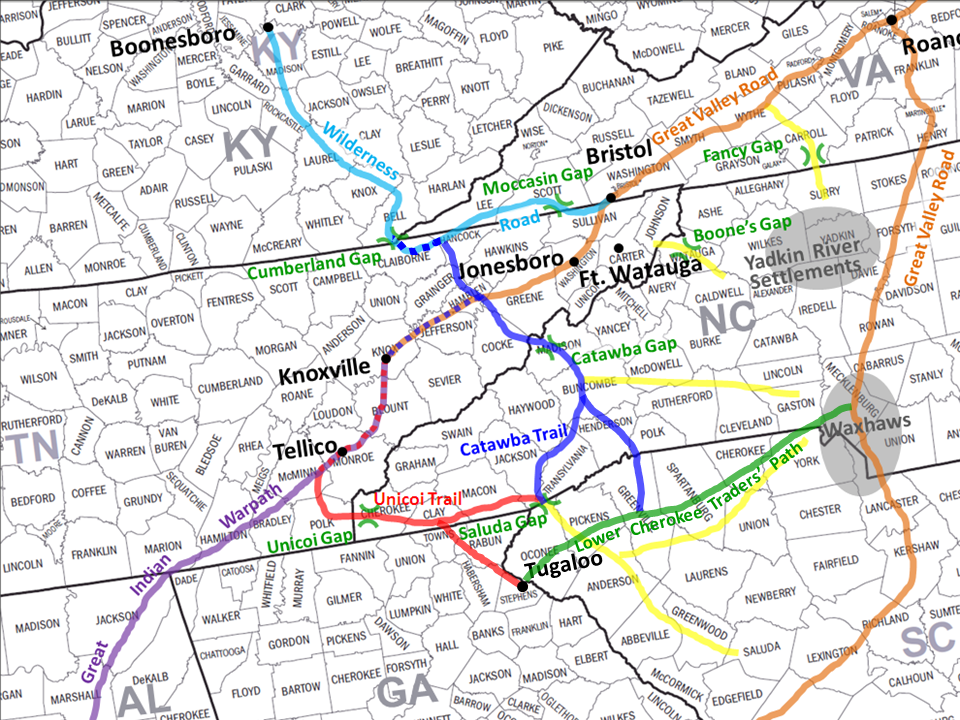

The Yadkin River roughly bisects North Carolina, flowing generally from north to south into South Carolina, where it becomes the Pee Dee River. Here is a map of some colonial migration routes in North Carolina which highlights in the upper gray circle the “Yadkin River Settlements.”

The area includes parts of current NC counties of Wilkes, Surry, Yadkin, Forsyth, Davie, Iredell and a sliver of Alexander. As of 1790 (before several of those counties were created), the relevant counties would have been Wilkes, Surry, Iredell and Rowan.

Native American players

Google was unable to answer my simple-minded question, “what hostile Native American tribes lived in the Upper Yadkin River Valley in the late 1700s?” Deprived of an easy answer, I started at the very beginning, with a map of Native American tribe locations in North Carolina before European settlers appeared.

The map shows three tribes whose range probably included part of the upper Yadkin River valley, although not necessarily during the 1790s: the Catawba, Cheraw, and Keyauwee. The map also shows the Cherokee in western NC in the area of the Blue Ridge Mountains, just a bit west of the Yadkin River Valley.

None of those first three tribes threatened settlers in the Upper Yadkin Valley in the late 1700s, so far as I have been able to find.

The Catawba, who were friendly to European settlers, lived prior to the Revolution in the Catabaw River Valley around Charlotte, NC and into South Carolina. They were virtually extinct by the end of the 18th century, decimated in large part by smallpox.[2]

By the 1720s, the Cheraw (or Saura) were located on the upper Pee Dee near the NC/SC border, well south of the Upper Yadkin. By 1768, the Cheraw numbered about 68 people.[3]

After 1716, the Keyauwee were located along the NC/SC border.[4]

All three of these tribes were either decimated or not located in the Upper Yadkin River Valley – or both – well before the Revolution. None of them threatened the Upper Yadkin River Valley at any time after John Burke was born, so we need to look for other possibilities among Native American tribes in North Carolina.

I found one: the only Native American tribe which continued to wage war into the 1790s, anywhere within range of the Upper Yadkin River Valley, were the Cherokee – especially the Cherokee who came to be called the Chickamaugua. Let’s talk about their history in some detail to get the big picture for you out-of-the-box thinkers, whose creativity I badly need.

The Cherokee and Chickamauga[5]

At the start of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the Cherokee joined the British and colonists in fighting the French. However, when some Cherokee were killed by Virginia settlers, they began attacking European settlements along the Yadkin and Dan Rivers. Although that is decades too early to play a part in the Moulders’ massacre story, it shows the Cherokee’s range beyond their hunting grounds in the mountains of western North Carolina.

In any event, the Cherokee attacks were short-lived. An army of British regulars, American militia, and Catawba and Chickasaw destroyed fifteen villages and defeated the Cherokee in June 1761. This ended Cherokee resistance, at least temporarily. The tribe signed a peace treaty in 1761 ending their war with the American colonists.

Two years later, King George III issued a proclamation purportedly defining the permissible western edge of European settlement. The so-called “1763 Proclamation Line” ran from north to south through western North Carolina at the eastern foot of the Appalachian mountains. European settlement was limited to the east of the line. To the west was the so-called Indian Reserve.

Despite King George (who did not, in the end, get much respect on these shores), western settlement proceeded. In the face of continued encroachment on their hunting grounds, the Cherokee announced their support for the Loyalists at the beginning of the Revolution and began waging war on the colonists. In July 1776, a force of 700 Cherokee attacked Eaton’s Station and Ft. Watauga, two U.S.-held forts now in east Tennessee that were then in North Carolina (which at the time extended west to include all of Tennessee). Both assaults failed, and the tribe retreated.

During the spring and summer of 1776, the Cherokees joined with a number of other tribes to raid frontier settlements in North and South Carolina, Georgia and Virginia in an effort to push settlers from their lands. The response to these raids was immediate and brutal. A large force of South Carolina militia and Continental Army troops attacked the Indians in South Carolina, destroying most of their towns east of the mountains. They then joined with North Carolina militia to do the same in NC and Georgia. Captured warriors were sold into slavery.

By 1777, Cherokee crops and villages had been destroyed and their power was broken. The badly defeated tribes could obtain peace only by surrendering vast tracts of territory in North and South Carolina at the Treaty of DeWitt’s Corner (May 20, 1777) and the Treaty of Long Island of Holston (July 20, 1777).[6] Peace reigned on the frontier for the next two years.

Cherokee raids flared up again in 1780. Punitive action by North Carolina militia (led inter alia by Col. John Sevier, the first governor of the short-lived state of Franklin and 6-term governor of Tennessee) soon brought the tribe to terms again. At the second Treaty of Long Island of Holston (July 26, 1781), previous land cessions were confirmed and additional territory ceded. The terms of the 1781 treaty were adhered to by all but the Chickamauga branch of the Cherokee. Here, apparently, were the only Native Americans who may have been involved in the Moulders’ massacre story in the 1790s.

The Chickamauga story began in 1775, when a land speculator named Richard Henderson convinced a group of Cherokee leaders to sell the tribe’s claim to twenty million acres, an area that included a large part of Kentucky and Middle Tennessee (a deal called “Henderson’s Purchase”). The area was an important hunting ground for the Cherokee and other tribes. For perspective, that is slightly more acreage than contained in the entire state of Sorth Carolina (19.2 million acres).[7] It encompassed that part of Middle Tennessee north of the Cumberland River and south of the Kentucky border – including Jackson County, where John Burke first appeared as a grown man in 1811.

One powerful Cherokee chief named Dragging Canoe and his followers strongly objected to the sale. Under the Cherokee system of government, anyone who disagreed with cessions of tribal territory was not expected to abide by the terms of the deal. Soon thereafter, Dragging Canoe’s towns, originally located in East Tennessee, moved futher southwest due to military raids. In 1779, they settled on Chickamauga Creek: thus their name. Their location was near present-day Chattanooga, on the Tennessee River at the Georgia/Tennessee border and about 40-50 miles west of the western tip of North Carolina.

An early attempt to settle the Middle Tennessee area of Henderson’s Purchase occurred in late 1779. It ran headlong into the Chickamauga. A group of men led by James Robertson went overland from East Tennessee to French Lick (i.e., Nashville), which is on the Cumberland River. Another group led by a John Donelson – made up largely of the families of the men in the Robertson group – went by boat down the Tennessee River heading for the Cumberland River, planning to go upstream on the Cumberland to join Robertson. Donelson’s party came under heavy fire from Chickamauga towns on the Tennessee River. One boat was captured along with 28 people on board, although most of the settlers eventually reached their destination at French Lick in the spring of 1780.

That, of course, took place before John Burke was born in the 1780s (or 1783, according to the Moulders). However, for the next fourteen years – 1780 through 1794 – the Chickamauga and their Creek allies continued attacks on Cumberland River settlements. Chief Dragging Canoe died in 1792, but his followers continued to fight against the Cumberland settlers for two more years.[8] Hostilities finally ended with the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in 1794, ending the long so-called “Cherokee Wars.” Peace followed.

Peaceful Cherokee remnants stayed in the eastern TN/western NC area until the 1830s, when the U.S. government forced most of them to move to Oklahoma. You may know this relocation as the “Trail of Tears,” when 17,000 Cherokee were removed by federal troops and marched to Oklahoma. A quarter of them didn’t survive the journey. Where and when I went to school, history books didn’t mention either the Trail of Tears or the Jim Crow lynchings of black men, women and children. The victors — white, in this instance — wrote the history books.

Summary, of sorts

At this point, I can think of only limited alternatives for interpreting the Moulders’ massacre story:

- Take it at face value, and assume a renegade batch of still-hostile Native Americans killed some settlers (including some Burkes) in, perhaps, Surry or Wilkes Co., NC in 1797-ish. This flies in the face of the history that I have read. I readily acknowledge that the information I have seen is only about an inch deep.

- Toss out the entire story as a tall tale. This flies in the face of the fact that oral family histories/legends almost always contain some element of truth. I have a hard time discarding the legend altogether, although it is quite possible that John Burke was a teller of tall tales. More on that later.

- Imagine an alternative story in which some Burkes were killed some time other than the late 1790s in the Upper Yadkin River Valley.

Somebody please come up with a viable idea …

And that’s all I can do with the Moulders’ massacre story. Next up: John Burke’s children by his wives Elizabeth Graves and Jane D. Basham.

[1] I give John Burke’s year of birth as “about 1785,” because the 1820 and 1830 census records (both showing that he was born during 1780-1790) are the only evidence of his date of birth in any official records.

[2] Historically, the Indians who came to be called “Catawba” occupied the Catawba River Valley above and below the present-day North Carolina-South Carolina border in the southern part of the Piedmont. Disease, especially smallpox, decimated the tribe. The tribe abandoned their towns near Charlotte, NC and established a unified town at Twelve Mile Creek in what was then South Carolina but is now Union County, NC, southeast of Charlotte. They also negotiated a land deal with South Carolina that established a reservation 15 miles square. By the time of the American Revolution, the Catawba were surrounded by and living among the Europeans settlers, who did not consider them a threat. In September 1775, the Catawba pledged their allegiance to the colonies, and fought against the Cherokee and against Cornwallis in North Carolina. Upon their return in 1781, they found their village destroyed and plundered. By the end of the eighteenth century, it appeared to most observers that the Catawba people would soon be extinct. By 1826, only 30 families lived on the reservation. See http://www.ncpedia.org/catawba-indians, http://catawbaindian.net/about-us/early-history/ and http://www.encyclopedia.com/history/united-states-and-canada/north-american-indigenous-peoples/catawba.

[3] Around 1700, the Cheraw were located near the Dan River on the NC/VA line. About 1710, they moved southeast and joined the Keyauwee (see the next footnote). Between 1726 and 1729, they joined with the Catawba (see the prior footnote). Although the Cheraw were noted later for their persistent hostility to the English, they were not in locations in the Yadkin River Valley. By 1768, surviving Cheraw numbered 68 people. See

http://www.carolana.com/Carolina/Native_Americans/native_americans_cheraw.html, http://www.sciway.net/hist/indians/cheraw.html, and http://www.ncpedia.org/saura-indians.

[4] Around 1700, the Keyauwee lived around the junction of Guilford, Davidson, and Randolph Counties in north-central North Carolina near the city of High Point – a bit east of the Yadkin River Valley. They ultimately settled on the Pee Dee River (i.e., the Yadkin after it flows into SC) after 1716 and probably united with the Catawba. In a 1761 atlas, their town appears close to the boundary line between the two Carolinas. They were no threat to the Upper Yadkin River Valley.

http://www.carolana.com/Carolina/Native_Americans/native_americans_keyaunee.html

[5] https://www.britannica.com/event/Cherokee-wars-and-treaties. I read several other sources on the web, trying to seek out scholarly articles. I did waaaay too many clicks for me to record in an orderly fashion, but the one source to which I’ve linked here is a good one.

[6] http://teachingushistory.org/lessons/treatyofdewittscorner.htm

[7] http://www.statemaster.com/graph/geo_lan_acr_tot-geography-land-acreage-total

[8] http://www.nativehistoryassociation.org/dragging_canoe.php