I need help with John Burke. The problem with John calls for the ability to look at facts in creative ways and do some outside-the-box critical thinking. I’m more of a two-plus-two-equals-four kind of person, and my linear logic is not working well. I hope anyone with ideas will leave a comment. The issue is what to make of a family legend saying that John Burke’s older brother and his family, with whom John was migrating, were killed by Native Americans. It matters because it is part of a larger issue: where was John Burke’s family of origin, and when?

The massacre legend comes from the second of two written family histories about John Burke. I posted an article on 8/11/17 about the first history, a document written by John Burke’s great-grandson Victor Moulder — Part 1 of this series. The second history is titled “Burke Family in Tennesse [sic] and Kentucky by Victor and Geo. B. Moulder 1946.” George and Victor were brothers who had a good bit to say, most of which I will defer for a later article.

The massacre story – if taken literally with respect to time and place – is not consistent with historical facts. Of course, every genealogist who has dealt with oral family history legends knows that they are rarely 100% factually correct. Nevertheless, they virtually always contain an element of truth, or at least point toward some truth. So far, I have been unable to figure out the “true facts” to which the massacre story points.

Here is the relevant part of the Moulders’ story:

“John Burke … migrated [from Virginia] at the age of 14 to the Upper Yadkin River Country, North Carolina with an older brother and family who were killed by Indians … joined a company of immigrants to Tennessee, walked and worked his way as a cobbler.”

To place the timing of the story, the Moulders say John Burke was born in 1783. That date is consistent with the 1820 and 1830 censuses, which show John as having been born during 1780 to 1790.[1] A birth date in 1783 would put the date of the Burke family migration at 1797. Glossing over the precise dates, the gist of the story is that a teenage John Burke’s older brother and his family were killed by Native Americans in the late 1790s in the Upper Yadkin River Valley.

Either the date, the location, or both must be incorrect, because there weren’t any hostilities between Native Americans and European settlers in the Upper Yadkin River Valley in the 1790s. At least I haven’t been able to find any.

At this point, we need briefly to address some geography and Native American history. This is emphatically not a scholarly treatment by any stretch of the imagination, so please alert me to anything that doesn’t jibe with what you know.

First, location: the Upper Yadkin River Valley

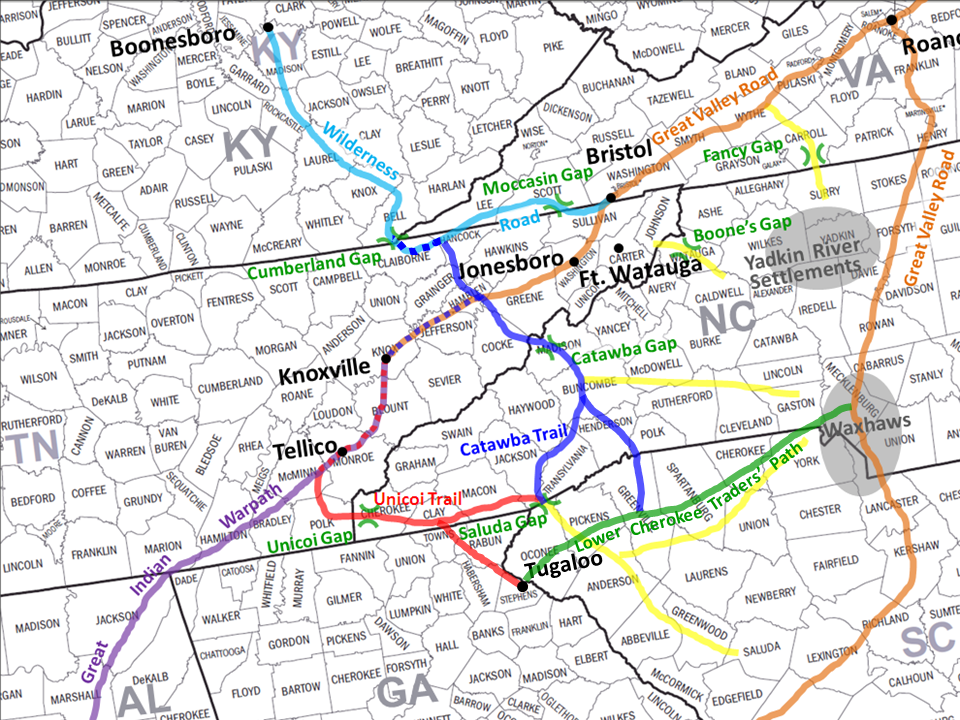

The Yadkin River roughly bisects North Carolina, flowing generally from north to south into South Carolina, where it becomes the Pee Dee River. Here is a map of some colonial migration routes in North Carolina which highlights in the upper gray circle the “Yadkin River Settlements.”

The area includes parts of current NC counties of Wilkes, Surry, Yadkin, Forsyth, Davie, Iredell and a sliver of Alexander. As of 1790 (before several of those counties were created), the relevant counties would have been Wilkes, Surry, Iredell and Rowan.

Native American players

Google was unable to answer my simple-minded question, “what hostile Native American tribes lived in the Upper Yadkin River Valley in the late 1700s?” Deprived of an easy answer, I started at the very beginning, with a map of Native American tribe locations in North Carolina before European settlers appeared.

The map shows three tribes whose range probably included part of the upper Yadkin River valley, although not necessarily during the 1790s: the Catawba, Cheraw, and Keyauwee. The map also shows the Cherokee in western NC in the area of the Blue Ridge Mountains, just a bit west of the Yadkin River Valley.

None of those first three tribes threatened settlers in the Upper Yadkin Valley in the late 1700s, so far as I have been able to find.

The Catawba, who were friendly to European settlers, lived prior to the Revolution in the Catabaw River Valley around Charlotte, NC and into South Carolina. They were virtually extinct by the end of the 18th century, decimated in large part by smallpox.[2]

By the 1720s, the Cheraw (or Saura) were located on the upper Pee Dee near the NC/SC border, well south of the Upper Yadkin. By 1768, the Cheraw numbered about 68 people.[3]

After 1716, the Keyauwee were located along the NC/SC border.[4]

All three of these tribes were either decimated or not located in the Upper Yadkin River Valley – or both – well before the Revolution. None of them threatened the Upper Yadkin River Valley at any time after John Burke was born, so we need to look for other possibilities among Native American tribes in North Carolina.

I found one: the only Native American tribe which continued to wage war into the 1790s, anywhere within range of the Upper Yadkin River Valley, were the Cherokee – especially the Cherokee who came to be called the Chickamaugua. Let’s talk about their history in some detail to get the big picture for you out-of-the-box thinkers, whose creativity I badly need.

The Cherokee and Chickamauga[5]

At the start of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the Cherokee joined the British and colonists in fighting the French. However, when some Cherokee were killed by Virginia settlers, they began attacking European settlements along the Yadkin and Dan Rivers. Although that is decades too early to play a part in the Moulders’ massacre story, it shows the Cherokee’s range beyond their hunting grounds in the mountains of western North Carolina.

In any event, the Cherokee attacks were short-lived. An army of British regulars, American militia, and Catawba and Chickasaw destroyed fifteen villages and defeated the Cherokee in June 1761. This ended Cherokee resistance, at least temporarily. The tribe signed a peace treaty in 1761 ending their war with the American colonists.

Two years later, King George III issued a proclamation purportedly defining the permissible western edge of European settlement. The so-called “1763 Proclamation Line” ran from north to south through western North Carolina at the eastern foot of the Appalachian mountains. European settlement was limited to the east of the line. To the west was the so-called Indian Reserve.

Despite King George (who did not, in the end, get much respect on these shores), western settlement proceeded. In the face of continued encroachment on their hunting grounds, the Cherokee announced their support for the Loyalists at the beginning of the Revolution and began waging war on the colonists. In July 1776, a force of 700 Cherokee attacked Eaton’s Station and Ft. Watauga, two U.S.-held forts now in east Tennessee that were then in North Carolina (which at the time extended west to include all of Tennessee). Both assaults failed, and the tribe retreated.

During the spring and summer of 1776, the Cherokees joined with a number of other tribes to raid frontier settlements in North and South Carolina, Georgia and Virginia in an effort to push settlers from their lands. The response to these raids was immediate and brutal. A large force of South Carolina militia and Continental Army troops attacked the Indians in South Carolina, destroying most of their towns east of the mountains. They then joined with North Carolina militia to do the same in NC and Georgia. Captured warriors were sold into slavery.

By 1777, Cherokee crops and villages had been destroyed and their power was broken. The badly defeated tribes could obtain peace only by surrendering vast tracts of territory in North and South Carolina at the Treaty of DeWitt’s Corner (May 20, 1777) and the Treaty of Long Island of Holston (July 20, 1777).[6] Peace reigned on the frontier for the next two years.

Cherokee raids flared up again in 1780. Punitive action by North Carolina militia (led inter alia by Col. John Sevier, the first governor of the short-lived state of Franklin and 6-term governor of Tennessee) soon brought the tribe to terms again. At the second Treaty of Long Island of Holston (July 26, 1781), previous land cessions were confirmed and additional territory ceded. The terms of the 1781 treaty were adhered to by all but the Chickamauga branch of the Cherokee. Here, apparently, were the only Native Americans who may have been involved in the Moulders’ massacre story in the 1790s.

The Chickamauga story began in 1775, when a land speculator named Richard Henderson convinced a group of Cherokee leaders to sell the tribe’s claim to twenty million acres, an area that included a large part of Kentucky and Middle Tennessee (a deal called “Henderson’s Purchase”). The area was an important hunting ground for the Cherokee and other tribes. For perspective, that is slightly more acreage than contained in the entire state of Sorth Carolina (19.2 million acres).[7] It encompassed that part of Middle Tennessee north of the Cumberland River and south of the Kentucky border – including Jackson County, where John Burke first appeared as a grown man in 1811.

One powerful Cherokee chief named Dragging Canoe and his followers strongly objected to the sale. Under the Cherokee system of government, anyone who disagreed with cessions of tribal territory was not expected to abide by the terms of the deal. Soon thereafter, Dragging Canoe’s towns, originally located in East Tennessee, moved futher southwest due to military raids. In 1779, they settled on Chickamauga Creek: thus their name. Their location was near present-day Chattanooga, on the Tennessee River at the Georgia/Tennessee border and about 40-50 miles west of the western tip of North Carolina.

An early attempt to settle the Middle Tennessee area of Henderson’s Purchase occurred in late 1779. It ran headlong into the Chickamauga. A group of men led by James Robertson went overland from East Tennessee to French Lick (i.e., Nashville), which is on the Cumberland River. Another group led by a John Donelson – made up largely of the families of the men in the Robertson group – went by boat down the Tennessee River heading for the Cumberland River, planning to go upstream on the Cumberland to join Robertson. Donelson’s party came under heavy fire from Chickamauga towns on the Tennessee River. One boat was captured along with 28 people on board, although most of the settlers eventually reached their destination at French Lick in the spring of 1780.

That, of course, took place before John Burke was born in the 1780s (or 1783, according to the Moulders). However, for the next fourteen years – 1780 through 1794 – the Chickamauga and their Creek allies continued attacks on Cumberland River settlements. Chief Dragging Canoe died in 1792, but his followers continued to fight against the Cumberland settlers for two more years.[8] Hostilities finally ended with the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in 1794, ending the long so-called “Cherokee Wars.” Peace followed.

Peaceful Cherokee remnants stayed in the eastern TN/western NC area until the 1830s, when the U.S. government forced most of them to move to Oklahoma. You may know this relocation as the “Trail of Tears,” when 17,000 Cherokee were removed by federal troops and marched to Oklahoma. A quarter of them didn’t survive the journey. Where and when I went to school, history books didn’t mention either the Trail of Tears or the Jim Crow lynchings of black men, women and children. The victors — white, in this instance — wrote the history books.

Summary, of sorts

At this point, I can think of only limited alternatives for interpreting the Moulders’ massacre story:

- Take it at face value, and assume a renegade batch of still-hostile Native Americans killed some settlers (including some Burkes) in, perhaps, Surry or Wilkes Co., NC in 1797-ish. This flies in the face of the history that I have read. I readily acknowledge that the information I have seen is only about an inch deep.

- Toss out the entire story as a tall tale. This flies in the face of the fact that oral family histories/legends almost always contain some element of truth. I have a hard time discarding the legend altogether, although it is quite possible that John Burke was a teller of tall tales. More on that later.

- Imagine an alternative story in which some Burkes were killed some time other than the late 1790s in the Upper Yadkin River Valley.

Somebody please come up with a viable idea …

And that’s all I can do with the Moulders’ massacre story. Next up: John Burke’s children by his wives Elizabeth Graves and Jane D. Basham.

[1] I give John Burke’s year of birth as “about 1785,” because the 1820 and 1830 census records (both showing that he was born during 1780-1790) are the only evidence of his date of birth in any official records.

[2] Historically, the Indians who came to be called “Catawba” occupied the Catawba River Valley above and below the present-day North Carolina-South Carolina border in the southern part of the Piedmont. Disease, especially smallpox, decimated the tribe. The tribe abandoned their towns near Charlotte, NC and established a unified town at Twelve Mile Creek in what was then South Carolina but is now Union County, NC, southeast of Charlotte. They also negotiated a land deal with South Carolina that established a reservation 15 miles square. By the time of the American Revolution, the Catawba were surrounded by and living among the Europeans settlers, who did not consider them a threat. In September 1775, the Catawba pledged their allegiance to the colonies, and fought against the Cherokee and against Cornwallis in North Carolina. Upon their return in 1781, they found their village destroyed and plundered. By the end of the eighteenth century, it appeared to most observers that the Catawba people would soon be extinct. By 1826, only 30 families lived on the reservation. See http://www.ncpedia.org/catawba-indians, http://catawbaindian.net/about-us/early-history/ and http://www.encyclopedia.com/history/united-states-and-canada/north-american-indigenous-peoples/catawba.

[3] Around 1700, the Cheraw were located near the Dan River on the NC/VA line. About 1710, they moved southeast and joined the Keyauwee (see the next footnote). Between 1726 and 1729, they joined with the Catawba (see the prior footnote). Although the Cheraw were noted later for their persistent hostility to the English, they were not in locations in the Yadkin River Valley. By 1768, surviving Cheraw numbered 68 people. See

http://www.carolana.com/Carolina/Native_Americans/native_americans_cheraw.html, http://www.sciway.net/hist/indians/cheraw.html, and http://www.ncpedia.org/saura-indians.

[4] Around 1700, the Keyauwee lived around the junction of Guilford, Davidson, and Randolph Counties in north-central North Carolina near the city of High Point – a bit east of the Yadkin River Valley. They ultimately settled on the Pee Dee River (i.e., the Yadkin after it flows into SC) after 1716 and probably united with the Catawba. In a 1761 atlas, their town appears close to the boundary line between the two Carolinas. They were no threat to the Upper Yadkin River Valley.

http://www.carolana.com/Carolina/Native_Americans/native_americans_keyaunee.html

[5] https://www.britannica.com/event/Cherokee-wars-and-treaties. I read several other sources on the web, trying to seek out scholarly articles. I did waaaay too many clicks for me to record in an orderly fashion, but the one source to which I’ve linked here is a good one.

[6] http://teachingushistory.org/lessons/treatyofdewittscorner.htm

[7] http://www.statemaster.com/graph/geo_lan_acr_tot-geography-land-acreage-total

[8] http://www.nativehistoryassociation.org/dragging_canoe.php

When I hear “moved to the Upper Yadkin,” I think right away of Surry Co., North Carolina, Robin. In the period before the Revolution and then during the Revolution, there was quite a bit of movement of families out of southwest Virginia into Surry Co., North Carolina. The movement was often back-forth movement, so that folks can be found a while in Surry and then back in counties like Wythe Co., Virginia. Eventually, many of those families moved on into Tennessee following the war.

At least one reason families were migrating to Surry from southwestern Virginia in that period is that there were definitely Cherokee depradations going on in southwestern Virginia — this is at an earlier period, of course, than when the family stories have your John Burke and his brother moving to the Upper Yadkin. And people were moving inland and down to North Carolina hoping to escape those depradations.

Supposedly, my ancestor Ezekiel Calhoun was shot by a native American while Ezekiel stood in the doorway of his cabin in Wythe County in the spring of 1762. He had gone back from Abbeville Co., South Carolina, where the family had moved in 1758 to check on his land in Wythe County. I have never been entirely convinced that the person who shot Ezekiel was a native American, however. The Calhouns feuded bitterly with the Pattons in Wythe County during the period in which the Calhouns lived there, and I think it’s very possible someone else shot Ezekiel.

There was, though, as you know, I’m sure, a lot of concern along the western borders of Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas in the period leading up to the Revolution and during the Revolution about hostilities from the Cherokees, and one reason the animosity between families that took different sides was so strong in the western Carolina region during the Revolution is that families who had lost members due to these hostilities thought their Loyalist neighbors had exposed them to hostile attacks by the Cherokees.

As you probably know, when the Calhouns moved down out of southwest Virginia into the South Carolina upcountry, then got caught in the middle of these hostilities and a number of family members, including the family matriarch Catherine Montgomery Calhoun, were killed by the Cherokees in the Long Cane massacre in 1760. All of this is one reason Revolutionary troops, many of them from the North Carolina piedmont area, marched into Cherokee territory during the war and burned Cherokee towns down.

What I’m winding around to: I wonder if the memory of a Burke family member killed by native folks when John Burke and his older brother came to the Upper Yadkin really points to an incident prior to their move to the Yadkin, which may even have been part of why John moved to North Carolina? Have you checked Chalkley’s Chronicles to see if he mentions Burkes/Burks/Birks/(Burches?) in old Augusta Co., Virginia, from which the counties in southwestern Virginia that fed into the migration to Surry Co., North Carolina, were formed? Just a thought.

I would also be inclined to search Surry Co., North Carolina, records and see what I find. I do spot (using Ancestry’s search engine for NC estate files) a number of Burke estates in Surry going back into the 1770s. I have perused these to see if I might spot some useful information that could help you with this search.

I realize these are needle-in-a-haystack suggestions, and you may well find a welter of people in Chalkley and in Surry Co., North Carolina, records named John or James Burke. You’d then have the problem of figuring out if any of them connect to your family. On the other hand, it’s possible you’d find a reference to some document mentioning the killing of a Burke man by native Americans. Chalkley’s book is, as you probably know, sort of an index to many records of old Augusta Co., Virginia, pointing you back to the original documents, which are often very rich in genealogical material not included at all in Chalkley’s book — especially court case files.

I hope these are not just wild thoughts leading nowhere at all. They’re what pops into my head when I read about the conundrum with which you’re working.

Those are (of course!) helpful thoughts, Bill. The notion that some members of the Burke family may have been killed in VA rather than NC has some appeal. The PROBLEM is that any killing of Burkes — either in VA or in the Yadkin — MUST have been before John Burke was born. For a variety of reasons, including the timing of the long Cherokee wars, I don’t believe the timing of the legend. Among other things, John Burke had 6 enslaved people in the 1840 census and owned more than 500 acres on the Cumberland River. NOT, one would think, a former orphan whose family was killed while migrating and who then walked to TN working as a cobbler.

The other problem (and I haven’t discussed this in a post yet) is that John Burke was reportedly born, according to the Moulders’ legend, in a county on the James River in Tidewater Virginia. The Burkes there weren’t among those who came down the Shenandoah Valley to old Augusta County from Lancaster Co., PA and environs. The James River crowd were Brits.

Also, the Surry County Burkes are fairly well-documented. They are DEFINITELY from the Augusta crowd, and didn’t ever (so far as I have found) live in the James/Tidewater area. I suspect a connection with them, but will have to figure out how to reconcile the James/Tidewater part of the legend with any connection to the Surry County Burkes. The best option is that there was a SECOND Burke family there! Hahahaha … John Burke has been a brick wall for 20 years. ANY progress would be amazing!

Thanks for taking the time to write.

RRW

For the reasons you state, the story of the killing of John’s brother on the Upper Yadkin after the two brothers came there sounds implausible to me, too. I find with these family stories of massacres of settlers by native Americans often get discombobulated, detached from their proper historical circumstances.

In my Brazelton/Braselton family, one of the grandsons of the immigrant ancestor is said — longstanding family tradition — to have been killed by Indians on Bear Grass Creek in Kentucky in 1788. There actually was an attack on settlers in Kentucky on that creek in that year, but those who were killed in it included members of the Westerfield/Westervelt family into which this Brazelton man married, and not a Brazelton. Somehow, a story connected to a family married into the Brazelton line has gotten picked up by the Brazeltons as a family story about their own family.

Yes, I had wondered about the James River place of origin for your Burkes, too, as I thought about the possibility that they were in southwest Virginia and then in Surry Co., North Carolina. Does John’s Graves spouse tie them to the James River part of Virginia? If so, then that story could well be true.

There was, though, a migration pattern down to southwest Virginia from the tidewater and piedmont counties of Virginia in the mid-1700s. I actually once heard Mary B. Kegley, the noted expert on Wythe County history and the history of surrounding counties, give a lecture on that very topic at Wytheville. One of my families that sojourned in Wythe County and then went on to Kentucky in the early 1800s was a Whitlock family that came to Wythe from Louisa County, Virginia, with roots in New Kent County prior to that.

Part of what seems to have drawn some tidewater and piedmont folks to that part of Virginia was the mining operation that John Chiswell, who himself had tidewater Virginia roots, set up in Wythe County. No records I’ve ever found indicate to me that the Whitlocks had any connection to that mining business, though one of the sons of the Whitlock forebear who made the trek from Louisa to Wythe County married a Davies woman whose family did have a connection to Chiswell’s mining operation. Chiswell also operated a store in Louisa, I think, and this may have accounted for some of the movement from Louisa to Wythe.

The Whitlocks are a family that I’ve found appear in Wythe records, then in Surry records, and then back in Wythe — a branch of the Wythe County family made that migration in the late 1700s and early 1800s, I find. Lots of Surry settlers arrived there via the valley of Virginia, but some also came down directly from the Virginia piedmont and had tidewater roots.