This article continues an apparently never-ending series on John Burke, born in Virginia in about 1785 and died in 1842 in Jackson County, Tennessee. This Part Three contains information from two very dissimilar sources: (1) two family histories written by grandchildren of John Burke and (2) newspaper and court records. As to the histories, John’s great-grandson Victor Moulder wrote one of them. Victor and his brother George B. Moulder collaborated on the second. Images and information from both are ubiquitous on Ancestry.com. Unfortunately, some of the information about John Burke’s children from the histories is wrong, particularly regarding their migration history.

I do not mean to denigrate the Moulders’ histories, for which I am grateful. The brothers probably had no information other than oral family history handed down for three generations – over a century. I don’t know about you, but I can rarely tell the same story exactly the same every time. Inaccuracies due to the distance of time and fading memory creep in, and occasional, um, embellishments are introduced to keep the conversation lively. Some of the Moulders’ information was probably incorrect two generations before they wrote it down, and the oral tradition guarantees that new errors were introduced over time. Obviously, the Moulders didn’t have easy access to census records, court filings and tombstones to supplement their information. Fortunately, we do.

With that in mind, let’s begin with some more information from the Moulders before we get on to the other sources. This deals with “lite” facts and easily-resolved issues. If you need to get up to speed, here are links to Part One and Part Two of the John Burke series. And here is some of what the Moulders’ history said about their great-grandfather:

John Burke was born … in 1783 (died 1853) … took up a claim on War Trace Creek at Cumberland River near Gainesboro, Jackson Co. Tenn.; married Elizabeth Graves, who was born 1786 of Irish extraction (died 1831) … second wife [was] Janie Lamb.

John Burke’s dates of birth and death. As noted in Part Two, a birth year of 1783 is consistent with John’s age ranges according to the 1820 and 1830 federal censuses. He died on June 6, 1842, not 1853, according to his widow and several court filings reciting the month and year. John’s widow appeared in the 1850 census for Jackson Co. as Jane D. Byrk. Her household included her five children by John Burke and a sixth child named Burke who was too young to have been fathered by John.[1]

John Burke’s wives. Yes, John Burke’s first wife was Elizabeth Graves, daughter of Esom Graves and Judith Parrott. Elizabeth could have been born in 1786 since the 1820 census shows her as having been born during 1775–94. An 1831 date of death for her is wrong, because there is no female the right age to be Elizabeth in the 1830 census. Her last child was born in 1828.

Whether Elizabeth was “of Irish extraction” may be unprovable. I haven’t been able to prove her paternal line any earlier than her grandfather, John Graves. He was born in Virginia about 1735 (a rough guess based on his eldest son’s age) and lived in at least Spotsylvania and Halifax counties, Virginia.[2] Many, if not most, of the Graves found in colonial Virginia were descended from Capt. Thomas Graves, who arrived in Virginia in the early 1600s. Y-DNA tests prove that Elizabeth’s line wasn’t descended from Thomas Graves, but don’t (so far as I know) provide evidence of her Graves line’s country of origin. Elizabeth’s maternal line, the Parrotts, had been in the colonies since the 1650s, and they were from England.

John Burke’s second wife was Jane D. Basham, not Lamb, as she herself stated on her widow’s application for pension for John Burke’s War of 1812 service. That was almost certainly her maiden name.

The identity of John Burke’s children.

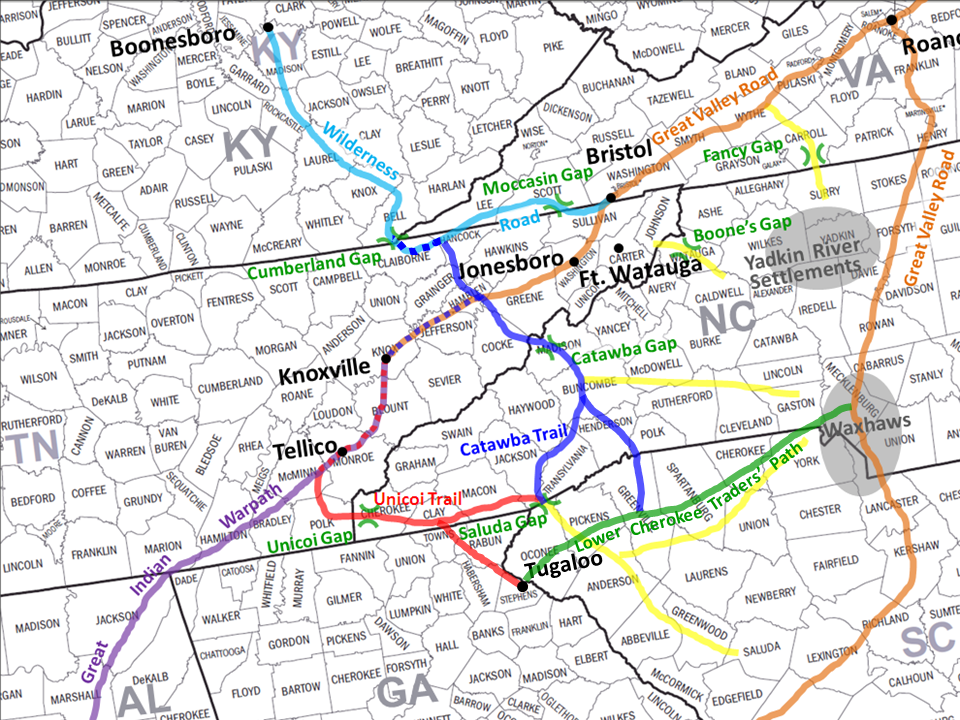

Let’s switch gears in terms of source material. No more “facts lite,” we are now into dense legal language. There are two documents which conclusively establish the identities of John Burke’s children: a newspaper ad[3] and a chancery court complaint.[4] They are a veritable genealogical gold mine. One of them even names a number of grandchildren (including my great-grandfather William Logan Burke, an early sheriff of McClennan Co., TX) and states the locations of many of John’s heirs. Let’s look closely at each document.

The Newspaper Ad. The first document concerns Jane D. Basham Burke’s application to a Jackson County court for a “writ of dower” to allot her dower portion of John Burke’s land. The law required her to give notice of her petition to John’s heirs. Requisite notice could be accomplished by taking out an ad or ads in local newspapers.[5] The notice, dated August 19, 1842, was published in the September 8, 1842 issue of The Republican, a local newspaper, and apparently reprinted in The Smith County Democrat.[6] It has the benefit of being contemporaneous evidence, which is inheritantly more reliable and persuasive than evidence provided at a later date. Furthermore, two very good witnesses – John’s widow Jane and his son John Carroll Burke, one of the estate administrators – undoubtedly provided the names of the heirs for the notice. The notice names only fifteen children. Jane was pregnant at the time with their daughter Matilda, who was born after the date of the notice.

Here is an image of the Newspaper Ad.

Note that John Burke’s two sons-in-law are identified in the notice. Until the twentieth century, a married woman in most states had no legal existence apart from her husband. Thus, a son-in-law, rather than a daughter, was actually the party to any lawsuit and was the designated recipient of any notice. Fortunately, the notice also names John’s married daughters. Note also that the children are not named in birth order: the last two were sons of Elizabeth Graves Burke.

Here is a transcription of the first paragraph of the article, with some additions. I have numbered John Burke’s children, added punctuation and spacing for clarity, and included some annotations in italics:

To

(1) Henry F. Burke,

(2) William G. Darwin and his wife Polly (formerly Polly Burke, a nickname for Mary),

(3) Alva Graves and his wife Parmelia (formely Parmelia Burke),

(4) James Burke (this is James W. Burke),

(5) John Burke (John G. Burke),

(6) William C. Burke (middle name Carroll),

(7) Elizabeth Burke and

(8) Paresiba (usually spelled ParesiDa) Burke by their guardian William G. Darwin (Darwin was the guardian of Elizabeth and Paresida, the only two in the preceding list who were still minors),

(9) Esom L. Burke (middle name Logan),

(10) Elvira Burke,

(11) James F. Burke (sic, this should be Jonas Burke),

(12) America O. Burke,

(13) Milly Jane Burke,

(14) Francis M. Burke (middle name Marion), and

(15) Franklin P. Burke (middle name Parrott),

by their guardian pendente lite, Richard P. Brooks (the guardian of children 9 through 15, all still minors in 1842), heirs of John Burke, deceased, and [notice is also given to] Richard P. Brooks and Carrol C. Burke (sic, William Carroll Burke), administrators of said John Burke, dec’d.

And that’s all the news that’s fit to print from the Newspaper Ad.

The Chancery Court Complaint

The second piece of fabulous evidence is an original complaint filed in the Jackson County chancery court in 1884 concerning John Burke’s estate. Briefly, some of John’s heirs alleged that Richard P. Brooks, one of the administrators of the estate, defrauded them regarding John’s land. I have no idea how the suit turned out, although there might be records to be found among the Jackson County microfilm. That film is a tough slog.

Like the application for dower allotment, all of John Burke’s heirs had to be named as parties to the lawsuit — because all had an interest in the estate. If one of John’s children had died by that time (in fact, several had died by 1884), then their children were heirs to the estate and had to be named. For this, we can be grateful that John Burke died without a will.

The list of heirs in the Chancery Complaint was obviously not contemporaneous with John Burke’s death in 1842. Because it is forty years later, it is obviously less reliable than the newspaper notice. The Complaint contains errors and omissions, as well as “blanks” where the complainants didn’t know the facts. Most of the “holes” can be filled with other evidence, though. Just the locations are worth their weight in gold for tracking this family.

Here is the Chancery Court Complaint’s list of John Burke’s children: Henry F. Burke, John G. Burke, Polly Burke, Permelia Burke, William C. Burke, James W. Burke, Esom L. Burke, Francis M. Burke, Parazidia Burke, Franklin P. Burke, Elisabeth Burke, Elvira Burke, America Burke, Matilda Burke, Jonas Burke, & Jane Burke, his only heirs at law. This list is closer to birth order than the other list, but still not quite accurate.

I am going to reproduce my transcription of the Chancery Court Complaint in its entirety, below. In the next article in this series, I will (finally!) take up information about the children themselves.

_________________

Transcription of the Original Complaint dated July 28, 1884 in the suit John G. Burke et al. vs. R. V. Brooks et al., Chancery Court of Jackson County, Tennessee. Transcribed from original document on TSLA Microfilm, Jackson Co., TN Roll No. 53, folder titled “Burke John G. & others vs Brooks R. V. & others, Chancery 1884.” Xerox copy made from FHL Film # 985,278.

“To William G. Crowley, Chancellor, holding the chancery Court at Gainsboro, Tennessee:

The Bill of Complaint of John G. Burke, Leonidas Darwin, William H. Darwin, Hiram C. Darwin, George C. Darwin, Mary A. Suite, Elizabeth Kelly & her husband Miles Kelly, Mary Carter & her husband William Carter, Milton E. Burke, John M. Burke, Sarah E. Hornbuckle & her husband [first name struck through] Hornbuckle, Angelina McCarry & her husband _______ McCarry, Elizabeth Padgett & her husband James Padgett, Ella Buhler & her husband Alexander Buhler, Adda Bettis & her husband William Bettis, Lucy Moore, Parazidia Lipscomb & her husband ______ Lipscomb, Permelia Lipscomb & her husband ______ Lipscomb, William L. Burke, John P. Burke, Franklin P. Burke, James P. Burke, Uhley Woollard & her husband Henry Woollard, Sally B. Burke, Francis M. Burke, Franklin P. Burke Sr., Elizabeth Simpson & her husband Thomas D. Simpson, W______ P. Hopkins, M_____ B. Hopkins, John O. Hopkins, M______ E. Hopkins & her husband Sydney Hopkins [additional interlining unreadable], Andrew L. Hopkins, Mary Ann Hopkins, Nannie B. Hopkins, John Anderson, Juda Anderson & her husband ____ Gibson?, Henry Burke, Jno R. Burke, Thomas Burke, Elizabeth Parker & Marion Burke, complainants

against

V. Brooks, personally, and as Executor of the last will of Richard P. Brooks, deceased, Caleb Roberts, Josiah Roberts, Meredith Brown, & Asa Denson,

of Jackson County, Tennessee,

and Matilda Long & her husband Lane (?) Long of the State of Kentucky,

Defts. [sic, Defendants]

Your complainants, aforesaid, complaining, state that they are heirs at law of John Burke who died intestate in Jackson County, Tennessee where he resided about the year 1842, leaving surviving him a widow named Jane Burke and the children whose names follow to wit:

Henry F., John G., Polly, Permelia, William C., James W., Esom L., Francis M., Parazidia, Franklin P., Elisabeth, Elvira, America, Matilda, Jonas & Jane Burke, his only heirs at law.

Richard P. Brooks was appointed and acted as administrator of his personal estate and he has lately died and deft R. V. Brooks is his Executor appointed less than two years & six months ago. There are no debts against the estate of said John Burke.

Said John Burke the common ancestor of complainants, at his death owned several valuable tracts of land lying in Jackson County, Tennessee, on one of which he resided at the time of his death, and about 200 acres of it, the homestead, was duly allotted and assigned by the Circuit Court of said County to his said widow as her dower, and a decree of said court duly entered to that effect, and she took possession of it as such and resided on it for a considerable time and until she conveyed it or transferred it in some way as such dower and estate for her life to said Richard P. Brooks who went into possession of and held it as such during her natural life, which terminated on the ____ of _______, 1881, less than seven years before the filing of this bill; and it has been less than seven years since the right of action of the heirs of John Burke dec’d accrued for said dower land.

Said dower tract lies on the Cumberland River on the south side of it and is bounded North by Cumberland River, East by the lands of Joshua Haile Jr., South by the lands of R. A. Cox & Hoover and West by __________________ and lies in White’s Bend of said river. The lines cannot now be given by complts but reference is to be had to the lines of said dower as laid off by the Court, the records of which were destroyed & burned up some years ago without the intention or knowledge of complts.

It is believed and so charged from belief that deft Brooks or if not he some of the other claimants under his testator the defts have a copy of the decree allotting the said dower. If so let them answer as to it & produce it & file it with their answer.

Complts further allege that some time after the death of John Burke their ancestor said Richard P. Brooks the admr procured some of the heirs to join him in filing a bill or petition in the Circuit Court of Jackson County against others of the heirs to procure a sale or partition of the lands of said John Burke not covered by the dower and under it they were sold in or about the year 1843, as now remembered, by the clerk & commissioners of said Court and they were purchased in by said Richard P. Brooks or at least part of them were bought by him, including that part of the home tract not covered by the dower. There was a large quantity of the lands & quite valuable.

At the same time of the sale of the other lands outside of the dower said Richard P. Brooks fraudulently procured a pretended sale of the remainder in the land covered by said dower allotted to the widow, and pretended to purchase it in himself at the grossly inadequate price of three hundred dollars, or thereabout, although there was no application in the bill or petition to the court for a sale of it and under the law the court had no jurisdiction to sell it – the widow being then living.

The Heirs were all then young and most of them, including several of complts & their ancestors, under 21 years of age, and all ignorant in matters of law and conveyancing etc, and all relied on and confided in said Brooks, the admr., who was a shrewd person, versed in such matters, and, afterward, if not then, a lawyer.

They objected at the time of the sale, in the presence & hearing of said Brooks & others there to the sale of the dower land, and contended that there was no application to sell it; but, Brooks fraudulently & wrongfully went on and had it sold & bought it in, over their objections, and, as they now believe, & so charge, for the purpose of cheating the heirs out of it; for, among other badges of fraud, he afterward admitted to friends, at times, that he had no title to it, and that it was really the rightful property of the said heirs.

He, soon after this sale, purchased of the widow her life estate in dower and took possession of it as such, and held it up to her death, & to his own death about two years past, acknowledging the rights of the heirs to the remainder.

Complts charge that during the time said R. P. Brooks so held and occupied said land, he committed and permitted great waste and injury to it, and to the injury & damage of the heirs, by permitting it to dilapidate, by bad cultivation and husbandry of himself & tenants, by taking down & removing the fences & houses, etc., from it to his other lands; by cutting down & removing & deadining (?) & destroying the valuable timbers of which there was much; by destroying and permitting to be destroyed & injured the valuable orchards, to the damage of the heirs to large amounts. He also took the rents & profits of said land to large amounts, after the death of the widow, to which the heirs were entitled. And the other defts R. V. Brooks, Caleb Roberts, Josiah Roberts, Meredith Brown & Asa Denson have continued all these wrongs since, to the damage of the heirs. But the amounts of the rents & damages for which each or any of them is liable cannot be stated or ascertained without an accounti[ng] thereof; it being a matter of complicated account, fit, & fit only, to be ascertained by a court of chancery, and not fit or considerable in a court [remainder of this page is missing. The complainants are just asserting that the case must be tried in the chancery court, that the county court of law doesn’t have jurisdiction.]

They all claim under the title of John Burke the common ancestor of complts whose title papers are supposed to be in possession of deft Brooks, or if they are not they are so unintentionally lost or mislaid or destroyed that complts cannot find them & that the registration of them is also so unintentionally destroyed.

Said R. V. Brooks, Caleb Roberts, Nathan Roberts, Josiah Roberts, Meredith Brown & Asa Denson are the present occupants of said land, and claim it wrongfully, and refuse to give it up or, surrender the possession of it to the heirs of said John Burke, dec’d, or pay the rents & damages; though the heirs have duly demanded the same of them, and said rents and damages, with the interest thereon, are due and unpaid to the heirs.

Your complainants are informed & believe, and, so, charge, that Richard P. Brooks did not pay any thing for the said remainder interest in the land covered by said dower; and, therefore, he is not entitled in any event to any reimbursement. Yet, if it turn out that any of the heirs did in fact get any part of its proceeds, they are, respectively, willing to refund it & do justice, upon the land being surrendered or decreed to be given up to them; and they have offered this to the present occupants. But they refuse, as aforesaid, to surrender & pay. So, complts must sue for their rights.

At the death of said John Burke the common ancestor of complts his said lands descended to his aforesaid children, then living, equally. After his death some of them died and some of them died leaving issue who inherit through them their portions of said lands, and they are as follows: Polly, a daughter of said John the common ancestor, married William Darwin, and died leaving children to wit: Leonidas Darwin of Texas, William H. Darwin of Arkansas, Hiram C. Darwin of Texas, George C. Darwin of Jackson County, Tennessee, Mary A. [might be Ann] a daughter who married a man by name of Suite, but he is dead and she is a widow & resides in Texas; Elizabeth, who married Miles Kelly, and they reside in Kansas; Granville Darwin who died leaving one daughter Mary who has married ___________________ Carter & they reside in Jackson County Tennessee; Parasidia, a daughter, who married Alexander Taylor, & they reside in Arkansas; and Polley, a daughter, who died without issue after her mother died and her share descended to her brothers and sisters the children of Polly Darwin, aforesaid, equally.

Henry F. Burke, a son of the common ancestor, died about Nov., 1845, leaving four children, to wit: Milton E. Burke, John M. Burke, Sarah E. a daughter who has married _____________ Hornbuckle, all of the state of Missouri, and Angelina a daughter who has married _____ McCary who resides in Kansas.

Parasidia, a daughter of the common ancestor, married W. W. More [sic, Moore] and afterward died intestate, leaving the following children, to wit: Elisabeth a daughter who has married James Padgett of Wilson County, Tennessee; Ella, a daughter who has married Alexander Buhler of Wilson County, Tennessee; Adda(?), a daughter, who has married William Bettis of Wilson County, Tennessee; & Lucy Moore, a daughter, of Wilson County Tennessee;

Permelia, a daughter of the common ancestor, married Alva Graves, and they are both dead, leaving two children, daughters, to wit, Parasidia, who married _____ Lipscomb, and Permelia, who married ____________ Lipscomb, all of the state of Missouri.

Esom L., a son of the common ancestor, died, leaving the following children, all of whom reside in Wilson County, Tennessee, to wit: William L., John P., Franklin P. & James R. Burke, sons, and two daughters, to wit Uhley, now wife of Henry Woolard and Sallie B. Burke, the said F. P., Sallie B., & Jas R. are minors without guardians and sue by their brother & next friend William L. Burke.

The following children of the common ancestor are living to wit John G. of Wilson County, Tenn., Francis M. of Texas, Franklin P. of Missouri, sons, & Elizabeth the wife of Thomas D. Simpson of Texas, and Matilda, the wife of Lone(?) Long, of Kentucky.

Elvira, a daughter of the common ancestor, married Otey Hopkins, and died, leaving the following children, her only heirs, to wit: W.____P., M_____ D., John O., M_______ E., Sydney, Andrew L., Nannie B. & Mary Ann Hopkins. Sidney Hopkins Andrew Hopkins Naney B. Hopkins & Mary Jane Hopkins (John Anderson & Frances) Anderson minors who sue by their next friend George C. Darwin. [Note: I have transcribed this paragraph exactly as it appears in the original, so far as I can tell. The draftsman was clearly getting tired.]

America, a daughter of the common ancestor, married _______________ Anderson, and died, leaving the following children surviving her, to wit: Judey & John Anderson, who reside in Jackson County, Tennessee.

James B. Burke [sic, should be James W. Burke], son of the common ancestor, who died, leaving the following children & heirs to wit: Jno R. Burke, Thos. Burke, Elizabeth Parker, widow of ___________ Parker, and Marion Burke, citizens of the state of Kentucky.

Wm. C. Burke, son of the common ancestor, who died, leaving one child & heir Henry Burke, a citizen of the state of Kentucky.

The common ancestor had one son named Jonas at his death and a daughter born in lawful time a few months after his death whose name was Jane, as now remembered, who both died intestate & without marriage or issue many years ago, before the death of the widow and their shares descended to the other surviving heirs of the common ancestor to wit those herein stated in the same proportions as the other parts of the estate descended to them from said common ancestor. One error about John Burke’s sixteen children: Milly Jane wasn’t the afterborn child, who was named in the Newspaper Ad. The afterborn child was Matilda Burke Long.

Your complts further state that the said land sued for is not susceptible of partition among the owners of it owing to the number of owners being so great, for want of timber & water and being bounded and hemmed by adjacent owners’ lands and by the natural obstructions so that roads & ways for ingress & egress could not be had to & from it by reason of all which & perhaps other good reasons the value would be much diminished so that it is not susceptible of such partition in kind without manifest injury to the owners and it would be manifestly to the interest & advantage of the owners that the land be sold and the proceeds partitioned among them.

Prayer. The premises being considered, your complts pray that this bill be filed in said court, on behalf of Complts and of said Matilda Long & her husband, if they shall choose to avail themselves of its benefits under the rules of law & practice; that the persons named in the caption as defendants be made such by proper process & orders of publication etc; that they be compelled to answer fully, not on oath; that they answer as to the said copy of the decree & other title papers aforesaid and file with their answers if they have them; that upon hearing decrees be entered declaring the rights & title of complts & Long & wife and setting up their title to be complete in & to said land and vesting the same in them according to their several rights and that they be put in possession thereof; that the defts in possession & claiming the lands be held liable for the rents, waste & damages of the lands with interest thereon; that deft R. V. Brooks as Executor of the will of said Richard P. Brooks, deceased, and the estate of said Richard P. Brooks be held liable also for the same; that all proper & necessary accounts thereof be taken and reports made and all proper & necessary decrees entered to declare & enforce the rights of said heirs or if complts have mistaken their relief that such other and further relief be granted them as may seem right & lawful.

As the rental is quite valuable and some of the defendants not solvent complts pray that a Receiver be appointed to rent out the lands and secure the rents pending the litigation and such orders made & proceedings had as may be necessary & proper.

Complts also pray that defts be injoined from committing further waste or damage to the lands.

This is the first application for an injunction in this matter.

A. Swope

A. Witt? or Mott? Solicitors for complts

State of Tennessee Personally appeared before

Jackson County me H. W. Winn? Clerk & Master of the

Court of said county G. C. Darwin Jr.? one of the complainants in the foregoing bill and made oath that the facts stated in said bill are true as stated according to his information & belief. And those allegations made from information he believes to be true & subscribed this affidavit? before me on the 28th day of July 1884.

Sworn to G. C. Darwin [signature]

Test M. W. Winns? Clerk

[1] 1850 federal census, Jackson Co., TN, Jane D. Byrk, sic, Burke, 35, with Jonas Burke, 13, Elvira L. Burke, 12, America Burke, 10, Milly Burke, 9, Matilda Burke, 8 and Margaret Burke, 1. Margaret was not a child of John Burke, who died in June 1842. Nor was she a grandchild of John Burke’s.

[2] Virgil D. White, Genealogical Abstracts of Revolutionary War Pension Files, Volume II (Waynesboro, TN: The National Historical Publishing Co., 1991), abstract of the pension application of Reuben Graves, who testified that he was mustered into VA militia between age 15 and 16 as a substitute for his father John Graves; soldier lived in Halifax County, Virginia at enlistment, and was born 23 May 1760 in Spotsylvania County, Virginia; in 1805 he moved to Wartrace Creek in Jackson County, TN and he applied there 2 October 1832, aged 72. See also Catherine Lindsay Knorr, Marriage Bonds & Ministers Returns of Halifax County, Virginia 1753-1800 (1957), 11 Jan 1787, Esom Graves and Judith Parrott were married by Rev. James Watkins; 27 Nov 1786, Reuben Graves m. Elizabeth Yarborough. See also Halifax Co., VA Plea Book No. 14, Aug. Term 1789 to July Term 1790, original viewed by the author at the Halifax courthouse, an April 1790 road order tithables included both Reuben Graves and Esom Graves and established that they lived in the same fairly limited area. Finally, see Smith County, TN Deed Book B: 295, deed dated 3 Jun 1805 from Rencher McDaniel of Wilson to Reuben Graves, 250 acres on the waters of War Trace Creek on the north side of the Cumberland River adjacent Easom Graves, deed witnessed by Easom Graves. Reuben and Easom/Esom were brothers.

[3] Issue of The Republican dated Thursday, Sept 8, 1842 printed in the September 8, 1842 issue of the Smith County Democrat, page 3, column 5. A copy of the article is also available in the vertical files at the TLSA, filed under “Burke.”

[4] TSLA Microfilm, Jackson Co., TN Roll No. 53, folder titled “Burke John G. & others vs Brooks R. V. & others, Chancery 1884,” Original Complaint dated 28 July 1884. See also Family History Library Film # 985,278.

[5] Notice of Jane’s application for dower was required because every heir at law had an undivided ownership interest in John’s land. Because John died without a will, his estate was subject to the Tennessee law of intestate descent and distribution. Such laws provided that property was distributed to all heirs, with different treatment among the states between real and personal property and between children and the widow. Here is an article about legal issues relevant to genealogy.

[6] I obtained a copy of the ad via snailmail back in the pre-internet era. The TSLA staff had a really hard time finding it, and the librarian who mailed it to me wasn’t exactly clear about which newspaper she found the notice in. Here’s to the good ol’ days.