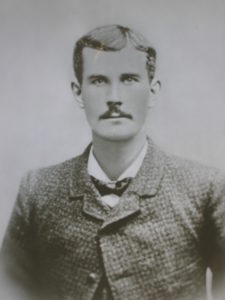

The last three articles on this blog have been about William G. Rankin, nicknamed “Willie G” by the two of us. He was apparently displeased with the nickname, see the most recent post about him here.

This post is almost, but not quite, a traditional outline chart. It has some commentary and includes minimal evidence. Three important legal documents — a probate court petition to sell the land of Robert C. Rankin as well as two wills — are abstracted at the end of the chart.

The probate court petition illustrates an important research point: one of the best things that can happen to a family history researcher is to have an ancestral family member die intestate, without children, and leaving an estate. The decedent’s property will pass to his or her heirs under the jurisdiction’s law of intestate descent and distribution. ALL of the heirs will be named in the inevitable petition to sell land or other request of the court. Any such request involving the decedent’s estate must, as a matter of law, name all heirs and make them parties to the proceeding. Thus, a petition to sell land (for example) of a childless decedent will name his or her parents if living, surviving siblings, children of deceased siblings, and –here’s a real bonus! — identify their locations. I conclusively proved a great-great grandmother when I found such a petition on microfilm, and did several twirls of my swivel chair with my arms in the air in the Family History Library in SLC. Everyone on the row grinned, knowing what had just happened.

When we found a petition to sell the land of R. C. Rankin among the probate papers of Mercer County, Pennsylvania, we had found the equivalent of the Rosetta Stone for this family.

I tracked this family trying to find a living Rankin male who might be willing to Y-DNA test. No luck. Ah, well, maybe next time. Meanwhile, here’s the chart, along with abstracts of the relevant legal documents following the chart.

See you on down the road.

Robin

1 William S. Rankin, b. abt. 1786, d. 1857, Mercer, Mercer Co., PA. The 1850 census says he was b. PA, although an abstract of his son William’s death certificate says he was born in Scotland. What makes the latter somewhat plausible is that his son William has the middle name “Galloway.” On the other hand, typical immigration and migration patterns make PA seem more likely than Scotland. His will left everything to his wife in fee simple except for a small gift to their housekeeper.[1] His wife was Martha Jane Cook, b. abt. 1790, Washington Co., PA, died in Mercer in 1873.[2] She is buried in the Mercer Citizens Cemetery along with her husband, one daughter and SIL, and three sons.[3] Six of her eight children predeceased her. She was a daughter of Robert Cook and his wife Mary (probably Mary Ann, see the first Rankin daughter) of Cecil Township, Washington County. Her father left her $250 when he died in 1826.[4] William S. most likely also lived in Cecil Township when they married, but I cannot identify him among the legion of Rankins there.

2 Mary Ann Rankin, b. abt. 1814, died 1850-55. Husband Benoni Ewing, b. abt 1807. At least one census called him Benjamin, but three legal documents are clear that his name was Benoni. The Ewings lived in Crawford Co., PA.[5]All of their children are named in several documents except for Samuel, who died young and who only appeared in the 1850 census.[6]

3 William R. Ewing, b. abt 1837.

3 James M. Ewing, b. abt 1839.

3 Elizabeth Ewing, b. 16 Nov 1842, Hartstown, Crawford Co., PA, d. 6 Jan, 1901, Mercer, Mercer Co. Husband James Alexander Stranahan, b. Philadelphia, 1839, d. 1922, Harrisburg, Dauphin Co., PA. They were married in 1874.[7]He was a Civil War veteran. Both are buried in the Mercer Citizens Cemetery.

3 Martha Jane Ewing, b. abt 1846.

3 Robert Rankin Ewing, b. 18 Oct 1847, Hartstown, PA, d. 19 Jan 1939. His Mercer Borough, Mercer Co. death certificate identifies his middle name and his parents as Benoni Ewing and Mary Ann Rankin.

3 Samuel Ewing, b. abt 1849, d. by 1856.

3 Margaret E. (probably Emma) Ewing, b. abt 1861.

2 Robert C. Rankin, b. abt 1816, d. 22 Jan 1855. His middle name was almost certainly Cook. He was an attorney. Lived at home with his parents and accumulated a fair amount of land, including mineral rights in some coal seams. Never married. He died intestate and without issue, which is conclusively proved by a petition to sell his land after he died. Buried in the Mercer Citizens Cemetery in the borough of Mercer, PA.[8] Claims on Find-a-Grave that he fought in the War of 1812 and that he had a wife and son are readily disproved, see the abstract of the petition, below.

2 James L. Rankin, b. 1820 – 1825, d. by 1855. Wife Madeline Williamson.

3 James Lee Rankin Jr., 14 Apr 1846 – 30 Sep 1933. His death certificate gives his parents’ names as James Lee Rankin and Madeline Williamson.[9]

4 James Rankin (possibly James Lee III?), b. abt 1876.

4 William Scott Rankin, b. Nov 1882, d. May 1931.

5 William Scott Rankin Jr., b. 2 Sep 1928, d. 8 Jul 1954. He was a pilot training instructor and died in a plane crash. Buried in the Laurel Grove Cemetery North, Savannah, GA.

2 John H. Rankin, b. abt 1820, d. 1872. Will dated 30 Nov 1870, proved 28 Aug 1872. Mercer Co. Will Book 6: 31. His mother was living with John in the 1870 Mercer Co. census, in which he valued his realty as $38,000. He had purchased several tracts from his brother Robert’s estate. John’s estate is recorded in File No. 3428, Mercer Co. He is buried in the Mercer Citizens Cemetery with his brothers Robert C. and William G., sister Mary Ann Rankin and her husband Benoni Ewing, and his parents Martha Cook and William S. Rankin.[10]

2 William Galloway Rankin, 1822 – 1891, Manhattan. Captain, U. S. Army with a checkered career. Married at least once, no known children. See three blog articles about him at the links in the footnote.[11] Find-a-Grave information about him is mostly incorrect.[12]

2 Samuel H. L. Rankin, b. about 1823. Probably died in the Civil War. Was in New York City in 1855 and 1860. He was listed in the household of the William Snell family in the 1860 census along with his 5-month old son. His occupation was listed as “shoe store.” His wife was probably Caroline Snell.

3 William S. Rankin, b. 7 Feb 1860, New York City, d. 21 Oct 1902, White Plains, NY. He was listed with Samuel in the 1860 census. They were living in the household of William Snell, whose family included a probable daughter Caroline Snell. In 1870, William S. Rankin and Caroline Snell Rankin were again listed in NYC in the household of William Snell, but without Samuel Rankin. Caroline and William are both buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. William was confirmed in the Anglican church, which would undoubtedly have horrified his dyed-in-the-wool Presbyterian forbears.

2 Martha Jane Rankin, b. March 1829, d. 1906. Husband Rev. William A. Mehard, 29 Oct 1825 – 24 Jun 1878. Both are buried in the Oak Park Cemetery in Lawrence Co., PA.[13] Their children are proved by the wills of her mother and her brother John.

2 Clark D. Rankin, b. abt. 1831, d. 1864-1869. Medical degree from Western Reserve College, Ohio, in 1848. Moved to Peoria, Peoria Co., Illinois.[14] Appeared in the Peoria City Directory in 1861, occupation: physician, practicing at 12 S. Adams St., residence at 138 Fulton. Commissioned in the Union Army 28 Oct 1861 as a surgeon, 7th Cavalry, Company S. Resigned his commission on 1 Jun 1862. 1863 Civil War Draft Registration indicates he was age 32 and single. His mother bequeathed $500 to her granddaughter “Martha Jane Mehard … at the request of my son Clark D. Rankin, dec’d, contained in the last letter I received from him immediately before his death.”

* * * * * *

Petition of William S. Rankin, administrator of the estate of R. C. Rankin, to sell decedent’s real estate. Mercer Co., PA Orphans Court Vol. E: 307 et seq.

Presented at the Orphans Court held at Mercer on 26 Apr 1856. Petition asserts that Robert C. Rankin, Esq., late of Mercer Borough, dec’d, died on 22 Jan 1855 in Mercer intestate and without issue. Never married. His father, William S. Rankin (petitioner), and his mother, petitioner’s wife Martha, are both now living.

Collateral heirs are his siblings and children of deceased siblings:

- Children of his deceased sister, Mary Ann Rankin, who married Benoni Ewing. Their children are William R. Ewing, James Ewing, Elizabeth Ewing, Martha Ewing, Robert Ewing, and Emma Ewing, all minors not yet having anyone legally authorized to take charge of their estate. They reside in Hartstown, Crawford Co., PA.

- James L. Rankin, a minor child of deceased brother James L. Rankin. He has no guardian and resides with his mother Madaline Julia Rankin in Reading, Cumberland Co., PA.

- John H. Rankin, a brother, of West Salem Township, Mercer Co.

- William G. Rankin, a brother, who is a deputy quartermaster in the U. S. Army. When last heard from, he was at Ft. Reading, California, and was about to remove to Fort Vancouver, Washington, Territory.

- Clark D. Rankin, a brother, who resides in Peoria, Illinois.

- Samuel H. L. Rankin, a brother, who lives in the City of New York.

- Martha J. Rankin, a sister, who is married to Rev. William Mehard. They live in New Wilmington, Laurence Co., PA.

Robert owned land and ” equitable interests” in real estate in Mercer.[15] Debts when decedent died were about $4,757; he had personal property worth $1,500. Petitioner asks to sell land, repay debts, and distribute the balance pursuant to the PA intestate distribution law. Petitioner says that a better price can be obtained at a private sale rather than a public sale. Petitioner also prays for notice to heirs and legal representatives.

On August 31st, the heirs and legal representatives accepted notice of the petition and joined in the prayer to sell decedent’s real property at private sale. The signatories were Sam H. L. Rankin, John H. Rankin, William G. Rankin, Martha Rankin, Madeline J. Rankin for James L. Rankin, William R. Ewing, A. Cook (probably Absalom) as attorney for the Ewing children, William A. Mehard, and Martha J. Rankin Mehard. Sale was ordered.[16]

The Orphans Court entries continue with the petition of J. H. Robinson, administrator de bonis non of R. C. Rankin. The petition say that William S. Rankin, Esq., late of Mercer, was administrator of Robert R. Rankin but is now deceased. The decedent’s real estate was sold at private sale on 4 May 1857 to John H. Rankin, 4 tracts. Other tracts were sold to James A. Hunla, William Struthers, and Chauncey W. Hummason. There was additional information having no apparent genealogical value.

* * * * * *

Will of John H. Rankin of Mercer Borough, Mercer County, PA. Dated 30 Nov 1870, proved 28 August 1872. Mercer Co., PA Will Book 6: 31.

To my mother Martha Rankin, the proceeds of my farm in Findley Township until sold and the use and occupation for her life of the house where she resides in Mercer Borough. The latter is already arranged for by agreement.

To my brother William G. Rankin $16,000.

To my sister Martha J. Mehard, $6,000. To her children, my niece and nephews, Emma Mehard, William Mehard, Joseph Mehard, and Charles E. Mehard, $10,000 to be equally divided when each reaches age twenty-one. Interest on those legacies while unpaid to my sister Martha for their education and support.

To brother-in-law Benoni Ewing, $1,000, and to my nieces and nephews, the children of my sister Mary Ann Ewing, $15,000: William R. Ewing, James M. Ewing, Elizabeth Ewing, Martha Jane Ewing, Robert Ewing, and Emma Ewing. Emma’s share to be paid when she reaches age 21. To the daughters, all my sheep.

To my sister-in-law Madeline J. Rankin, widow of my brother James L. Rankin, $1,000. To my nephew James L. Rankin, his son, $2,500.

Cousin Sarah Henry, wife of James Henry, $200.

Caroline Fritz, $500 and her choice of my cows.

To the Second United Presbyterian Church of Mercer, “in ecclesiastical connection with the United Presbyterian Church of the United States,” $500.

All bequests except as otherwise directed within a year of my death.

Residue to my brother and sister and nephews and nieces. Provides for the contingency that “his brother shall die without lawful issue,” telling us that Willie G (William Galloway Rankin) had no children when John H. wrote his will in 1870.

* * * * * *

Will and codicil of Martha Rankin of Mercer Borough, Mercer County, PA. Dated 6 Jan 1872, proved 26 May, 1873. Mercer Co., PA Will Book 6: 84.

Directs executors to convert government bonds, notes, and other securities into cash, and sell all personal property not disposed of herein, as soon as practicable.

To son-in-law Benoni Ewing and to my grandchildren William Ewing, James Ewing, Elizabeth Ewing, Martha Jane Ewing, Emma Ewing, and Robert Ewing, children of Benoni and my deceased daughter Mary Ann Ewing, $1,200 to be divided equally among them.

To my daughter Martha Jane Mehard, wife of Rev. W. A. Mehard, $1,000.

To my son William G. Rankin, $600.

To my grandson James L. Rankin, son of my deceased son James L. Rankin, $600.

Grandson William Rankin, son of my deceased son Samuel H. L. Rankin, $600.

To my son John H. Rankin, $125 for purchasing a gold watch for his use.

To my granddaughter Emma Mehard, daughter of my daughter Martha Jane Mehard, $500. “I make this bequest to her at the request of my son Clark D. Rankin, decd. contained in the last letter I received from him immediately before his death … to be expended upon her education.” If she dies a minor, then spend the bequest on the education of her brothers William, Joseph, and Charles Mehard.

To the above three brothers, $150 to be divided equally.

To Caroline Fritz, $500 and a good, new feather bed and bedding.

To the Second United Presbyterian Church of Mercer, $50 to be applied to its debts. And to the church’s Board of Foreign Mission, $100.

Granddaughter Martha Jane Ewing, my silver tea spoons. Granddaughter Emma Ewing, a large silver tablespoon and one feather bed and bedding. Granddaughter Emma Mehard, a large silver table spoon. Granddaughter Elizabeth Ewin, a large parlor looking glass.

Friend William J. McKean, executor. Witnesses A. J. Greer and J. W. Robinson.

Codicil dated 23 May 1873, also proved 26 May.

To daughter Martha J. Mehard, one bed and bedding, one cherry wardrobe, a large chair given me by my son John, dec’d. Also my knitted shawl, best dress, and breast pin.

To Caroline Fritz, one bed and bedding, one set of knives and forks, one rocking chair, the dishes in the cupboard and ornaments on the mantle, and one spring mattress and $100.

To Martha J. Ewing, one bed and bedding and one set of German silver tea spoons.

To Martha and Emma Ewing, one set of large table spoons.

Granddaughter Emma Mehard, $100.

Witnessses John Pew, A. J. Greer.

* * * * *

[1] Mercer Co., PA Will Book 4: 188, will of William S. Rankin of Mercer Borough, Mercer Co., PA dated 13 May 1857, proved 26 Jun 1857. $100 to Caroline Fritz, the Rankin housekeeper. Entire residue to wife Martha. Son John H. Rankin, executor. His Find-a-Grave memorial has no image of his tombstone.

[2] Mercer Co., PA Will Book 6: 84, will of Martha Rankin dated 6 Jan 1872, proved 26 May 1873. When she wrote her will, only three of her eight children were still alive: John H., William G., and Martha R. Mehard. Her son John H. died before she did, but she did not revise her will. An abstract of her will can be found above.

[3] Martha Rankin’s Find-a-Grave memorial can be found at this link. There is no tombstone image.

[4] Washington Co., PA Will Book 4: 282, will of Robert Cook of Cecil Township dated and proved on 8 May 1826. Wife Mary. Sons John and Archibald. Daughters Jane Long, Martha Rankin, and Margaret Clark.

[5] 1850 census, Crawford Co., PA, household of Benjamin Ewing, 42, Mary A., 36, William R., 13, James M., 11, Elizabeth, 7, Martha J., 4, Robert, 2, and Samuel, 1, all b. PA. 1860 census, Crawford Co., Benoin [sic] Ewing, 54, merchant, $5,000/$10,000, William Ewing, 23, clerk, James Ewing, 21, clerk, Robert R. Ewing, 12, Elizabeth Ewing, 17, Martha J. Ewing, 14. 1870 census, Hartstown, Crawford Co., PA, Benoni Ewing, 63, $11,500-$700, Elizabeth Ewing 23, Martha J. Ewing 23, Robert R. Ewing 22, and Margaret E. (presumably Emma) Ewing 19, all b. PA.

[6] See Mercer Co., PA Orphans Court Vol. E: 307 et seq., petition to sell the land of Robert C. Rankin, dec’d, names the children of his deceased sister Mary Ann Benoni: William R., James, Elizabeth, Martha, Robert, and Emma, all minors in 1856.

[7] Elizabeth Stranahan’s Find-a-Grave memorial has an image of her death certificate.

[8] The Find-a-Grave memorial for Robert C. Rankin claims that he was in the War of 1812, which cannot be correct. He was born about 1816, according to the 1850 census when he was living with his parents in Mercer County. It also claims that he had a wife and son, which is disproved by the petition to sell his land after he died. Robert’s Find-a-Grave memorial can be found at this link.

[9] 1880 census for Savannah, GA, James L. Rankin, 34, b. GA, mother b. GA, father b. PA, with wife Susie S. Rankin and son James, 4.

[10] Here is John H. Rankin’s Find-a-Grave memorial.

[11] The first two articles about Willie G. can be accessed here (part 1), and here (part 2). A link to the most recent article, part 3, is provided in the first paragraph of the main article text.

[12] William G. Rankin’s Find-a-Grave memorial is at this link. The posted attempted to put an unwarranted gloss on his military career.

[13] 1860 census, Lawrence Co., PA, W. A. Mehard, 35, Martha Mehard 30, Emma Mehard 4, William Mehard 1. 1880 census, William Mehard 54, Martha Mehard 49, Emma Mehard 23, William Rankin Mehard 20, Joseph H. Mehard, 18 and Charles E. Mehard, 12.

[14] See 1855 Illinois State Census, Clark D. Rankin, age 20 < 30, b. 1825 – 1835.

[15] The Mercer Co. real property owned by Robert C. were: (1) a 133-acre tract in Findley Township known as the “Tait Farm;” (2) an 85-acre tract in Findley Township; (3) a 76-acre tract in East Lackawannick Township; (4) 9 acres and (5) 4 acres in the same township; (6) 25 acres in Sandy Lake Township; (7) an undivided 1/2 interest in 3.5 acres of the Common Coal Bank in West Salem Township underlying a 190-acre tract of which decedent owned 12 acres. The petition has information about adjacent landowners for each tract. Mercer Co., PA Orphans Court Vol. E: 307 et seq.

[16] Mercer Co., PA Orphans Court Vol. E: 307 at 308-309.