The speed of this article will be a function of how fast I can type, since I’m not going to be encumbered by a time-consuming evidentiary trail. This is coming straight out of memory. Here’s why I’m writing it …

I exchanged a few texts with one of our sons a few days ago. He sent a picture of a statue from a city he is visiting. He said it reminded him of “James Rankin.”

– Did autocorrect change “Jim” to “James,” I asked?

No response. I continued.

– If you are thinking of your grandfather, his full legal name was Jim Leigh Rankin.

I gave it some more thought.

– “Leigh” is pronounced “LAY,” not “LEE.”

– “Right!” he responded.

This gave me a jolt: perhaps I have not kept my genealogical eye on the ball. I have written a ton of articles about Rankins. However, I have evidently failed to tell my sons much about their Rankins — to the point that one son didn’t know his Rankin grandfather’s actual name.

Perhaps I have not written about my father because it is so personal. I adored him, as will soon become obvious. Whatever. Here is his story, and I will strive not to libel too many of his relatives.

* * * * * *

Jim Leigh Rankin about 1955

If I just stick to the facts, his story will be short and sweet. He was born in rural north Louisiana, grew up poor, went to work, married, had one child, was successful, retired, and died.

Well, perhaps that is a bit spare, since it applies to a great many people. As I consider it, though, his life to me was a series of vignettes. A very quiet man, he said little. I can count on my digits the number of long-ish talks I had with him, and I wouldn’t be in any danger of running out of fingers. I learned about him mostly from observation and stories from other people.

Here’s a better outline. He was born in 1907 in Cotton Valley, Webster Parish, Louisiana. He grew up in Gibsland, Bienville Parish, which is famous only for being near the place where Bonnie and Clyde were shot. That part of North Louisiana probably hasn’t changed much since the Depression. It was still pretty grim the last time I drove through the area.

He was the youngest of four siblings. The family was poor as church mice. His father, John Marvin Rankin (“Daddy Jack,” my cousins said he was called) was not a successful provider. He was briefly the Sheriff of Webster Parish, a waiter, and the driver of a dray wagon. Their home was rented. His wife, Emma Leona Brodnax Rankin (“Ma Rankin,” or just “Ma”) took in mending to help supplement whatever he earned.

I once asked Butch, a Rankin first cousin, what Daddy Jack did for a living. Butch had a quick answer: “Anything he could, hon. Anything he could.” There was an old popcorn cart stored under the rear of their house, which was built on a fairly steep slope. Daddy Jack undoubtedly peddled popcorn at one time, perhaps turning a profit when all the tourists came to gawk at the corpses of Bonnie and Clyde, laid out in the coroner’s office in Gibsland.

Prior to my father’s generation, our branch of the Rankin family hadn’t had more than two nickels to scratch together since my great-great-great-great grandfather Samuel “Old One-Eyed Sam” Rankin, a wealthy owner of land and enslaved persons, died circa 1816 in Lincoln Co., NC. My line didn’t share any of the estate’s largesse. Sam’s son Richard, from whom we descend, died in serious debt before his father.

See, this is how I go off the rails about family history. Our sons go MEGO (“my eyes glaze over”) when I spout this stuff. I will try to stay on track.

Ma Rankin was a grim, tea-totaling, Southern Baptist, charitably described by my much older cousins as “strict.” I avoided her and her stultifying, overheated house to the extent I could get away with it. She once stopped a desultory conversation dead in its tracks, a bullet through its brain, with three of her four children and several grandchildren trapped in her living room. My Uncle Louie attempted to break yet another long silence:

– well, the Russians have launched a satellite. Next they will be sending a man to the moon.

– If God had intended for man to be on the moon, pronounced Ma, He would have put him there.

Her arms were crossed. She was dead serious. My cousins and I fled to the yard, where we pelted each other with pecans. Perhaps not surprisingly, Ma’s children all turned out to be nonbelievers.

Ma Rankin was born into a wealthy family which survived losses of impressive fortunes during what some Southerners just called “the War.” Her Brodnax ancestors in this country stretch back to a couple buried in the Travis Family burying ground on Jamestown Island. In England, her line goes back to landed gentry in Kent. The Bushes also descend from the Jamestown Brodnaxes.

One of Ma Rankin’s brothers, Uncle Joe Brodnax, had the sense to acquire a bunch of mineral rights in north Louisiana. The land was located over a prolific oil and gas play. He evidently left a nice legacy to his sister Emma “Ma” Rankin. Among other things, they finally owned a house.

Daddy’s three older siblings all had college degrees. He didn’t go to college because, he explained, “the money ran out.” Presumably, he was referring to Uncle Joe’s legacy. Instead, he started playing what he called “semi-pro ball” after he graduated from high school. I took that to mean what would now be minor league professional baseball. (I wasn’t adept at the art of cross-examination when I heard these stories.) A lefty himself, he was released after a game when a left-handed pitcher struck him out in four at-bats.

He then went to work in the gas fields as a “chart changer’s helper” for a natural gas transmission company. It didn’t take someone too long to notice he was smarter than everyone else and had a prodigious, and I mean remarkable, memory. Also a marked ability for math. In the wink of an eye, he ascended the field ranks to become the Monroe area gas dispatcher. That meant he went out to the field when and as needed, 24/7/365, to open or close valves on the company’s gas transmission system.

Soon thereafter, he was transferred to the company’s headquarters in Houston, where he became the national expert on gas proration. I won’t explain what that is, because it would cause serious MEGO. Instead, I will just say that a man who worked for him for a quarter-century told me Daddy “wrote the gas proration laws for Louisiana, Texas, and Mississippi.” That was clearly an exaggeration, since he wasn’t a lawyer. But that statement contains a large element of truth. He was a regular witness testifying about gas proration before legislative committees and regulatory commissions in those states. His questioners must have been patient, because he spoke slowly and quietly, using as few words as possible.

He met my mother in Houston at the natural gas transmission company where they both worked. She was a typist/secretary in the stenography department. From time to time, she would go take dictation from him and type it up. He chewed tobacco. My mother, unaccountably, thought that was cute. They were relatively old when they married in 1936: 26 and 29. They were a decade older when they became parents for the first and only time.

Jim and Ida in Southside Place, Houston, circa 1937

His work brings a couple of vignettes to mind. I remember his frequent trips out of town. My mother and I would go see him off at the Shreveport airport — United Gas moved its headquarters there in 1940. This story is set in 1951. Eisenhower, still aglow with his WWII success, was running for President. He was making a stop in Shreveport for a campaign appearance, and the airport was packed by the time my parents and I arrived. Daddy was flying on a DC-3, a two-engine affair which had a folding door containing steps for boarding.

At the top of the boarding steps, Daddy turned to face the crowd, lifted his hat with his left hand, and flashed the “V” for “Victory” sign with his right. The crowd roared its approval.

Another vignette: after Texas passed its gas proration laws, producers had to calculate something called “allowables,” the amount of gas which they could legally produce. Daddy went to Austin frequently to testify in rate cases or whatever the current issue may have been. He stayed in the Driskill, still a lovely old hotel with a fabulous bar. Those oil and gas guys would head to the bar at the end of the day. Every evening, at least one producer would accost him with, “Hey, Jimmie, I’ll buy you a drink if you’ll calculate my allowables for me.” I seriously doubt that he ever paid for a drink.

Another vignette from before I was born, related by my mother. He returned home early one morning from a train trip to Baton Rouge. My mother found a metal door plaque identifying a men’s restroom under the bathroom mat. She accosted him with the evidence, with some asperity.

– Jimmie, what on earth is this doing here?

– I don’t know … we were having a pretty good time, and I didn’t know where else to put it when I got home.

Train car bars weren’t as classy as the Driskill, but the bourbon probably tasted the same. I wish she had saved the damn sign.

Here are a couple more vignettes, featuring the sense of humor he displayed as a pretend celebrity at the airport in 1951.

We were having our weekly dinner at Morrison’s Cafeteria in Shreveport. Daddy turned to me conspiratorially.

– There were a bunch of bees flying down a highway. They needed to stop. They passed by a Gulf station, a Texaco station, and a Shell station. They finally turned in to an Esso Station.

(That was Standard Oil of Ohio at one time. I think).

– Why do you think they passed up the first three stations for the Esso station, my father asked me, a perfect 14-year-old straight man.

– I don’t know, Daddy.

– Because they were SOBs, he chuckled.

– Jimmie! my mother said reprovingly, suppressing a grin.

Another family meal, but this time I was 18 or 19, home from school for a holiday. It was the three of us in a local Mexican restaurant, plus my maternal grandmother Ida Burke.

Granny examined me with a mildly disapproving look and pronounced her verdict.

– Robin looks just like her father.

I can understand some disappointment: my mother was a world-class beauty.

Without missing a beat, Daddy turned to me and patted me on the arm.

– Of course she does!!! That’s why she’s so pretty!!!

He did enjoy rattling a Burke cage from time to time. I dearly loved my Burke relatives, but they were outmatched.

In his family, he was always characterized as a man who was too kind to swat a fly. He was the family caretaker. Needed a will probated? He was your man. Taking care of his mother when she reached the age of frequent doctor’s visit? Selling her house after she died? Ditto. Helping with whatever? Just ask.

He was bitten with what he called “the genealogy bug” after he retired in the late 1960s. My husband Gary was in pilot training at Craig AFB, Selma, AL. He and I were too poor for long distance calls (and Daddy was too frugal, and naturally disinclined to talk). Instead, we wrote letters. His regular salutation was “Dear Robin Baby.” Or perhaps it was “Dearest Robin Baby,” my memory is unclear. He and his sister Louise, who lived in Heflin, Bienville Parish — the only one of the four Rankin siblings who didn’t have the sense to get the hell out of rural north Louisiana — drove all over the area visiting relatives, collecting family stories.

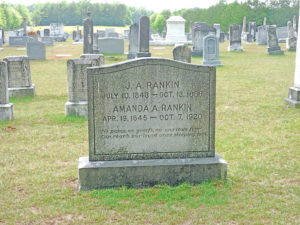

They found a good love story and a mystery about their Grandfather, John Allen Rankin. Turns out John Allen met his future wife Amanda Lindsey in 1863, when he knocked on the door of her father’s house in Monticello, Arkansas. He was reportedly looking for a sister who lived in the area. Amanda later said that she “opened the door to the handsomest soldier you ever saw and fell in love on the spot.” The mystery was why he was “already out of the War in 1863,” as Daddy put it. So he sent off for John Allen’s military records, writing to me that he would keep it a secret if there was “a skeleton in the attic.”

There was, but it’s not a secret because I’ve written about it on this blog. My Confederate great-grandfather, displaying what I consider imminent good sense after being in a losing battle near Vicksburg and approaching the second year of his 6-month enlistment, deserted. He had just been issued a new uniform and several months back pay in Selma, Alabama. He evidently walked to Monticello, where he made Amanda Lindsey swoon.

What else about Daddy? He was a sentimental sweetie who carefully saved every scrap that was important to him. I found among his keepsakes an envelope labeled “Burke’s baby tooth,” with one of our son’s teeth carefully wrapped in folded tissue paper. There was also every report card, piano recital program, dance recital program, and twice-yearly reports from the private school I attended through the third grade.

He taught me how to play baseball, of course. Better yet, he taught me how to keep score. He and I would occasionally go (just the two of us!) to a Shreveport Sports game. He encouraged me to join him in booing lustily when an umpire made a bad call, defined as most anything unfavorable to the home team. He told me that a batter would hit a foul ball 5 out of 7 times when facing a full count. One of these days I’m going to test that theory.

He had a table saw and other carpentry tools in the garage. He made a back yard high jump for me. It consisted of two upright 2″x 2″ boards on wooden stands, with nails in each upright marked at one-inch increments for height. A bamboo pole served as the horizontal piece.

He also made a fancy cage for one of my Burke grandfather’s fabulous gifts: a pair of quail. Gramps also brought me baby ducks, baby chicks, and other wildlife. Also a B-B gun and a small rod and reel.

– I swear he will bring her an elephant one of these days, said Daddy.

He was 5’7″ and 140 pounds soaking wet, but nevertheless a fine athlete. He excelled at pretty much anything he tried. As an adult, he was a good golfer and above-average bowler, as evidenced by a “250” coffee mug from Brunswick. In high school, he was on the tennis and baseball teams. He was voted “Most Handsome.” He was the editor of the high school yearbook. I suspect he took that job to make sure his name appeared therein as JIM, not JAMES. My son wasn’t the first person who made that mistake. The engraver who did my wedding invitations didn’t believe that my mother, who had been married to him for a mere 31 years in 1967, actually knew his first name was Jim. He appeared on those wedding invites as “James.”

One of my high school best friends died in Vietnam. At his 1970 Shreveport funeral, Daddy (who loved my friend) cried like a baby. He wrote to one of his genealogy correspondents — Mildred Ezell, the woman who published the definitive books on the Brodnax family — that he never wanted to hear “Taps” played again.

Roughly a quarter-century later, I exchanged emails with Mrs. Ezell. She had posted a query online asking for information about my Brodnax great-great- grandfather. I replied, identifying myself as Robin Rankin Willis. She asked me in the next email if I knew whatever had happened to Jim Rankin. He clearly made an impression.

I’m going to omit the part where he got cancer and died. I don’t think I can stand to write about it.

And that is all for now. See you on down the road.

Robin