My ancestor John Allen Rankin and his wife Amanda Lindsey have a good story. From one vantage point, it is a war story. It is also a love story. The love story and war story intersect in both my family’s legend and the verifiable facts.

My father’s “how to” genealogy book advised to begin compiling one’s family history by interviewing family members. All oral family histories have errors, but even the misinformation can provide clues, says the book.

My father promptly took that “how to” advice when he was “bitten by the genealogy bug.” He and his sister, Louise Theo Rankin Jordan, set out to talk to their north Louisiana kin. Here is what he wrote to me in a 1969 letter telling me the latest he had learned:

“Dearest Robin Baby:

….Cousin Norene Sale Robinson at Homer told us that Grandma [Amanda Lindsey] was living in Monticello, Arkansas in 1863 when she met John Allen [Rankin]. He came to their door one night looking for a sister who lived there in town. Grandma said that she went to the door and ‘there stood the most handsomest soldier that she had ever seen and that she fell in love with him right there.’ They were married some time after that.”

There is a wealth of information in that legend. Its chief virtue is that the essential objective elements – location, dates, a soldier’s uniform, the people involved – are readily subject to verification. The legend also comes from an unimpeachable source, because Cousin Norene had lived with Amanda for some time and knew her as an adult. Norene had actually heard that story straight from the horse’s mouth, so to speak. It was not subject to the vagaries of multiple oral retellings.

I set about trying to confirm the facts in the legend.

First, Amanda’s father, Edward B. Lindsey, was living in Monticello, Drew County, Arkansas in 1860.[1]During the war, he was a member of the Monticello “Home Guard,” so he was still in Monticello 1863. So far, so good – Amanda’s family was right where the legend says they would be in 1863.

However, John Allen did not have a sister who was old enough to be married or living on her own when he was knocking on Monticello doors in (according to the legend) 1863.[2] John Allen did have a married older brother, William Henderson Rankin, living in Drew County.[3] According to the 1860 census for Monticello, William was listed just a few dwellings down from Amanda’s father Edward B. Lindsey.[4] However, William was still off fighting in the War in 1863.[5] Thus, John Allen was almost certainly looking for his sister–in-law rather than a sister. As legends go, that’s close.

It is also certain that John Allen was a soldier. My father’s 1969 letter continued with the war part of the family legend.

“Cousin Norene said that [John Allen’s] war record was never discussed by the family. It does seem funny that he was out of it in 1863. I have always thought that he was wounded in the war and that was one reason he died at a fairly young age. It seems that was what we were told. So there could be a body hidden in the closet. Anyway we will find out for I am going to send off for his war record tomorrow, and if he did desert we will keep that out of the record.”

I couldn’t find the war records among my father’s materials, so I started sending off for my own copies. Amanda’s Confederate pension application, a certifiable heartbreaker, arrived by mail first. She filed it from Haynesville, Claiborne Parish, Louisiana in April 1910.[6] She was living with her daughter, Anna Belle Rankin Sale (Cousin Norene’s mother), as of 1900.[7] Amanda signed the application in the quavery handwriting of an old person although she was only sixty-five, which doesn’t seem all that old to me. The rest of it, though, is filled out in a strong feminine hand.

Amanda swore in her application that she had no source of income whatsoever, no real property, and no personal property worth a spit. That is all unquestionably true: that didn’t change until my father’s generation of Rankins. Amanda stated further that John Allen volunteered for the Confederate Army in Pine Bluff, Arkansas on March 14, 1862. Captain Henry was his company commander, and he was in the 9th Arkansas Infantry. She also swore that John Allen was honorably discharged on April 10, 1865, which just happens to be one day after Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House.

Here we have an apparent disconnect between the legend and the pension application. The legend says that John Allen and Amanda met in 1863. Amanda swore that he was discharged two years later.

The Office of the Board of Pension Commissioners of the State of Louisiana sent Amanda’s application off to the War Department in Washington, D.C. The War Department had this to say in response.

“The records show that John A. Rankin, private, Captain Phillip G. Henry’s Company C, 9th Arkansas Infantry, Confederate States Army, enlisted July 25 (also shown August 9) 1861. On the muster roll covering the period from November 1 to December 31, 1863 (the last on which his name is borne), he is reported absent in arrest in Canton, Mississippi by order of the Provost Marshal. No later record of him has been found.”

With that information in hand, the Louisiana Pension Board Commissioners rejected Amanda’s application. “Absent in arrest” means “AWOL.”

I cannot decide whether Amanda was surprised by the denial of her application. Did she think she was telling the truth about that honorable discharge? I wonder who came up with a discharge date one day after Appomattox? In my imagination, which badly wants to give the destitute Amanda the benefit of the doubt, some nice female clerk was helping Amanda fill out the application (it is, I surmise, the clerk’s handwriting on the forms). The clerk asked when John Allen was discharged, to which Amanda responded truthfully that she did not know. The clerk, who thought she knew her history, said, “well, everyone was discharged by April 10, 1865, so why don’t we just use that date?”[8] Fine, said Amanda. The clerk naturally assumed that John Allen received an honorable discharge, or why else would Amanda even bother to apply?

John Allen’s entire military record arrived next.[9] Amanda did recite some of the facts correctly. He did enlist in the Confederate army at Pine Bluff, Arkansas – near where his family farmed, in Jefferson (now Cleveland) County. He was a private, and served in both C and K companies of the 9th Arkansas Infantry. He enlisted for a one-year term on July 25, 1861.

At the beginning of the Vicksburg Campaign, the brigade of which the 9th Arkansas Infantry was a part was located at Port Hudson, Louisiana. It was ordered to Tullahoma, Tennessee on or about 15 April 1863, but was recalled on 18 April 1863 and sent to participate in the Battle of Champion’s Hill in Mississippi on 16 May 1863.

The Confederates were out-generaled at Champion’s Hill. The Confederate in charge, General Stephen Lee (no relation to Robert E.) marched his soldiers piecemeal into Grant’s entrenched position. You don’t need to be a military genius to sense this was a dumb idea. About 4,300 Confederate soldiers and 2,500 Union soldiers were casualties. It was considered a Union victory and a decisive battle in the Vicksburg campaign.

On our way home from a trip to Nashville, Gary and I drove around the area of the battle. It is a backwoods area just east of Vicksburg, almost entirely forgotten by history. There is no park and no historical markers, except a stone monument where Confederate Brigadier General Leonard Tilghman died.

On 19 May 1863, whatever was left of John Allen’s division after Champion’s Hill arrived at Jackson, Mississippi. He was in the 1st Mississippi CSA Hospital in Jackson from May 31 to June 13, 1863. The diagnosis: “diarrhea, acute.” That was near the end of the second year of his one-year enlistment.

On September 1, 1863, now in Selma, Alabama, the army issued John Allen a new pair of pants, a jacket and a shirt, all valued on the voucher at $31.00. Good wool and cotton stuff, presumably. Probably the best suit of clothes John Allen ever owned.

On October 14, 1863, the Confederate States of America paid John Allen $44 for the pay period from May 1 through August 31, 1863.

And that was the last the CSA ever heard of my great-grandfather John Allen Rankin, who probably just walked away. By November 1, 1863, he was listed as absent on the muster roll for his unit. They finally quit carrying his name on the muster roll after December 1863.

It probably wasn’t too long after John Allen was paid in Selma in October 1863 that he was talking to his future wife at the front door of Edward B. Lindsey’s home in Monticello, Arkansas. That had to have been about the middle of November 1863, assuming he covered twenty miles per day on the 400-mile trek from Selma to Monticello.

On that note, the legend takes a decided turn for the better. He was wearing an almost brand-spanking new uniform, he was the most handsome soldier Amanda had ever seen, and she fell in love on the spot.

As noted, the last record in John Allen’s file says he was “absent in arrest in Canton by order of Provost Marshall.” By the time that AWOL arrest order was issued, he was already in Monticello, Drew County, Arkansas, making Amanda Addieanna Lindsey swoon. And that is the end of the war story.

By 1870, John and Amanda were living in Homer, Claiborne Parish, with their two eldest children, Anna Belle Rankin and Samuel Edward Rankin. The couple listed $400 in real property and $350 in personal property in the census enumeration. John Allen identified himself as a farmer. They apparently owned some land, although I cannot find a deed of purchase or a land grant to John Allen. However, he and Amanda sold nine acres in Claiborne Parish for $33 in August 1870.[10]

The sale of land is perhaps a clue that farming did not work out well. By 1880, the Rankin family was living in Webster Parish.[11] John Allen, age 36, was Deputy Sheriff. He and Amanda had six children, with one more child yet to come.

The deputy sheriff job was short-lived. A letter saved by the family of John Allen’s brother Elisha Rankin reports that John Allen and family went through Homer in October 1882 on their way to Blanchard Springs to run a barber shop.[12] I don’t know what happened to the barber shop, but the Rankins wound up back in Claiborne Parish for the rest of their lives.

The next thing you know, John Allen was six feet under. According to Amanda’s pension application, John Allen died of “congestion of the brain,” an obsolete medical term. It most likely means that John Allen had a stroke. He was only forty-five years old. There were five children age fifteen and under still at home.

Amanda must not have had an easy time thereafter. Her anguish is palpable in a letter she wrote to one of John Allen’s brothers, Elisha (nickname “Lish”) and his wife Martha. Amanda wrote the letter three months after John Allen died on Sunday, October 13, 1888. She was forty-four years old. Here is a transcription, with spelling and punctuation (or lack thereof) exactly as transcribed, and question marks where the language is uncertain or totally illegible.[13]

“Dear Brother and Sister, it is with pleasure tho a sad heart that I try to answer your kind letter I received some time ago Would have written sooner but I was in so much trouble I could not write soon We had to move Dear brother you have no idea how glad I was to get a letter from you I feel like one forsaken My happiness on earth is for ever gone of course I know you grieve for the Dear (?) house (?) but oh what is the grief to be compared to misery when a woman loses her husband. How sad I feel today for the dear one was a corpse on sunday. how long seems the days and nights to me.

“Brother Lish you wanted to know how we are getting along We are in det over one hundred dollars and no hom. I have moved to Mr. Weeks to work on ????? Jimmy Burton my Nephew is going to ??? after the little boys and show them how to manage this year. Eddie [Amanda’s son, Samuel Edward] is at Harrisville [Haynesville?]. I could not depend on him to ?????? He is not settled yet. I will ???? ???? me and the children a longe time to pay our det. It was the oldest children that caused me to be so bad in det. If I was young and able to work I would feel like maybe in two or three years we wold get out of det. I will do all I can to help the boys make a crop. Joe [Amanda’s son, Joseph D. Rankin] is 16 but he don’t now how to work much. I have got a few hogs and cowes all I have got. Annie and Lula [her daughters Anna Belle and Lula, both of whom married men named Sale] married brothers. They have got good homes. They live 3 miles from me. They live in site of each other.

“Brother Lish be sure to write as soon as you get this it does me so much good to get a letter from any of you how proud I was to think you thought enough of me to inquire after my welfare tho it is quite different to what you thought it was some times I all most give up and not try to work then I think of the poor little children and no father to provide for them I try to pick up courage to work all I can for there was ????? she is no longer a pet we sent her to school last year teach come to see me about the pay I told him I could not pay it. He said he would wait untill next fall or the next year untill I could pay it ?? ??? ??? ???? ?? ???? ?? ????with me for it if she had a ??? and out of det maybe we could make a living but in det and no home ???? and little childern no father oh lord father give me

“Brother Lish I am a fraid you cant read this. It has been so long since I wrote a letter. Give Mother my love [presumably, “mother” refers to Mary Estes Rankin, the mother of John Allen and Lish] and tell her to pray for me that I ???? ???? my children ???? I will have to be Father and Mother both. Give my love to all the connection and tell them to write. My love to Martha and the children write soon and often I remain ever ?????? ???? Sister.

Amanda Rankin”

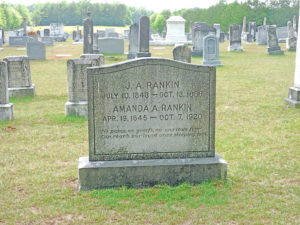

May you rest in peace, Amanda and John Allen. Both are buried in the Haynesville Cemetery in Claiborne Parish, Louisiana.

See you on down the road.

Robin Rankin Willis

* * * * * * * *

[1] See “Edward Buxton Lindsey: One of My Family Legends” here.

[2] John Allen had two sisters, Mary and Elizabeth (“Lizzie”) Rankin. 1860 census for Jefferson Co., AR, dwl. 549, listing for Samuel Rankin included Mary Rankin, age 10; 1870 census, Jefferson Co., AR, dwl. 17, listing for Mary F. Rankin (Sam’s widow) included Elizabeth Rankin, 8. The elder daughter, Mary, would only have been about thirteen in 1863.

[3] Jennie Belle Lyle, Marriage Record Book B, Drew Co., Arkansas (Little Rock: Democrat Printing & Lithography Co., 1966), William H. Rankin, 20, married Eliza Jane Law, 21, July 1, 1858.

[4] 1860 federal census, Drew Co., AR, dwelling 155, listing for William Rankin and dwelling 167, E. B. Lindsey.

[5] William H. Rankin’s service record at the National Archives indicates that he enlisted from Monticello in the Confederate Army on 8 Feb 1862 for three years or the duration of the war. He was listed as present on his company’s muster roll through Oct. 31, 1864.

[6] Louisiana State Archives, “Widow’s Application for Pension” of Amanda A. Rankin, widow of John A. Rankin, P.O. Haynesville, LA, filed 4 Apr 1910.

[7] 1900 federal census, Haynesville, Claiborne Parish, LA, household of A. C. sale with mother-in-law Amanda Rankin, wife Annie Sale, and children.

[8] That’s not quite accurate. Some fighting continued after Lee’s surrender on April 9.

[9] National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Civil War record for Rankin, John A., Companies C and K, Arkansas Infantry, Private.

[10] FHL Film # 265,980, Claiborne Parish Deed Book J: 226.

[11] 1870 census, Webster Parish, LA, dwl 255, J. A. Rankin, wife Amanda Rankin, and children Anna Belle, Edward, Lulu, Joseph, Marvin, and Melvin.

[12] Letter from Washington Marion Rankin (“Wash”), who lived in Homer, to his brother Napoleon Bonaparte (“Pole”) Rankin dated October 1882. See Note 13.

[13] I do not own, and have never seen, the original of the family letters. I obtained a transcription from Megan Franks, a descendant of Elisha Rankin, John Allen’s brother. Another distant cousin reportedly owns the original of Amanda’s letter, as well as several other Rankin letters from the 1880s. I called and wrote to him (he lives in Houston) but he did not respond.