My mother’s family has produced so many men named William Logan Burke that we had to create nicknames to keep them straight. The first William Logan Burke (1860-1899) was simply “the Sheriff.”

His son, who was inter alia a polo player, was “W. L.” or “Billy” Burke (1888-1961) — AKA “Gramps,” my grandfather.

The next son in line was also a polo player, nicknamed “the Kid” (1914-1975) — AKA “Uncle Bill.”

The Kid’s elder son — our collective imagination failed here — was “Little Bill” (1952 – ?).

The fifth and possibly last of the name is Little Bill’s nephew. He has several brothers, all of whom are grown and might yet produce a sixth William Logan Burke.

They all have stories, with a couple of family legends in the mix. There has been a recent trend toward tragedy. I’m rooting for the most recent of the Sheriff’s namesakes to turn the luck around. As usual, I won’t write about anyone who might still be living.

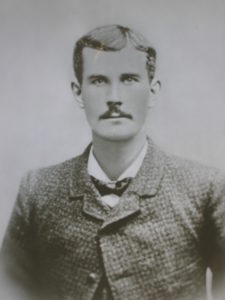

Here is the Sheriff:

He was born in Wilson County, Tennessee in 1860, the eldest son of Esom Logan Burke and his wife Harriet Munday. Not inclined to be a farmer, he left for Texas shortly before his father died. He wound up in Waco, McLennan County, where he was “an early sheriff” and a U. S. Marshall. He died of tuberculosis at age 39, leaving his widow Betty and their 11-year-old son, the second WLB.

Here is his wife, Elizabeth (“Betty”) Morgan Trice.

According to my grandmother Ida Hannefield Burke, Betty had red hair and “could hold her liquor like a man.” The Hannefields also lived in Waco. Granny told me she always “felt sorry for Mrs. Burke.”

“Why?” asked I.

“Because the Sheriff was gone so much,” said Granny.

“Why was that?”

“I don’t know,” Granny replied. “Out chasing criminals, I suppose.”

Betty Trice’s family also came to Waco from Wilson County, Tennessee. The Burke and Trice families undoubtedly knew each other there, since both owned land on a lovely tributary of the Cumberland River called Spring Creek. Betty’s father, Charles Foster Trice, died in a cave-in of the creek bank in 1881, when she was 18. His estate was insufficient to cover debts and his land was sold, probably providing the impetus for his family to head for Texas.

Before Foster died, though, he and his wife Mary Ann Powell Trice gave rise to a cool family legend. Wilson County is in Middle Tennessee, a part of the state that was not partial to either side in the Civil War. The Union Army had a headquarters nearby and sent a “recruiting” detail around from time to time, looking for “volunteers.” Hearing they were in the neighborhood, Mary Ann dressed Foster up in a woman’s dress and bonnet. She sat him down in front of the fire in a rocking chair, peeling potatoes. The Union soldiers departed empty-handed.

Mary Ann lived to be 95. She died in Waco when her great-granddaughter, Ida Burke, was 18 years old. Ida, my mother, told me she heard that story straight from Mary Ann’s mouth. So it is the gospel truth, in my view.

Berry and Sion Trice, two of Mary Ann’s brothers-in-law, also went to Texas. They walked all the way from Wilson County to Waco — about 900 miles — in 47 days, according to William Berry Trice’s obit. Berry was also famous for weighing 425 pounds when he died, as well as having been a director of the Waco National Bank. Berry and Sion were partners in a Waco brickmaking company. It supplied most of the nearly three million bricks used to build the bridge over the Brazos River in Waco. The bridge was completed in 1870 and was then the longest single-span suspension bridge west of the Mississippi; it was part of the Chisholm Trail. Baylor has some fun photographs and postcards of the bridge at this site.

The Sheriff, his wife Betty Trice Burke, her mother Mary Ann Powell Trice, the Hannefields, and a whole host of other Trices are buried in the old Oakwood Cemetery in Waco. Not surprisingly, Sion and Berry have impressive monuments. Made of marble, not brick.

The Sheriff and Betty had only one surviving child, the second William Logan Burke: the polo player, Billy or W. L. Burke, AKA Gramps. He was an orphan by age 18, when his mother died. He went to live with one of his mother’s sisters, his Aunt Mattie Trice Harmon. Here is Gramps in his sixties as a referee in a polo match:

Gramps was the spitting image of his mother, IMO. Here he is as a young man:

Besides eventually becoming the oldest polo referee in Houston, Gramps was a Grade AAA, certifiable, lovable character. Whenever he came to Shreveport to visit his daughter Ida, he brought gifts for me. He started with an add-a-pearl necklace, undoubtedly Ida’s idea. He soon switched to various livestock: ducklings, baby chicks, and — my favorite — two quail. My father built an elaborate cage for the pair in the back yard. Unfortunately, the quail commenced their characteristic “bob-WHITE!” call just before the first light of dawn. They had extraordinary lungs. The neighbors complained. One night, the quail “escaped.” I don’t recall what happened to the cage.

My father was fond of saying that Gramps would probably bring an elephant one day.

Besides being a polo player, referee, and trainer of polo ponies, Gramps was a hunter and fisherman. He also raised bird dogs, including a prizewinner named April Showers. Gramps taught me how to shoot a BB gun at a moving target by hanging a coffee can lid from a tree limb by a string. The gun was another gift from Gramps, as was a small rod and reel. Never mind that my parents didn’t fish.

The Sheriff’s grandfather back in Tennessee was a John Burke whose first wife was Elizabeth Graves, daughter of Esom Graves and Ruth Parrot. John Burke was known as a teller of tall tales. If that is an inherited talent, Gramps most likely got it from his great-grandfather John. Granny once sent Ida a newspaper article she had torn out of one of the Houston papers, date unknown. Granny had written on the article in pencil, “Your father in print with a big one.” It was in a column titled “The Outdoor Sportsman” by Bill Walker. I have transcribed it on this blog before, but here it is again. Cinco Ranch is west of Houston.

“A roaring gas flame in the big brick fireplace in the Cinco Ranch clubhouse warmed the spacious room and the several members of the Gulf Coast Field Trial Club who gathered there for coffee Saturday morning before the first cast in the shooting dog stake.

“Usually when veteran field trial followers get together the conversations turns to great dogs of yesteryears and this group was no exception.

“W. L. “BILLY” BURKE related one about an all-time favorite of ours — Navasota Shoals Jake.

“Burke and the late W. V. Bowles, owner of Ten Broeck’s Bonnett and Navasota Shoals Jake, were hunting birds in the Valley on one of those rare hot and sultry winter mornings. Jake pointed a covey several hundred yards from the two men and out in the open.

“BOWLES suggested they take their time approaching the pointing dog, since he was known to be very trustworthy. When the two hunters did not immediately move to Jake, the dog broke his point, backed away to the cool shade of a nearby tree and again pointed the birds.

“THE COVEY was still hovering in a briar thicket when Bowles and Burke arrived. Navasota Shoals Jake was still on point.”

Gramps’s only son, the third William Logan Burke, was nicknamed “the Kid” by other polo players, presumably in recognition of his father and the family sport — but also for his wild and reckless polo style, according to his sister Ida. That was Uncle Bill.[1]

He was good. According to Ida, West Point recruited him to play polo, but West Point probably wasn’t the Kid’s style. Ida’s best friend Tillie Keidel once shared a rumble seat with him on a trip from Fredericksburg to the dance hall in Gruene. Exhausted from fighting him off, she told Ida it seemed like the Kid had four hands. She rode with someone else on the trip home.

Ida also said the Kid was a mathematical genius, which might be true notwithstanding her propensity for embellishing Burke virtues. All three of the Burke siblings were smart as the dickens. The Kid’s son believes he was valedictorian of his high school class and received a scholarship offer. Bettye, the youngest sibling, was a member of Mensa. She once created a professional set of blueprints for a home she and her husband were building on the shore of Clear Lake. Ida, the eldest sibling, skipped two grades in elementary school, was valedictorian of her high school graduating class in Fredericksburg, and received full-ride scholarship offers from every major university in Texas.

I always thought she was exaggerating about those scholarships. Not so. After she died, I found them, seven in all, among her papers: University of Texas, Texas Technological College, SMU, Southwest Texas State Teacher’s College, Baylor, and TCU. Rice was tuition free, but they had an offer for her, too, because that’s where she went for her Freshman year. Then she switched to the University, where she was a Littlefield Dorm “beauty.”

October 1929 arrived, and she had to quit school to help support her family during the Great Depression. Gramps was a car salesman in Fredericksburg, and you can imagine how many people bought cars in the early 1930s. The family lived on the old Polo Grounds in San Antone for a while, eating so much peanut butter that Aunt Bettye swore off the stuff for life.

I don’t know what the Kid did in the 1930s, but he didn’t go to college, so far as I know. They would not have been able to afford it, even with a scholarship. I assume he also helped support the family during the Depression, as he was only 16 in 1930. He joined the Marines in time for World War II, probably after Pearl Harbor, when everyone enlisted. His tombstone identifies him as a First Lieutenant.[2] I don’t think he was ever stationed overseas. Mostly, he started getting married and kept it up his entire life. I have a tiny photograph of him in his Marine mess dress uniform when he was still a buck Sergeant, probably on his first wedding day. All told, he married four times. Looking at old pictures and remembering him, I can see why: he was an attractive man, with the standard issue navy blue Trice eyes and a charming grin. I thought he resembled JFK, another man with charisma.

Here’s a picture of the Kid with his sister Ida and her only child, who never learned to sit a horse worth a plug nickel:

Spoiler alert: at this point, the William Logan Burke stories take a dark turn. If you want a happy ending, sign off right now with the picture of Ida, Uncle Bill, and the little girl on the unhappy horse.

The last military record for him on Fold3 identifies him as a First Lieutenant on a 1946 muster roll. For as long as I knew him — beginning in the early 1950s — the Kid worked a blue collar union job in the Dow Chemical plant in Brazoria County. It was one of several plants which manufactured Agent Orange. He died in 1975, only 60 years old, consumed by what Ida called “more kinds of cancer than I ever heard of.” I will refrain from a rant about Agent Orange and just put some information in the footnote at the end of this sentence.[3]

Well, that is a downer of a way to end a story, but you can’t say you weren’t warned. I will demur re: writing about Little Bill, who may still be alive and who has a beautiful daughter out there somewhere. Fortunately, there is definitely another William Logan Burke, the family’s fifth. He is one of the sons of Little Bill’s brother Frank and a grandson of the Kid.

So far as I can tell from our emails, Frank’s nice family is sane, sober, and happy. It is also sizeable, so I’m rooting for a sixth William Logan Burke. Maybe he’ll become a Sheriff, and we will have come full circle.

See you on down the road.

Robin

[1] For some reason, Uncle Bill went by William Logan Burke Jr., notwithstanding that he was the third of that name in the line. He first son went by William Logan Burke III.

[2] Here is an image of the Kid’s tombstone.

[3] As early as 1962, the Monsanto Chemical Company reported that a dioxin in Agent Orange (TCDD) could be toxic. The President’s Science Advisory Committee reported the same to the Joint Chiefs of Staff that same year. As you probably know, Agent Orange was used as a defoliant in Vietnam. Many vets who served there have been diagnosed with cancer, but could rarely prove that Agent Orange was the cause. In 1991, the federal Agent Orange Act created a presumption that the chemical caused the cancer of anyone who served in Vietnam. That includes bladder cancer, chronic B-cell leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease, multiple myeloma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, prostate cancer, respiratory cancers including lung cancer, and some sarcomas.