They weren’t given a welcome back then. About 2.7 million Americans – almost 10% of their generation – served in Vietnam. Fifty-eight thousand names are on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall.

This isn’t a political rant, though. It’s just a story.

One of the American survivors, an Air Force pilot, left Vietnam on the so-called “Freedom Bird” on July 4, 1970. He landed in San Francisco and flew from there to Chicago’s O’Hare Field for a morning flight to Oklahoma City. Lacking cash for a hotel room, he stretched out on a bench at O’Hare. He slept soundly until a janitor working in the area dropped a metal bucket on the floor with a loud crash. The pilot was underneath the bench before he was fully awake.

Anyone living in a forward operating location was attuned to the sound of incoming mortar rounds. Those reflexes were basic survival skills.

This particular pilot was a forward air controller (“FAC”) in Vietnam, flying a plane designated 0-1E by the Air Force. It is a high-wing, tail-dragging airplane, less than 26’ long, able to take off and land in less than 600’. Crew: one person, protected by an armored plate under the pilot’s seat. Armament: eight smoke rockets, four under each wing. The sight for aiming the smoke rockets? A grease pencil mark on the cockpit windscreen to mark the horizon in level flight, installed by each pilot to his individual specifications – a function of the pilot’s height.

Here are a couple of pictures of the plane, one in the air and one on the Bien Hoa flight line at sunset.

These particular planes and the pilots who flew them, plus the supporting ground and radio crews, were part of the “Red Marker” unit. Red Marker FACs flew in close air support of the Vietnamese Airborne Division, elite Vietnamese paratroopers who went wherever in the country they were needed — the hot spots.

The O-1E FACs flew at about 1,500’, directing air strikes and occasionally ground artillery fire. That means the FAC would locate a target, call in a flight of fighter aircraft, make a low pass to fire a smoke rocket to mark the target, then clear each fighter to bomb with the characteristic radio call, “you’re cleared in hot … hit my smoke!”

The Vietnamese Airborne called the FACs “angels in the air.”

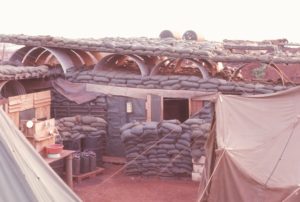

The ground living quarters for FACs at forward location bases were well-fortified. Here is an example.

The Song Be residents did not lack for a sense of humor …

And the Red Markers did not lack for pride.

The pilot who returned to U.S. soil on July 4, 1970 wrote a book about the Red Markers. His radio call sign was “Red Marker 18.” He only included a couple of his own stories in the book, because he didn’t want it to be “a personal memoir.” The following is a small supplement.

The propeller story

A so-called “tail-dragging” airplane (see above photos) has its third gear under the tail, as opposed to a tricycle gear plane, which has its third gear under its nose. Consequently, when a tail-dragger is on the ground, the pilot’s line of sight is slightly elevated – he cannot see the ground immediately in front of him.

If a pilot were in a hurry to refuel, reload rockets, and turn around for the next mission, and had been flying 2 or 3 flights a day for some time and was exhausted, he might take a short cut through a small ditch running alongside the runway. If there happened to be a metal runway marker between the runway and the ditch, he wouldn’t have been able to see it. This might be the result to the runway marker and the propeller …

By the way, that crummy piece of asphalt you see behind the runway marker? That’s the runway.

The night landing story

The longest day Red Marker 18 had was 11 hours flight time on three separate missions. Long days were common, especially during the Cambodian incursion. One evening, he didn’t get back to his home field until after dark. Runway lights in forward operating locations weren’t standard domestic airport issue. Instead, “runway lights” were what you would call smudge pots — bulbous metal pots with sand in the bottom, filled with diesel fuel and then lit. The duty for lighting the pots rotated among crews. It was apparently not popular duty: it may have interfered with beer call.

Red Marker 18 returned to Phouc Vinh one night, low on fuel. The pots weren’t lit, and he didn’t have enough fuel to land at an alternate field. His Red Marker radio control was unable to round up a crew to light the pots, so he took his jeep to the beginning of the runway and parked there with his headlights on. (Not a small heroic feat itself.)

When the 0-1E passed over the jeep and flared for landing, the pilot couldn’t see the runway ahead in the dark. So the jeep chased the plane all the way down the runway, illuminating it for the airplane with its headlights.

The mountain landing story

The 0-1E’s smoke rockets weren’t “armed,” i.e., live, while the airplane was on the ground, for obvious reasons. Before a flight, a crew chief loaded each rocket into a firing tube, four under each wing. Each tube had a safety pin at the rear which prevented an electrical connection needed to fire the rocket. Each pin had a red ribbon attached. Before the FAC took off, the crew chief pulled the pins and handed the ribbons to the pilot through the plane’s window, assuring the pilot that his rockets were ready to fire.

Unfortunately, Red Marker 18 and his crew chief each apparently had a bad day at the same time. About halfway to a pre-designated target area, he realized that his smoke rockets were not armed. The pins were still in, red streamers flying in the breeze. He had three choices. He could return to base to remove the pins, although he would then miss a scheduled rendezvous with a flight of fighters. That would effectively cancel the mission. Alternatively, he could mark the target for the fighters by throwing smoke grenades out of the airplane’s window. (I am not making this up). Of course, the fighter pilots would see the red ribbons, and he would never hear the end of jokes at his expense. His third alternative was to salvage the mission (and his reputation) by doing something which, in retrospect, was really, really ill-advised.

He landed on an abandoned air strip on a mountaintop. In the middle of the jungle in Vietnam. In the middle of the jungle in Vietnam. Alone, for heaven’s sake. He got out of his plane to pull the pins, but did not turn the engine off for fear that it might not restart — possibly the only sensible thing he did that day. This created a problem, because the brakes didn’t prevent the plane from creeping forward. Red Marker 18 had to hold on to the plane while removing the pins on each side of the aircraft.

When Red Marker 18 returned from that day’s mission, he handed the ribbons to the crew chief. No words were exchanged.

There are many more stories, of course. Every person who served in Vietnam, or any other war, has stories to tell.

If you by any chance meet a grizzled old Vietnam vet, please extend your hand and offer the appropriate greeting: welcome home, sir, and thank you for your service.

Here is a picture of Red Marker 18 with his airplane. I am grateful to have him home every day.

Happy 52nd anniversary, June 7, 2019.

See you on down the road.

Robin

In memoriam … Capt. Samuel L. James, USAFA 1967; Lt. Thomas L. Lubbers; Lt. Kennard F. Svanoe, USAFA 1967; Capt. Douglass T. Wheless, USMA 1968.