©Robin Rankin Willis May 2017

First, a disclaimer. This is a very long article because (1) there are nine children to discuss, (2) there are some nice stories about the family, two pictures, and partial transcriptions of two 1888 letters, and (3) I have religiously provided evidence in a mind-boggling plethora of footnotes. The extensive proof is included because several people have told me they really like to see it, and we aim to please.

OK, you’ve been warned. On to the article …

My husband Gary calls our favorite family history research tool the “follow the land” theory of genealogy, since family relationships can often be identified in land transactions. Proving the children of Lyddal Bacon Estes (hereafter, “LBE”) and his wife “Nancy” Ann Allen Winn[1] is a case study in that approach. The identities of all but one of the children who survived LBE are conclusively proved by Tishomingo County, Mississippi deed records. And that lone holdout is Lyddal Bacon Estes (Jr.), about whom there can be little doubt.

As a bonus, the deed records also paint a charming picture of the Estes family.

LBE’s land is our starting point. Tishomingo probate and deed records identify the Estes tracts, about 800 acres in all, as follows:[2]

- Northeast Quarter of Section 30, Township 2 South, Range 7 East;

- Northwest Quarter of Section 13, Township 2 South, Range 6 East;

- Southwest Quarter of Section 12, Township 2 South, Range 6 East;

- Southeast Quarter of Section 12, Township 2 South, Range 6 East; and

- Northeast Quarter of Section 12, Township 2 South, Range 6 East.[3]

LBE died intestate between January 1, 1845, when he performed a marriage as a Tishomingo J.P., and March 3, 1845, when his widow Nancy and Benjamin Henderson Estes obtained a bond as administrators of his estate.[4]

For almost a decade after he died, LBE’s 800 acres – which eventually sold for more than $4,000 – remained in the family, rather than being liquidated or partitioned. That is highly unusual. LBE had nine surviving children, including three married daughters. Any heir (or son-in-law) had the right to petition the court for either a sale of the estate’s land or a partition. As a result, the land of an intestate – i.e., someone who died without a will devising land to someone specific – was usually either sold or partitioned fairly promptly.

That didn’t happen in this family. Nancy and two of her sons, LBE Jr. (age 24), and Allen (18) were still living on family land in 1850, five years after LBE died.[5] That was apparently fine with the extended family, which seems downright loving. At minimum, it was generous. There is no right of usufruct in the English common law, so there was no legal requirement to let Nancy and the unmarried children remain in their home.

Moreover, in 1852, LBE Jr. married.[6] By 1854, the youngest son – Allen, who was born about 1832-33 – had just became an adult.[7] Also in 1854, Nancy and B. H. Estes petitioned the court for permission to sell the land in order to distribute the proceeds to the heirs.[8] The timing of that petition was surely not accidental. It suggests that the Estes family agreed after LBE died to keep the land together, with Nancy and minor children continuing to reside in the home place until all the children were grown.

The sweet family story doesn’t end there. At the 1854 public auction, LBE Jr. bought the entire 800 acres for $4,392, roughly $5.50/acre, a premium price.[9] Mind you, there is no way LBE Jr. had that much cash, or anticipated having that much cash in the immediate future. He was a farmer, and claimed only $1,400 in both real and personal property in 1860.[10]

A reasonable bet is that the family agreed LBE Jr. would bid on their behalf at the public auction, and then divide up the land later. For the cynical among us, the court records reveal that attendees at the auction included “several of the next of kin … as well as divers other persons.”[11] The court allowed the land to be sold on twelve months’ credit, so LBE Jr. didn’t have to fork over cash at the auction. Instead, he posted a bond, bought it on credit, and sold it in pieces to (1) Benjamin Henderson Estes (320 acres for $2,160 in August 1854, about $6.75/acre),[12] (2) Martha Swain (160 acres for $472 in August 1854, $2.95/acre),[13] (3) Riley Myers (160 acres for $1,400 in November 1856, $8.75/acre),[14] and (4) Nancy and Allen W. Estes (176 acres for $882 in January 1857, a bit over $5 per acre).[15]

Those deeds, of course, don’t prove that any of the parties were children of LBE and Nancy. For proof, we will have to look at each child. Here they are, in what I believe is birth order.

Benjamin Henderson Estes, b. Lunenburg, VA, 12 Dec 1815, d. 6 Jan 1897, buried in McLennan Co., TX.[16]

Benjamin H. Estes used his middle name in most records. Out of respect and affection, we will do the same. Henderson is proved as an heir of LBE and Nancy by a Tishomingo County quitclaim deed dated 15 Jun 1872. Henderson conveyed to Lyddal B. Estes (Jr.) any interest Henderson had in the northwest quarter of Section 13, Township 2, Range 6 East in Tishomingo, “which said claim and interest [Henderson] has by reason of being an heir and distributee of L. B. Estes, deceased, and Nancy A. Estes, deceased, the widow of said L. B. Estes.”[17] To be an heir at law of an intestate who had children, one had to be a child (or grandchild whose Estes parent had died). Since Henderson was too old to be LBE’s grandchild, he was necessarily a son.

Every census in which Henderson appeared from 1850 through 1880 identified him as having been born in Virginia, alone among LBE and Nancy’s children.[18] His birth in December 1815 in Virginia clearly marks him as the eldest child, since LBE and Nancy were married in March, 1814 in Lunenburg County, VA.[19] LBE made his last appearance in the Lunenburg records on March 22, 1816 on a personal property tax list as Lidwell [sic] B. Estes — so LBE and Nancy were still living in Lunenburg when Henderson was born.[20]

Henderson was involved in Tishomingo public life. He was a Justice of the Peace, a Constable, and a school board trustee.[21] He was apparently a family caretaker, serving as co-administrator of LBE’s estate and as sole administrator of a Winn cousin’s estate.[22] In October 1839, he married Mary A. Ducse, about whom I know nothing.[23]

Although he was 45 when war broke out, Henderson was a Captain in the 11th Mississippi Cavalry, Company A (aka Ham’s Cavalry).[24] LBE Jr. and Allen W. Estes were also officers in that unit, which I suspect (but cannot prove) Henderson helped organize. He was proud of his service, notwithstanding that he was on the wrong side of history and justice. And decency. His tombstone states his rank and unit.[25]

After the War, Henderson and his family moved to McLennan County, Texas, near Waco. He still identified himself as a farmer.[26] He didn’t own any land that I could find, so he must have been farming with family, probably his son Lyddal Bacon Estes (LBE the 3rd). In 1880, he and LBE 3rd were both listed in the Brown County census, several counties west of McLellan.[27]

Henderson returned to McLennan County one last time, as he and his wife Mary are both buried in the Robinson Cemetery there. The identity of their children is disputed. I identify them as follows from census records, their migration from Tishomingo to McLennan, and burial of Mary and Nancy in the Robinson Cemetery.

- Mary A. Rebecca Estes, b. 19 Oct 1849, Tishomingo, d. 12 Jul 1909, McLennan Co., TX. Married William Griffin 18 Sep 1871, McLennan Co.

- Lyddal Bacon (“Bake”) Estes, b. about 1855, Tishomingo, d. 22 Mar 1918, Grant Co., NM. Married Martha (“Mattie”) Brandon 15 Nov 1885, McLennan Co.

- Nancy California (“Callie”) Estes, b. 29 Oct 1856, Tishomingo, d. 12 Nov. 1937, McLennan Co. Husband Benjamin P. Hill.

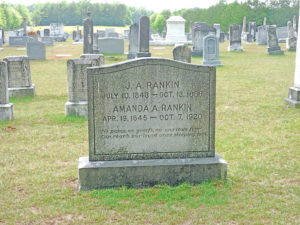

Mary F. (undoubtedly Frances) Estes Rankin, b. AL 1817-18, d. after 1888, Cleveland Co., AR.

Mary is my ancestress, although I don’t know much about her. She was LBE and Nancy’s eldest daughter. Her year and state of birth vary in the censuses, but she was likely born in 1817-18[28] in Madison County, Alabama.[29] About 1836, she married Samuel Rankin in the area of the Chickasaw Nation that became Tishomingo County in the northeast corner of Mississippi. The Rankins moved to Jefferson County, Arkansas in late 1848 or 1849.[30]

Another quitclaim deed proves that Mary F. Rankin was a daughter of LBE and Nancy. It was dated 31 August 1872, from Mary Rankin as grantor to L. B. Estes (Jr.), grantee. The deed did not state that Mary’s claim to the land conveyed arose via heirship, as did Henderson’s. The description of the land is all the evidence we need, however. Specifically, Mary conveyed her right to land in the northwest quarter of Section 13, Township 2, Range 6.[31] The only way Mary had a claim to that tract was as an heir of LBE and Nancy. Like Henderson, she was too old to be a granddaughter.

I have a portrait of Mary with her grandson John Marvin Rankin by her side. My grandmother, John Marvin’s wife, identified them in writing on the back of the portrait as “JM” and “Mary,” so there isn’t any doubt about her identity. It was taken about 1878, when she was about sixty – but she looks 80 (although perhaps I am underestimating the benefits of sunscreen, moisturizers, good nutrition, and birth control). She is not attractive, to understate the matter wildly. She has large ears, accentuated by the fact that her hair is parted in the center and pulled back severely in a bun (two of my uncles had the misfortune to inherit those ears). It is difficult to imagine that she ever smiled, looking at her downturned mouth and the lines around it.

Here is the photo.

It’s easy to sympathize with Mary. Her husband Samuel was almost two decades her senior and an incorrigible character, although that’s another story. She had ten children who survived her; the first eight arrived less than two years apart like clockwork. There were still seven minors at home when Samuel died in 1861 or 1862, and her youngest child was born about the time he died or soon thereafter.[32] Mary couldn’t read or write, although her siblings for whom I could find that information were literate.[33] Four of her sons fought in the Civil War, two on each side. That’s another story, too. The family was apparently not poor, but they didn’t have much and the children didn’t inherit anything, judging from their subsequent economic situations. Mary undoubtedly worked from sunrise until past sunset all her life.

In short, Mary qualifies as what we Texans call “rode hard and put up wet,” and my heart goes out to her. Ten children survived her:

- Richard Bacon Rankin, b. May 1837, Tishomingo, d. Mar 1930, Cleveland Co., AR. Married three times. He has a military tombstone inscribed Co. H., 5 Kansas Cavalry, a Union unit.

- William Henderson Rankin, b. Nov 1839, Tishomingo, d. Sep 1910, Little Rock, Pulaski Co., AR. Married Eliza Jane Law, 1858, Drew Co., AR. Private, Owen’s Battalion, Arkansas Light Artillery, CSA, enlisted at Monticello, Drew Co., in Feb 1862.

- Joseph S. Rankin, b. Aug 1841, Tishomingo, d. Arkansas? Married Nancy J. White.

- John Allen Rankin, my great-grandfather, b. Jul 1843, Tishomingo, d. Oct. 1888, Claiborne Par., LA. Married Amanda Adieanna Lindsey, July 1865, in Claiborne Parish. Private, 9th Arkansas Infantry, enlisted Jul 1861. Deserted October-November 1863, twenty-one months into his one year enlistment term after a disastrous battle for the CSA, a newly issued uniform, and several months’ back pay.

- Elisha Thompson Rankin, b. May 1845, Tishomingo, d. Apr 1911, Pike Co., AR. Married Martha Willie Daniel. Enlisted 1863, Private, 5th Kansas Cavalry, Union pension approved May 1898.

- James D. Rankin, b. Apr 1848, Tishomingo, d. Nov 1930, Drew Co., AR. Married Mary Allen “Mollie” Matthews, 1870.

- Mary Jane Rankin, b. 1850, Jefferson Co., AR, m. Nick Scott, 1875, Jefferson Co.

- Washington Marion Rankin (“Wash”), b. Mar 1852, Jefferson, AR, d. after 1920, probably Pulaski Co., AR. Married Victoria A. Hall; divorced.

- Napoleon Bonaparte Rankin (“Pole”), b. Jul 1855, Jefferson, AR, d. after 1928, probably Dallas Co., TX. Married #1 Ivy Lee Brooks, #2 Alice Austin.

- Frances Elizabeth Rankin (“Lizzie”), b. Feb 1862, Jefferson, AR, d. 1919, Grant Co., AR. Married Robert Bearden, Dec 1877, Cleveland Co., AR. Had 11 children; widowed at age 40.[34]

Martha Ann Estes Swain (b. Madison Co., AL, Sep. 1819 – d. 2 Mar 1905, McLennan Co., TX).

Martha was seemingly as sunny and upbeat as her sister Mary appeared to be dour. Martha was still describing herself as a farmer at age eighty.[35] I have copies of transcriptions of two letters Martha wrote to Mary in 1888, and they are charming, chatty, gossippy, kvetchy, and full of love for the extended family group she called “the connection.” (See excerpts below in the discussion of Lucretia Estes Derryberry).

Her 1905 obituary is worth quoting in full:[36] “Mrs. Martha Swain died on March 2, at the home of her son L. B. Swain, at Golinda, at the advanced age of 87 years. She died of pneumonia and was sick only a few days. She leaves two children, one son, L. B. Swain, of Golinda, and Mrs. J. N. Strahan, of the Hillside community. Also a large number of grand and great-grand children to mourn her demise. The entire community extends sympathy to the mourning relatives and friends and also feels the loss of a noble woman. We could write at length of the good deeds of this good woman, as it was our privilege to know her for over thirty years. –Eli Gib.”

She had nine children and outlived all but two of them, which strikes me as the worst thing that can befall a human being.[37] Nevertheless, she persisted. I found no marriage record for Martha and Wilson Swain, but other records suggest they were married by the mid-1830s.[38] Wilson died about 1849, because Martha was a head of household in 1850 with the youngest child in the family only one year old.[39]

Martha bought one of the Estes family tracts from her brother LBE Jr. in 1854, which she sold in two pieces in 1871.[40] Also in 1871, she executed a quitclaim deed to LBE Jr. for – you can undoubtedly guess this by now – the northwest quarter of Section 13, Township 2, Range 6 east.[41] By 1871, Martha was clearly about to move to Texas.

Four of Martha’s nine children apparently did not live long enough to be named in the 1850 census. She also had two children – Armistead and Josephine – about whom I found nothing in the records except census listings in 1850 and 1860. Her other three children moved to Texas with Martha, although only two of those outlived her. Here are the children who evidently survived to adulthood:

- Nancy J. Swain, b. 1837-38, Tishomingo. She married M. W. Oldham in McLennan Co., TX, 25 May 1882. She has a Robinson Cemetery joint tombstone with John Neil Strahan on which her date of birth is shown as “abt 1837” and her name as “Nancy Jane Swain Oldham,” death in May 1912.[42] John N. Strahan was obviously her second marriage, date unknown.

- Mary Ann Swain, b. about 1840, Tishomingo. She married J. N. Strahan in McLennan Co., 28 Feb 1872. I found no death or cemetery record, but she apparently died before May 1882, after which J. N. married her sister Nancy J. (who must by then have been the widow of M. W. Oldham).

- Lyddal Bacon (“Bud”) Swain, b. Dec. 1846, Tishomingo, d. Dec. 1923, McLennan Co. Confederate veteran. Wife Martha Ann Hill.

Martha Ann Estes Swain also features prominently in her sister Lucretia’s story, up next.

Lucretia Estes Derryberry (abt. 1822-23, Madison Co., AL, d. after 1888, probably in Little River, AR).

Lucretia (nicknamed “Cretia” or “Creasy,” as was her maternal grandmother, Lucretia Andrews Winn) and her husband Henderson D. B. Derryberry were married in January 1844 in Tishomingo.[43] In 1858, the couple executed a deed to her brother Henderson Estes, for $100, “all right, title, claim and interest” the Derryberrys had “as legatee of the estate of Lyddal B. Estes” in all of LBE’s land, described by section, township and range.[44]

Cretia and H.D.B. left Tishomingo shortly thereafter, moving first to Nacogdoches County, Texas, and then to Little River County, Arkansas. They appeared faithfully in the census records in 1850 (Tishomingo),[45] 1860 (Nacogdoches),[46] 1870, (Little River)[47] and 1880 (ditto).[48] I cannot find a death or cemetery record for Lucretia, but H.D.B. died in 1887 and is reportedly buried in the Campground Cemetery in Winthrop, Little River Co., AR.

Identifying their children is difficult because the names and years of birth vary from census to census, although I confess I haven’t looked at anything but census records. All of their children except for John were born in Tishomingo, and he was born in Arkansas. I’m confident about the names of only 5 children, although there were at least three more.

- Isaac Derryberry, b. 1844-45.

- Nancy Derryberry, b. 1846-48.

- Virginia Derryberry, b. 1848-49.

- Martha Caroline Derryberry, b. 1850-51.

- John Derryberry, b. 1858-59.

In between Martha and John were three sons born 1851-1857: Calvin, William and Gilbert (according to the 1860 census). Two of them had the middle (or first) name of Scott and Anderson, according to the 1870 census. I’m baffled, and haven’t sorted it out. If this is your line, please set me straight.

Here is some fun stuff: family gossip. By way of necessary background, Cretia and H.D.B. had a granddaughter Martha Derryberry, whose parents I have not identified. In 1880, Martha, age 9, was living with H.D.B. and Cretia. By 1887, H.D.B. was dead. Here, verbatim (including “xxx” where the transcriber couldn’t interpret the handwriting, as well as question marks) are excerpts from two 1888 letters Martha Estes Swain wrote to her sister Mary Estes Rankin. My comments/interpretations are in italics. Martha opens the first letter by demanding in no uncertain terms to know why the hell her sister hasn’t written, and then moves on to the gossip.

Excerpt from first letter, written to Mary when Martha was visiting Cretia in Little River

“April the 24 1888, Little River Co. Little River PO.

Well mi dear sister i will write you a few more lines to let you no how i am getting along i rote to you when i first came out here and i have not heard from you yet i would like to no what is the mater that you don’t rite we are all well at this time and i do hope that these few lines will find you all well and doing well well i am going to start home tomorrow morning Cxxxx [Cretia] and isac? [Isaac, eldest son of HDB and Cretia] will go to Texar kana and then we will part I hate to leave Cxxxxx [Cretia] for she xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx run away and married and now Cxxxxx will bea left alone and that is mity bad because she is to old to bea left alone … and write to Cxxxxx she wants to hear from you all mity bad well i will bring mi letter to close me and Cxxxxx send our love to all so good by for this time

M A Swaine to Mrs M A [sic] Rankin”

Summary and excerpt from second letter, after Martha has returned home from Little River, June 16th [1888]

Martha begins by thanking Mary for her letter and complaining about her rheumatism. She says she hasn’t seen Mary and Henderson since she came home, talks about crops, asks about Mary’s lost cows, and mentions some family, noting who has written to her and who has not: Lizzie (Mary’s youngest child), Mr. Strahan (an in-law, who is moving to Wilbarger Co., TX), Minnie (Bearden, a granddaughter of Mary’s), John (several possibilities), Judge (a son of Richard Bacon Rankin), Pole (Mary’s son), Wash (ditto), Aunt Jane and Dulo (I have no idea), and Joe Estes (Allen W. Estes’s only child, a nephew of Martha and Mary’s). Then Martha gets down to the nitty gritty with obvious relish.

“well Mary I will tell you something about my trip home i stayed with sister Creby [sic, Creasy or Cretia] til the 25th of April her and isac come with me to Tex arcance i taken the train at 11 in the morning I got at Waco at 12 20 at night. bud [Lyddle Bacon Swain, Martha’s son] met me there and we came 9? miles at brother henderson I stayed there until saturday morning and started home saturday morning and got caught in a big rain before I got to brother tonys? [Martha’s brother LBE Jr.] I hant been well since I got home the first day of may i never hated to leave anybody as bad as i did Cxxxx [Cretia] Martha [the granddaughter, married 8 Apr 1888] she run away and murried and left Cxxxx a lone i think she could do as well without her as with her although she was left a lone she was mighty disobedient to her grandma i am afraid she has done bad business in murring I got a letter dated the 15th of may and she [Cretia] said she was still liveing a lone and she said they was all well write soon and often and give me all the news a bout all of the connection be sure and come if you can I will bring my few lines to a close your sister until death

Martha Swain”

On that note, let’s leave Cretia, Martha, and Mary with a smile, and go see about the next Estes sibling. I wish I had known those three women.

John B. Estes (b. Madison Co., AL 1822-24, d. between 1872-1880, Nacogdoches Co., TX)

John B. Estes is a mystery because the records reveal very little about him. He wasn’t listed in the 1850 census, so far as I can find. Perhaps he was on the move. He had clearly arrived in Nacogdoches County by August 1851, when he married Avy Ann Summers there.[49] She was a widow, née Parish,[50] and had three children. John B. Estes was listed in the 1854 school census as their guardian, and he gave Alabama as his state of birth.[51]

The couple executed a deed dated 19 August 1853 conveying to LBE Jr. for $200 all “right, title, claim they may have as legatees of the estate of Liddal [sic] B. Estes, dec’d, late of Tishomingo,” to LBE’s land. Like the Derryberry deed, it included a description of LBE’s tracts by section, township and range, leaving no doubt that John B. was LBE’s son.[52]

John B. owned several tracts in Nacogdoches County. I have not delved into the county probate records to see if there was an estate administration, although there must have been in light of his land ownership. The census records reveal only one child, a daughter Nancy A. Estes, born about 1861. Nancy was listed in the 1870 census with John B. and Avy Ann and in 1880 with her mother, who was widowed by then.[53] Ancestry.com trees give John’s middle name as “Byron,” without citing any sources except other online family trees. I would love to hear from anyone having actual evidence about that name.

Lyddal Bacon Estes Jr. (b. McNairy Co., TN? 20 Sep 1826, d. McLennan Co., TX, 18 Apr 1903).

Ironically, LBE Jr. didn’t execute a deed reciting heirship, although I can’t imagine there could be any reasonable doubt about his parentage. The entire record of his land transactions among family members, and his unusual name, and the fact that he appeared in Nancy A. Estes’s household in 1850, constitute sufficient circumstantial evidence to establish him as a son of LBE and Nancy.

LBE Jr. was a Confederate veteran, a First Lieutenant in the same cavalry unit in which his brothers Henderson and Allen W. Estes served.[54] A county history identifies him as “Toney” Estes, as does one of Martha Swain’s letters excerpted above. Interesting nickname for a family of solidly British Isles heritage on both sides.

In 1852, LBE Jr. married Elvira Caroline Derryberry, a sister of H.D.B. Derryberry, in Tishomingo.[55] LBE Jr. was apparently the last of LBE and Nancy’s children to remain in Tishomingo – or Alcorn County, by the time he left. He last appeared as a resident there acknowledging a deed dated November 1876.[56] By March 1879, he was in McLennan County, where he executed what appears to have been his last deed to Mississippi land.[57]

LBE Jr. was a landowner in McLennan County and left some helpful estate administration records, including one identifying his children.[58] His widow Caroline applied for letters of survivorship on August 5, 1903, reciting that her husband died intestate in McLennan in April 1903 and giving his children’s ages and residences.

- Louisa Russell, 50, Hill County, TX.

- Harriet Wood, who predeceased LBE Jr., leaving 2 surviving children in Jones Co.

- F. (Margaret Frances) Garner, age 46, residing in McLennan Co.

- Mark L. Estes, 44, Jones Co., TX.

- Mattie Coyel, age 42, also a resident of McLennan.

- Emma? Moore, 34, resident of Bosque Co., TX.

- Florence Cooksey, 32, McLennan.

LBE Jr. was also kind enough to leave a picture of himself and Caroline that is widely available in family trees online. Here it is. He was clearly a snappy dresser, which might account for his nickname.

Alsadora Estes Byers, b. abt. 1828?, McNairy Co., TN, d. ???

Alsadora was named for her mother Nancy A. Winn Estes’s youngest sister, Alsadora Abraham Winn Looney, and that is the only interesting thing I know about her. Alsadora married Edward Byers in Tishomingo on September 16, 1845. In 1850, she and Edward were listed in the Tishomingo census with three children.[59] That census gives her age as 20, but earlier census records for LBE’s family, and her brother William’s likely birth year, suggest she was born a year or two earlier.

There is, of course, the inevitable deed proving that Alsadora Estes Byers was a daughter of LBE and Nancy. On 14 March 1847, Edward and Alsadora conveyed to her brother Henderson all of the “right, title, claim and interest they have as a legatee of the estate of Lyddal B. Estes” in LBE’s land, all tracts described by section, township and range.[60] No doubt about that parentage. I would almost have deemed her proved just on the strength of that highly unusual given name and the fact that LBE’s was the only Estes family in Tishomingo in the mid-1800s.

William P. Estes, b. abt 1830, McNairy Co., TN?, d. unknown (San Francisco Co., CA?)

William P. was probably born about 1830, because he first appeared as a taxable on the Tishomingo tax rolls in 1848. He is listed on the tax rolls again in 1849, but he is not in the 1850 census in Tishomingo. I found only two other records for him. One was a general power of attorney he granted to Henderson in 1853 which identified him as a resident of San Francisco County, California.[61] Second, there was the 1872 deed reciting that William, Alsadora Byers, Lucretia Derryberry and Henderson Estes were heirs and legatees of LBE, from B. H. Estes of McLennan Co., TX to Lyddall B. Estes of Alcorn Co., Mississippi.[62] Specifically, Henderson quitclaimed for $100 any interest he had in the northwest Quarter of Section 13 Township 2 Range 6 East, “which … the party of the first part having previously bought and had conveyed to him the interest of Lucretia Derryberry of Elsidora Byers and of William P. Estes thereafter other heirs and distributees of the said L. B. Estes and Nancy A. Estes, dec’d.”

Given the timing of his departure in about 1850 and his destination, one might speculate that William was bitten by the gold rush bug. Please let me know if you have any info on him.

Allen W. Estes, b. 1832, TN, d. 29 July 1864, CSA Hospital in Atlanta, GA

Allen W. (and my money is on Allen Winn), LBE and Nancy’s youngest child, died at the Battle of Ezra Church. In 1864, that was west of Atlanta. Now it is just off I-20 at MLK Boulevard, well inside the city limits. He was a Captain in his cavalry unit, the same one in which his brother LBE Jr. and Henderson served. They fought “dismounted” at Ezra’s church, meaning as infantry. They were commanded by an incompetent general who had his troops repeatedly charge a well-fortified position on higher ground against orders. The general was ordered to contain the Union troops, not advance.

The same foolish general – Steven Dill Lee, no relation to Robert E.– commanded my great-grandfather John Allen Rankin’s unit at the Battle of Champion Hill near Vicksburg with similar incompetence, so I have a real grudge against him. My husband and I wrote an article about the three Confederate Estes brothers in Ham’s Cavalry, which you can find here. Gary, a graduate of the Air Force Academy and an amateur military historian and tactician (and grizzled Vietnam vet), provided the battle information. There is also an article about John Allen’s war story on this website, with Gary again contributing military savvy.

I just hope Nancy had already died before she learned about Allen’s death. He was, I can guarantee, still her baby at 32.

The only other thing that stands out about Allen is the puzzle he created by failing to leave a deed proving his parents’ identity. Other records provide compelling circumstantial evidence, although not conclusive proof, that Allen W. was a son of LBE and Nancy. The deed records come through for us again, though. First, here are the census and marriage records, which also identify Allen’s only child:

- Allen Estes, 18, was living with Nancy A. Estes in the 1850 census.

- In 1859, Allen married Josephine Jobe, and Allen W. and Josephine Estes were living with Nancy in 1860.

- In 1868, Josephine Estes married G. L. (Grimmage) Leggett.

- In the 1880 census, Jos. Ester [sic] was listed in the household of Grim Leggette along with his wife Josephine. Joseph, 18, was identified as Leggette’s stepson, and thus a son of Allen W. and Josephine Jobe Estes Leggett.

Of course, that still isn’t conclusive proof that Allen W. was a son of LBE and Nancy: he could have been a nephew. We need the deed records. They get a bit esoteric …

Back in 1857, Allen W. and Nancy bought one of LBE’s tracts – and this one is key: the northwest quarter of Section 13, Township 2, Range 6 East, the only tract in Section 13. As a matter of law, Nancy (who was a single woman in 1857), could actually own property in her own name. Imagine that! She and Allen each owned an undivided interest in the tract. I never found a will or estate administration for either Nancy or Allen. Both probably died intestate.

Under the law of intestate descent and distribution, Nancy’s half of the tract would have descended to Nancy’s heirs — her surviving children, plus any children of a deceased child. Allen’s half of the tract would have descended to his sole heir, Joseph. By 1872, LBE Jr. owned all the children’s claims to that tract except for Allen’s: (1) LBE Jr. had purchased all of John B. Estes’s interest in LBE’s land; (2) Henderson had purchased all of William, Alsadora Byer’s, and Lucretia Derryberry’s interest in all of LBE’s land, which he quitclaimed to LBE Jr.; and (3) LBE had quitclaim deeds to that specific tract from Henderson, Martha and Mary.

In short, the only surviving heirs who had claims to any part of Allen and Nancy’s Section 13 tract were LBE Jr. and Joseph Estes. You’ve got to appreciate the English common law obsession with orderly land transfers and records. And being in a county that William Tecumseh Sherman missed.

LBE Jr. asked the court to partition the tract between him and Joseph Estes. A commission did just that, laying out 9/16ths of the tract to LBE Jr., and 7/16ths to Joseph. I have no idea how they came up with those fractions, except that one of the partitioned tracts must have had improvements that the other lacked.

And, my friends, that is it. Whew! I congratulate anyone who made it through this entire piece. The secret word is “footnotes.” Put it in a comment on this article and I will buy you a Starbucks coffee. Or send you a gift certificate for same.

[1] Either “Nancy” or “Ann” was a nickname, probably Nancy. She appeared in the Lunenburg Co., VA records as Ann Allen Winn (Lunenburg Will Book 6: 204, FHL Film 0,032,381, her father Benjamin Winn’s will), Nancy Allen Winn (Lunenburg Guardian Accounts 1798 – 1810, FHL Film 0,032,419, at p. 136), and Nancy A. Winn (Emma R. Matheny and Helen K. Yates, Marriages of Lunenburg County Virginia 1746 – 1853 (Richmond: 1967, reprinted by Genealogical Publishing Co., Baltimore, 1979), Nancy’s marriage to LBE).

[2] Tishomingo Probate Records Vol. M: 484, court order of 14 Mar 1854 to sell the land of Lyddal B. Estes, identifying the tracts by section, township and range; id. at 438, court order regarding notice and citation; Tishomingo Deed Book R: 15, FHL Film 0,895,878, deed of 30 May 1854 conveying the land and identifying the tracts by section, township and range.

[3] There is a minor question about this tract. At least four Tishomingo court and deed records identify it as the northeast quarter. Online BLM records identify it as the northwest quarter.

[4] See Irene Barnes, Marriages of Old Tishomingo County, Mississippi, Volume I, 1837 – 1859 (Iuka, MS: 1978), LBE presided as J.P. at a marriage on 1 January 1845; FHL Film 0,895,897, Tishomingo Probate Records Vol. C: 391, 3 Mar 1845 bond of Benjamin H. Estes and Nancy A. Estes as administrators of Lyddal B. Estes.

[5] 1850 U.S. census, Tishomingo, Nancy Estes, 62, b. VA, with Bacon Estes, 24, b. TN, and Allen Estes, 18, b. TN; see FHL Film 0,895,878, Tishomingo Deed Book R: 15, deed of 30 May 1854 reciting that the 1854 auction of the land was held at LBE’s house.

[6] Thomas Proctor Hughes and Jewel B. Standefer, Tishomingo County, Mississippi Marriage Bonds and Ministers’ Returns, January 1842-February 1861 (1973), 11 Feb 1852 marriage of L. B. Esters [sic] & Emaline C. C. Derryberry.

[7] 1850 U.S. census, Tishomingo, Allen Estes, age 18 (born about 1832); 1860 U.S. census, Tishomingo, Allen W. Estes, age 27 (born about 1833). Allen was living in Nancy’s household in 1860 along with his wife Josephine (Jobe) Estes. See Hughes and Standefer, Tishomingo County, Mississippi Marriage Bonds, marriage of W. A. Estes [sic, should be A. W.] and Josephine Jobe, 13 Oct 1859.

[8] I could not find the administrators’ petition among the county records, but the court order to sell the land references it. Tishomingo Probate Records Vol. M: 484, court order of 14 Mar 1854.

[9] FHL Film 0,895,878, Tishomingo Deed Book R: 15, deed of 30 May 1854 reciting inter alia the following: B. H. Estes and Nancy Estes, administrators of L. B. Estes, dec’d, to Lyddal B. Estes Jr. of Tishomingo … whereas the probate court on 2nd Monday in March 1854 ordered to sell on 12 months’ credit all the land of dec’d containing 800 acres … on a portion of said land L. B. Estes resided at his death and had thereon a dwelling house, stables and other appurtenances. Notice of the time and place of sale was given in a newspaper and by posting copies of the notice at public places. The sale was held between 12 noon and 5 p.m. at LBE’s residence on May 1, 1854. The highest bidder was Lyddal B. Estes Jr.: $4,392.

[10] 1860 U.S. census, Lyddal Estes, 33, farmer, $1000 realty, $400 personal property, b. TN, Caroline Estes, 23, b. TN, Louisa Estes, 6, b. MS, Harriet Estes, 3, b. MS, and Marcus Estes, 2, b. MS.

[11] Tishomingo Probate Book 5: 255–56 (original viewed at the chancery court in Iuka, MS, administrators’ report of the sale).

[12] FHL Film 0,895,878, Tishomingo Deed Book R: 19, deed from L. B. Estes and wife to B. H. Estes.

[13] FHL Film 0,895,878, Tishomingo Deed Book R: 18, deed from L. B. Estes and wife to Martha Swain.

[14] FHL Film 0,895,881, Tishomingo Deed Book U: 570, deed from L. B. Estes and wife to Riley Myers. I’m not sure what Riley’s relationship to the Estes family might have been, if any.

[15] FHL Film 0,895,881, Tishomingo Deed Book U: 155, deed from L. B. Estes and wife to A. W. Estes and Nancy A. Estes.

[16] Central Texas Genealogical Society, Inc., McLennan County, Texas Cemetery Records, Volume II (Waco, TX: 1973), tombstone for B. H. Estes in the Robinson Cemetery.

[17] FHL Film 0,895,389, Tishomingo Deed Book 2: 590.

[18] 1850 U.S. census, Tishomingo, B. H. Estes, 35, farmer, b. VA, with Mary Estes, 32, b. TN, two children sometimes identified as Henderson and Mary’s, and their daughter Mary, age 1; 1860 U.S. census, Tishomingo, Benj. H. Estes, 43, farmer, b. VA, Mary Estes, 41, Mary Estes, 11, Siddle (sic, Lyddal) Estes, 5, and Nancy Estes, 3 (plus Thadeus Gossitt, 15, who was also listed in this family in 1850); 1870 U.S. census, McLennan Co., TX, Waco P.O., Benjamin Estes, 55, farmer, b. VA, Mary Estes, 51, Rebecca Estes, 21, MS, Bacon Estes, 15, MS, and California Estes, 14, MS; 1880 U.S. census, Brown Co., TX, Benjamin Estes, 64, b. VA, and wife Mary Estes, 60, TN.

[19]Henderson’s stated year of birth varies from 1815 to 1817 in the census records, but his tombstone says 1815. https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=7096040&ref=acom; see also Matheny and Yates, Marriages of Lunenburg County, Virginia, Lyddal B. Estes of Lunenburg and Nancy A. Winn, married 10 March 1814.

[20] Clayton Library microfilm #239, Lunenburg County, Virginia Personal Property Tax Records, 1805 – 1835, 1816 personal property tax list, Upper District of Lunenburg, Lidwell [sic] B. Estes, one taxable poll, visited on 22 March 1816.

[21] Fan A. Cockran, History of Old Tishomingo County, Mississippi Territory (Oklahoma City: Barnhart Letter Shop, 1969).

[22] Tishomingo Probate Records Vol. C: 606, FHL Film 0,895,897, petition of Benjamin Estes for administration of the estate of John Winn.

[23] Cockran, History of Old Tishomingo County.

[24] Id.

[25] See note 19, link to an image of his tombstone.

[26] See note 18.

[27] 1880 U.S. census, Brown Co., TX, Benjamin Estes, p. 443, dwelling. 90, age 64, b. VA, parents b. VA, Mary A. Estes, wife, age 60, b. TN, parents b. VA; adjacent listing in dwelling 91, Luddell [sic] Estes, 25, b. MS, father b. VA, mother b. TN, Rebecca Estes, wife, 19, and Newton B. Estes, b. Sep 1879, TX.

[28] 1850 U.S. census, Jefferson Co., AR, household of Samuel Rankin, Mary Rankin, 31, b. MS; 1860 U.S. census, Jefferson Co., household of Samuel Rankin, Mary F. Rankin, 42, b. AL; 1870 U.S. census, Jefferson Co., household of Mary F. Rankin, 50, b. AL; 1880 U.S. census, Dorsey Co., AR, household of Robbert Bearden, Mary F. Rankin, mother-in-law, 63, b. AL.

[29] I have not found LBE and Nancy in the Madison County records, but it is clear from the extended Winn family in McNairy Co., TN and Tishomingo that the couple migrated with Nancy Winn Estes’s family of origin. Nancy’s mother, Lucretia Andrews Winn, definitely migrated from Lunenburg to Madison Co., where she and several of her children appeared in the records.

[30] See 1860 U.S. census, Jefferson Co., AR, household of Samuel Rankin, indicating that James Rankin was born in Mississippi about 1848 and the next child, Mary Rankin, was born in Arkansas about 1850; Tishomingo Deed Book M: 219, FHL Film 0,895875, deed dated 18 Nov 1848, Samuel and Mary Rankin acknowledged it the same day. It was their last appearance in person in Tishomingo.

[31] Tishomingo Deed Book 2: 588, FHL Film 0,895,389.

[32] In the 1861 tax list for Jefferson Co., AR (which I viewed at the county courthouse in Rison, AR), Samuel Rankin was taxed on 280 acres. In 1862 and 1865, his son Joseph S. Rankin was taxed on that acreage, although there was no deed conveying it. Samuel and Mary’s youngest child, Frances Elizabeth (“Lizzie”), was born in Feb. 1862, see 1900 U.S. census, Cleveland Co., AR, household of Robbert Bearden.

[33] 1870 U.S. census, Jefferson Co., Mary F. Rankin, cannot read or write. Compare the 1870 the census for LBE Jr. (Alcorn Co., MS), Henderson Estes (McLennan Co., TX), John Esthers (sic, Nacogdoches Co., TX), Lucretia Derryberry (Little River Co., AR, where the census taker marked the literacy columns exactly backward); see also 1900 census, Martha Swain (McLennan Co.).

[34] https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=7127018&ref=acom

[35] 1900 U.S. census, McLennan Co., TX, Martha Swain, b. Sep 1819, widow, age 80, farmer (!!!), has had nine children, 2 living.

[36] Waco Weekly Tribune, Waco, Texas, Saturday, March 11, 1905, p. 11.

[37] Id.; see also note 35.

[38] 1837 Mississippi State census, Tishomingo, Wilson Swain, listing #65 (next to Samuel Rankin), 1 male 18 < 21, 1 female > 16, and 2 females < 16; 1840 U.S. census, Tishomingo, household of Wilson Swain, 1 male, 20 < 30, 1 female, 15 < 20, and 2 females < 5; Tishomingo Deed Book S: 340, deed dated 1 Jan 1846 from Wilson Swain to Seaborn Jones signed by Wilson Swain and Martha Ann Swain.

[39] 1850 census, Tishomingo, household adjacent to Nancy A. Estes, Martha Swain, 30, b. AL, with Nancy Swain, 13, Mary Swain, 10, Bacon Swain, 4, Armistead Swain, 2, and Josephine Swain, 1, all children b. MS; 1860 census, Tishomingo, household adjacent to LBE Jr., Martha A. Swain, 42, farmer, b. TN, with Nancy J. Swain, 22, Mary A. Swain, 20, Bacon Swain, 14, Annista (sic, Armistead, male), 12, and Martha, 11, all children b. MS; 1870 census, Alcorn Co., Martha Swain, 50, farmer, b. TN, with Nancy Swain, 30, MS, Mary Swain, 27, MS, Lucius? Swain, should be Lyddal Bacon, 25, MS, Martha Swain, 25, MS, and Alice Swain, 4 (not Martha’s child).

[40] Tishomingo Deed Book R: 18, FHL Film 0,095,878, deed from L. B. Estes and wife Elvira C. C. Estes to Martha Swain, 160 acres for $472; Alcorn Deed Book AA: 563; Alcorn Deed Book 1: 176 and 184.

[41] Alcorn Co. Deed Book 2: 436, FHL Film 0,895,389, deed dated 11 Dec 1871, quitclaim for $1.

[42] https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=35256937&PIpi=16426853.

[43] Barnes, Marriages of Old Tishomingo County, Mississippi or Tishomingo County Mississippi Marriage records 1837 – 1900 (Ripley, MS: Old Timer Press). I am not sure which abstract I used.

[44] Tishomingo Deed Book M: 188, FHL Film 0,895,875, deed dated 23 Sep 1858 from the Derryberrys to Henderson Estes conveying all their interest in LBE’s land.

[45] 1850 U.S. census, Tishomingo, H. B. Derryberry, 28, farmer, b. TN, Lucretia Derryberry, 29, b. AL, Isaac Derryberry, 6, Nancy Derryberry, 4, Virginia Derryberry, 2, and Martha Derryberry, 6 months, all children b. MS.

[46] 1860 U.S. census, Nacogdoches Co., TX, Henderson Derryberry, farmer, 37, $862, b. TN, Lucretia Derryberry, 38, b. TN, Isaac Derryberry, 14, Nancy Derryberry, 12, Virginia Derryberry, 11, Carolina Derryberry, 9, Calvin Derryberry, 7, William Derryberry 5, Gilbert Derryberry, 4, and John Derryberry, 1, all children b. MS except for John, b. Arkansas.

[47] 1870 U.S. census, Little River Co., AR, Henderson Derryberry, 45, b. TN, Lucretia Derryberry, 44, b. MS, Isaac Derryberry, 26, Catherine Derryberry, 24, Andelina Derryberry, 23, Caroline Derryberry, 20, Scott Derryberry, 19, Anderson Derryberry, 14, and John Derryberry, 12, all children b. MS except for John, b. AR.

[48] 1880 U.S. census, Little River, H. D. B. Derryberry, 58, b. TN, wife Lucresa Derryberry, 59, b. TN, and granddaughter Martha Derryberry, b. AR, father b. TN, mother b. MO.

[49] Pauline S. Murrie, Marriage Records of Nacogdoches County, Texas 1824-1881 (1968).

[50] Nacogdoches Co. Deed Book W: 505, FHL Film 1,003,601, deed dated 15 Apr 1872 from Ava Ann Estes to William Parish, all her right to a tract of land known as the estate of David Parish dec’d. Signed Ava Ann and John Estes.

[51] Carolyn Reeves Ericson, 1854 School Census of Nacogdoches County. The U.S. census records are inconsistent: the 1860 census says he was born in Alabama, the 1870 census says Mississippi.

[52] Tishomingo Deed Book Q: 305, FHL Film 0,895,878.

[53] 1870 U.S. census, Nacogdoches Co., TX, household of John Esthers, sic, 48, with Ann Estes, 50, Nancy Estes, 11, and William Somers, 20; 1880 U.S. census, household of her brother David Parrish, Avy Ann Esthes, [sic] 59, and Nancy A. Esthes, 19.

[54] Cockran, History of Old Tishomingo County, says that Henderson Estes was a Captain in the 11th MS Cavalry, Co. A, and that Toney Estes was 1st Lieut. That is consistent with their military records from the National Archives. Allen W. was originally a Sergeant, but had been promoted to Captain by the time he fought at the Battle of Ezra Church.

[55] Barnes, Marriages of Old Tishomingo County, Mississippi.

[56] Alcorn Co., MS Deed Book 4: 473, original of deed book viewed at the county courthouse in Corinth.

[57] Alcorn Co., MS Deed Book 8: 29, original of deed book viewed at the county courthouse in Corinth.

[58] McLennan Co., TX Probate Packet #2757, original viewed at the county clerk’s office in Waco.

[59] 1850 U.S. census, Tishomingo Co., E. Byers, 24, farmer, b. AL, Alsadonia [sic, Alsadora] Byers, 20, b. MS, Mary Byers, 4, b. MS, Francis Byers, 2, b. MS, Joseph Byers, 2 months, b. MS.

[60] Tishomingo Deed Book H: 417, FHL Film 0,895,875.

[61] Tishomingo Deed Book Q: 307, FHL Film 0,895,878.

[62] Tishomingo Deed Book 2: 590, FHL Film 0,895,389.